Wooden horses

Gallop, kicking up dust…

–Boris Pasternak

The carousel was set up for the May holidays. It was installed in the park behind the club, opposite Khemka’s shoe repair shop. It was brought in pieces on a tractor from the flax factory, where it had been stored all winter.

In Khemka’s family, all the men were shoemakers: his grandfather, his father, and his great-grandfather. As Khemka’s father, Nokhem, said:

“Our great-grandfather, Reb Zussl, made boots for Peter the Great himself. And he was a picky customer. If something weren’t right, he’d put you on the rack! And his grandson, Reb Esl, worked for Bati himself. He was such a shoemaker: his shoes were famous all over the world!

After tenth grade, Nokhem took Khemka to the director of the House of Crafts and said:

“That’s it, I’m retiring. I’ve done my time. Now let Khemka be a shoemaker.”

“All right,” said Vasily Vasilyevich, knowing that shoemaking was a delicate business and that there were no other shoemakers in Krasnopolye except Nokhem and his family.

And Khemka took up his new position. He was as good a craftsman as his father, if not better, because unlike old Nokhem, who always made the same thing, he tried to learn how to make everything like the stuff he saw in shops or in the magazines his German teacher let him look at, after he had once sewn boots for gnomes at school, which were then taken to all the exhibitions in the school and district. That’s how he learned to sew women’s boots. He bought Austrian boots in a store, took them apart, made patterns, racked his brains over them, and sewed boots that took the breath away of the very first fashionistas in Krasnopolye. Nokhem scrutinized his son’s work and spread his arms: there was nothing to complain about!

Khemka sewed his first pair of boots for Katya, the daughter of the dairy factory’s director, Meer Haimovich. Rimma Zalmovna came to have her heels repaired, and Khemka showed her his boots. She gasped at the beauty and, of course, immediately asked if she could order boots like these for Katya.

“Take these,” said Khemka. “I think they’ll fit her perfectly.”

“How much are they?” asked Rimma Zalmovna.

“Nothing,” said Khemka.

“What do you mean, nothing?” asked Rimma Zalmovna in surprise.

“Can I give them to my first pioneer leader as a gift?” asked Khemka.

“You can,” agreed Rimma Zalmovna. “But not such an expensive gift!”

“I’m making them for advertising,” said Khemka. “Did you read in ‘Izvestia’ that Americans give away cars for free for advertising? And here it’s just boots! When other girls see Katya’s boots, they’ll be jealous and come running to me to order some! The profit will go to the state!”

“Capitalist!” laughed Rimma Zalmovna.

And she took the boots.

The next day, Katya stopped by Khemka’s on her way to work.

“Thank you!” she said.

“Do they fit?” asked Khemka.

“They fit perfectly,” said Katya. “I put them on as soon as my mother brought them.” She lifted her long skirt slightly to show the boots and, turning around in front of Khemka as if in front of a mirror, added, “I’m advertising them for you! Are you happy?”

“I’m happy!” he said, blushing.

“Thanks, capitalist!” she said, and added, “That’s what my mom called you. She brought me the boots and said they were a gift from the capitalist,” and, smiling, she repeated, “Good luck, capitalist!”

“Wear them well!” said Khemka.

“Today is the opening of the carousel,” Katya added as she left. “Come! I’ll give you a free ride! I can give a gift to my former pioneer!”

