Mom. 1941, Autumn

*

when they shot my grandma aunt and three cousins

refugees from their town whispered the news to my mom

I was eleven and a half years old –

and could lip-read Yiddish well

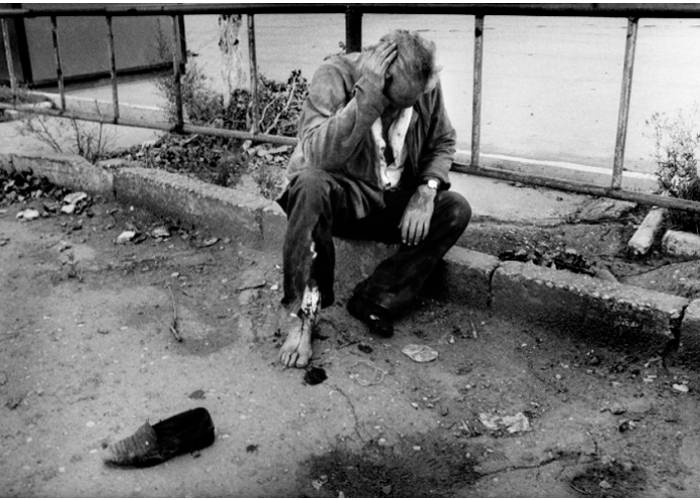

I screamed – but mom said be quiet there’s no time to scream

the nazis were following hot on the refugees’ heels

my mom led me my brother and three female cousins outside

(they’d managed to send the girls here with the first wave of refugees)

and took us to the station

a steam engine was wheezing – and there was still space to squeeze into the freight wagons

she said wait and ran back home to fetch warm clothes

suddenly bombs started dropping my brother yelled lie down but sat up himself

my one-year old little sister was asleep in his arms

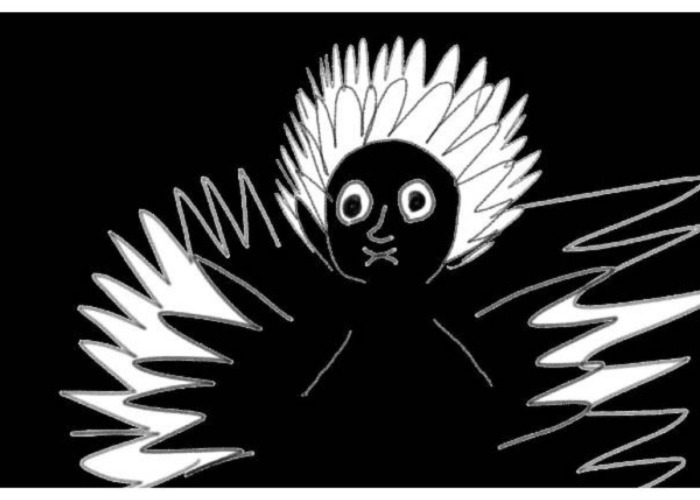

the sky was coughing like a sore throat – just very loudly

I thought the sky’s in pain looked up and couldn’t see the sky

a wound sealed by a membrane of pus split open

a bomb fell on our house I screamed again but my brother said

be quiet be quiet mom is coming

he was older than us girls but he was crying too

mom came back without the clothes –

she’d fallen near out house and couldn’t get up straight away

and now she was limping but: alive! alive!

we squeezed into the freight wagon and warmed ourselves against human bodies

we were standing and whenever we fell asleep we’d fall onto people we didn’t know and they on us

the steam engine didn’t stop we were moving away from the war

travelling through the war for this entire long night

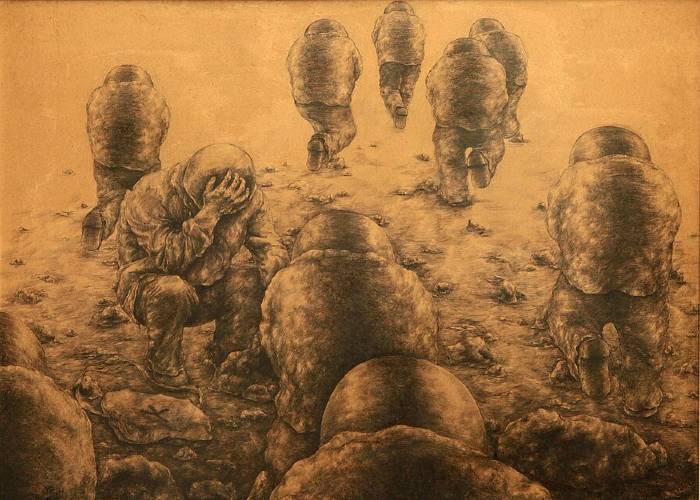

at one of the stations people jumped down from the freight wagons

they passed children who’d died from hand to hand put them on the ground while they dug a pit