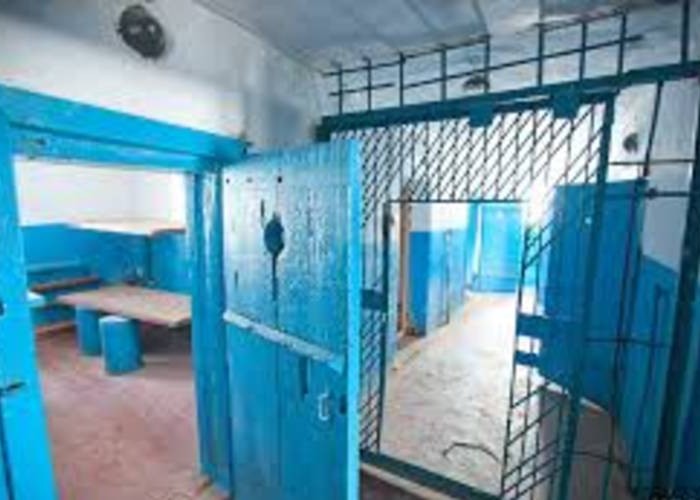

Katya worked as the club manager and was in charge of the carousel, because the motor’s power cord was connected to the club, and the club’s ticket seller sold tickets for the carousel. Two workers from the flax factory spent two days assembling the carousel: on the first day, they assembled the carousel itself, and on the second day, they built a fence around it. And then came the solemn moment of the opening. Before letting the first visitors on, Katya herself would sit on one of the wooden horses and do a lap of honor. Khemka waited all year for these moments. He would sit right by the fence and stare at Katya without taking his eyes off her. She would sit on the wooden horse as if it were a real horse, sitting sideways, “like a noble lady,” as they said in Krasnopolye, and ride around in circles, blowing kisses to the crowd surrounding the carousel. She loved the carousel. And Khemka, too, loved the carousel. And he loved Katya. He had loved her since school. From the moment she came into their class as their pioneer leader.

“She’s beautiful!” he said to his deskmate, Romka Kuryushkin.

“She’s ordinary,” Romka replied and added in a grown-up tone, “Like all women!”

“Not like all women,” Khemka objected. “She’s extraordinary. Like a fairytale princess.”

“You found a princess!” Romka grumbled. “She gobbles up cream in the morning, that’s why she’s so rosy.”

He wanted to say something else, but Khemka showed him his fist, and he fell silent.

Katya was five years older than Khemka. For Krasnopolye, that was a big difference, an impossible difference. And so Katya looked down at him the way a Komsomol member looks down at a young pioneer, exchanging two or three words with him when they met, as she did with all her younger acquaintances, and Khemka loved her secretly, silently, sharing his secret with no one. Katya looked for a husband among her peers.

And perhaps she would never have known about Khemka’s love if Jewish life in Krasnopolye had not suddenly changed dramatically: Jews began to leave, some for Israel, some for America, some for Germany. As the madman Zelik said,

“Open the gates—all the gentlemen are leaving!”

One of the first to start packing was Meer Khaimovich. Khemka learned of his leaving from the Community Center’s director.

Vasily Vasilyevich stopped by his workshop at the end of the day. He sat down silently in the customer chair and stared at Khemka.

“Vasily Vasilyevich,” asked Khemka, “did you come to have your shoes repaired?”

“No,” said Vasily Vasilyevich, and, looking questioningly at Khemka, asked, “Are you leaving?”

“Where?” Khemka did not understand.

“To America,” said Vasily Vasilyevich.

“Me? To America?” Khemka was surprised. “What would I do there?”

“Come on,” said Vasily Vasilyevich. “Don’t play dumb! Who else but a capitalist would go there? You’ll open a shoe factory! All of you are getting ready to leave, some sooner, some later. Even Meer Semyonovich is getting ready!”

“And Katya?” asked Khemka.

“They’re leaving, too,” said Vasily Vasilyevich. “Yesterday, at the district committee office, they expelled Meer Semyonovich from the party and removed him from his position. And Katerina Meerovna is quitting her job.”

“And who will be the director of the club?” asked Khemka, without even not knowing why.

“Does that matter to you?” snorted Vasily Vasilyevich. “They’ll find someone. There are plenty of directors. Pick anyone, and they’ll be a director. But if you leave, I won’t find another shoemaker! That’s why I’m asking. If you decide to go, let me know in advance. It takes six months to find a specialist at the regional administration! Agreed?

“Agreed,” said Khemka.

That same evening, Khemka brought up America with his father.

“We don’t have anyone in America,” said Nokhem. “In fact, we don’t have anyone anywhere. Where would we go? It’s good where we are, and it’s all the same where we go! As my mother used to say, ‘A pocket full of holes is empty everywhere!

Khemka lay awake all night thinking about his father’s words, about Katya, about himself…

Every morning, Katya walked past his workshop on her way to work. He always stood in the doorway and said to her:

“Hello!”

And she would say to him as she passed by:

“Hello!” and walk on.

But that morning he asked:

“Are you leaving?”

“Yes,” she said and stopped.

“Do you think it’s better there?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” she said and added, “I’ll be twenty-one soon, and I don’t have a fiancé. All the Jewish guys will soon leave Krasnopolye, and I’ll be left an old maid. And there are a lot of Jews in New York. More than in Israel!”