at that point none of us was dead yet –

only my little sister wouldn’t wake up it seemed she was tired of seeing and hearing

they told my mom: the local town is twenty kilometres from here

there’s a hospital there

mom took my little sister and set off

I gazed after her I saw how she was limping how walking was painful for her

but she stepped on the pain one step after the other she overstepped it for the sake of the small life in her arms

while we were left to wait on the bench by the station

*

son have you ever tried words for their taste and look

it was then on that bench that I first saw words

they turned out to be slippery iron spheres

hardly knocking against each other

but perhaps once I’d seen words I stopped being able to hear them

the hardest and most slippery one was “challah”

although challah is soft my mom would bake challah only for Rosh-Hashanah

and challah was in my mom’s voice

when she’d call for me and my brother to come inside and the table was laid

we would break off bits of challah dunk it into our broth and eat it

and now I was using my tongue to roll challah and other words along my lips

they kept falling into the cracks rolling onto my tongue and into my throat

but didn’t reach my voice

my throat hurt from the iron spheres but then almost stopped hurting

it whimpered strangely – perhaps because my voiced had gone into hiding

and my throat was calling it

we sat on that bench for four days / four nights

and if someone had had a concern for us

they might have thought we were crying but we hardly cried at all

our faces were wet – everything was wet

from the lymph dripping down from above

(the wound above the trees and roofs could no longer skin over)

on the fifth day mum came back alone

my little sister had died in hospital they’d buried her

mom’s leg was no longer limping

it had become huge and she was dragging it

we helped mom to get into the freight wagon

the people in there yelled faster faster

the steam engine was hissing again the wagons lurched forward

we were hanging on to the doors some women dragged us inside

whether it was another steam engine or the same

I no longer remember

*

grandma

when I finally dared to ask

how she had been living before I was born?

she called the Civil War her first death

and WWII her second

in 1919 she turned thirteen

her life consisted of games reading prayers

with them: her older brother Zhenya and her younger sister Bella

the young century was playing praying and reading

…

grandma didn’t know what faction this gang represented –

the locals called them after their chieftain

this wasn’t a Jewish pogrom

the bandits chose the houses of wealthy Jews

killed everyone they came across

carried away everything they could carry away

the family hid in the basement –

and the century slipped away

and when the front door slammed shut Zhenya risked coming out

the house was empty

voices growing fainter wafted in and Zhenya opened the window

one bandit was trailing behind – the content of his sack was tumbling out –

he stuffed the silver knives plates forks back in

… turned around and fired a shot…

the bullet hit Zhenya in the throat

grandma used to say

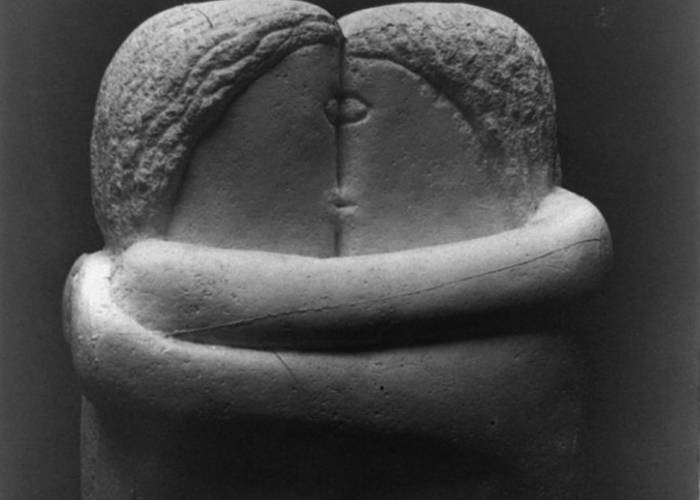

death is living inside us but hiding away in embarrassment

and when it picks up courage – it embraces us and leads us away

back then I managed to get a good glimpse of it –

and death remained next to the open window

glancing mournfully trembling with fear not knowing what to do now

I often approached the window Zhenya’s calm gaze lingered there

I looked through it at death and thought I knew everything about it

but when the second war came

and the nazis shot my mum Bella and her three sons

I understood that I had been mistaken

there is no onwards

I saw: death was no longer trembling with fear

it turned away from me

… grandma died one warm autumn at the close of the century

on a hospital cardiology ward

when she saw me she whispered:

the century is also saying farewell you’ll stay behind and it’ll leave

it’s had enough

Bella came and left in it

it’s the same age as Zhenya

while death says – it’s been too long

death is by the window as always and wants to embrace me

will you let me go?

The Originals

Мама. Осень 1941 года

*

когда мою бабушку тетю и трёх двоюродных братьев расстреляли

беженцы из их города шёпотом рассказали об этом маме

мне было одиннадцать с половиной —

и я хорошо понимала идиш даже по губам

закричала — а мама сказала замолчи некогда кричать

вслед за беженцами шли нацисты

мама вывела из дома меня брата и трёх двоюродных сестёр

(их успели отправить с первыми беженцами)

и отвела к станции

там хрипел паровоз— и в теплушки ещё можно было втиснуться

сказала ждите и побежала домой за тёплыми вещами

внезапно началась бомбёжка брат крикнул ложитесь а сам сел —

у него на руках спала младшая годовалая сестрёнка

небо кашляло как больное горло — только очень громко

я подумала небу больно посмотрела вверх и не увидела неба

рана затянутая пленкой гноя лопнула

бомба попала в наш дом я снова закричала а брат сказал

замолчи замолчи мама придет

он был старше нас девчонок а сам тоже плакал

мама вернулась без вещей —

упала около дома и не смогла сразу встать

и теперь хромала но: жива! жива!

мы втиснулись в теплушку грелись людскими телами

стояли а когда засыпали падали на незнакомых людей а они— на нас

паровоз не останавливался мы уезжали от войны

ехали по войне всю эту очень долгую ночь

на одной из станций люди прыгали из теплушек

умерших детей передавали из рук в руки складывали на землю пока рыли яму

из нас тогда ещё никто не умер —

только маленькая не просыпалась казалось ей расхотелось видеть и слышать

маме сказали: до райцентра километров двадцать —

там есть больница

мама взяла сестрёнку и пошла

я смотрела ей вслед видела как она хромала как ей больно идти

но шаг за шагом она наступала на боль переступала ради маленькой жизни в руках

а мы остались ждать на лавочке у станции

*

сынок ты когда-нибудь пробовал слова на вкус и взгляд

именно тогда на лавочке я увидела слова

они оказались скользкими железными шариками

почти не бившимися друг о друга

а может увидев слова я разучилась их слышать

самым твёрдым и скользким было «хала»

хотя хала мягкая мама пекла халу только на Рош ха-Шана

и хала осталась в мамином голосе

когда она звала меня с братом со двора и дома был накрыт стол

мы отламывали кусочки халы макали в бульон и ели

а сейчас я катала халу языком по губам вместе с другими словами

они падали в трещинки скатывались на язык и в горло

но до голоса не доставали

горло болело от железных шариков а потом почти перестало

как-то странно ныло — может быть от того что голос спрятался

и горло звало его

мы сидели на лавочке четверо дней | четверо ночей

и если бы кому-то было до нас дело

он мог подумать что мы плачем но мы почти не плакали

лица были мокрыми— всё было мокрым

от сукровицы сочившейся сверху

(рана над деревьями и крышами уже не могла затянуться)

на пятый день мама вернулась одна

сестрёнка умерла в больнице ее похоронили

нога у мамы больше не хромала

она стала большой и волоклась следом

мы помогли маме забратьсяв теплушку

оттуда кричали быстрее быстрее

паровоз снова хрипел вагоны дёргались

мы повисли на дверях нас втащили какие-то женщины

другой это был паровоз или тот же самый

уже не помню

*

бабушка

когда я решался спросить

как она жила до моего рождения?

она назвала Гражданскую войну первой смертью

а Вторую мировую — второй

в девятнадцатом ей исполнилось тринадцать

жизнь состояла из игр чтения молитв

с ними: старшим Женей и младшей Беллой

юный век играл молился и читал

…

какого цвета была эта банда — бабушка не знала

местные называли их по фамилии главаря

это не было еврейским погромом

бандиты выбирали дом зажиточных евреев

убивали всех кто встретился на пути

уносили всё что могли унести

семья скрылась в подвале —

и век ускользнул

а когда хлопнула входная дверь Женя рискнул выйти

дом был пуст

с улицы доносились затихающие голоса и Женя открыл окно

один бандит отстал— из мешка высыпалось содержимое —

запихивал серебряные ножи блюда вилки

…оглянулся и выстрелил…

пуля попала в горло

бабушка говорила

в нас живёт смерть но прячется в стеснении

а когда осмелеет — обнимает и уводит с собой

тогда я успела её рассмотреть —

и смерть осталась возле открытого окна

смотрела жалобно дрожала от страха не понимая что дальше

я часто подходила к окну там оставался Женин спокойный взгляд

смотрела сквозь него на смерть думала что всё о ней знаю

а когда пришла вторая война

и нацисты расстреляли маму Беллу и её троих сыновей

я поняла что ошибалась

нет никакого дальше

я увидела: смерть больше не дрожит от страха

она отвернулась от меня

…бабушка умерла тёплой осенью в конце века

в больничной палате инфарктников

увидев меня шепнула:

век тоже провожает ты останешься а он уйдёт —

устал

Белла пришла и ушла в нём

он— ровесник Жени

а она — заждались

она как всегда у окна хочет обнять

отпустишь?