“More than that?” Khemka was surprised.

“That’s what Aunt Hasya writes,” said Katya.

“I’m staying,” said Khemka. “We have no one else!”

“Oh, I feel sorry for you, pioneer!” said Katya. “Where will you find a Jewish girl then?”

She looked at Khemka intently and said thoughtfully:

“Marry the one who’s leaving right now! And go with them!”

“Then marry me,” Khemka said unexpectedly. “And I’ll go with you!”

“Oh,” laughed Katya, thinking he was joking, “I’m too old for you! They’ll laugh at us in Krasnopolye! I remember my literature teacher saying that Leo Tolstoy’s mother was five years older than his father, and the whole class laughed as if she had said something indecent.”

“But they had Leo Tolstoy,” said Khemka and blushed.

Katya looked at him in confusion, and Khemka, emboldened, added:

“I love you! I have for a long time. Since I was in fifth grade and you were in tenth. Since when you were our pioneer leader.”

“But I’m older than you!” Katya said, confused. “And my aunt found me a fiancé in New York! There are plenty of people your age around here! Do you want me to introduce you to Aunt Perla’s daughter? They’re leaving in two years, waiting for Dora to finish technical school. Dora is a pretty girl!”

“No, thanks,” said Khemka.

“Or would you like me to introduce you to Rivka Khasina?” said Katya.

“No, thanks,” repeated Khemka. “I love you!”

“Silly boy!” said Katya. “You’re so silly! Not everything in life turns out the way we want it to! You have to accept things as they are. “ That’s what your Leo Tolstoy said, by the way,” Katya sighed and added, “I was also in love with my gym teacher once.” So what? It’s all over now. It was just a childhood crush. It will pass for you, too! Forget me. Is that agreed?”

Khemka didn’t answer. And from that day on, Katya stopped walking past his workshop.

She left in late autumn, on the day when the carousel was being dismantled. Khemka felt that she would come to the carousel. He waited for her.

A drizzle was falling. The workers, Avdey and Nikolai, were cursing their bosses for sending them to dismantle the carousel on that day, as if they couldn’t wait for a sunny day.

She came up behind him unexpectedly and covered his eyes with her hands.

“Katya!” he recognized her immediately.

“I thought you wouldn’t recognize me,” she said and added, “I came to say goodbye to you and the carousel. We’re leaving today.”

“I know,” said Khemka.

“You never wanted me to introduce you to anyone.”

“I didn’t want you to!” he said.

“You know,” she said, “I’ll miss you and the carousel there.”

“There will be a carousel!” Khemka said confidently. “There are carousels there, too.”

“But you won’t be there,” said Katya.

“What do you need me for there?” said Khemka.

“Who will sew my boots?” asked Katya.

“Clinton!” he said.

Katya smiled. But the smile seemed forced, because sadness lingered in her eyes.

“Good luck, capitalist!”

“Good luck to you, too!” said Khemka.

“Goodbye!” said Katya and squeezed his hand. “Don’t be mad at me! Okay?”

“Okay!” said Khemka and bit his lip.

And she left.

Khemka remained standing.

“Where are they going?” asked Avdey. “To Israel?”

“To America,” said Khemka.

“America is good,” said Nikolai. “If they let us go, I’d go too.”

“Wait and see—they’ll let you go!” snorted Avdey.

“Why aren’t you going?” asked Nikolai. “Shoemakers are needed everywhere!”

Khemka didn’t answer.

…He was almost the last to leave Krasnopolye six years after the Haimovitch family. He went to Germany. He settled in a small town near Cologne. He opened a shoemaker’s workshop near the park. Not far from the city carousel.

In the morning, on his way to work, he always takes the long way, through the park, past the carousel. At that time of day, the carousel isn’t running yet. Khemka stops near it. He stands there, leaning against the fence, and looks at the wooden horses. For a long, long time. Until the carousel begins to come to life before his eyes, the wooden horses start to wave their rope manes, spin their huge plastic eyes, and sing “Lorelei” in German:

“I don’t know what has come over me,

My soul is filled with sadness…”

And as if out of thin air, Katya appears. She is wearing a light summer dress and high-heeled boots. She jumps onto a galloping horse and blows a kiss…