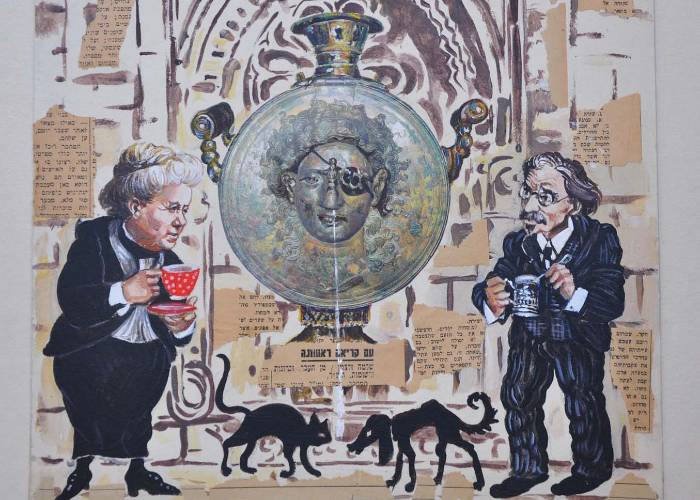

It was so long ago that there was no Sphinx yet. And there was no moon either. And the games they played were dominoes and “king peas”. They would hide a pea in the dough, bake a loaf and treat a passer-by with it, and to whomever a loaf piece with a pea would fall out, they would dress him up in brocade, put a paper crown on him, and call him a pea tsar. And they would dance around him. That’s how long ago it was. That’s why we say in Russian: “in the time of the tsar-pea.”

Once upon a time, there lived a rich oil industrialist. Is there such a thing as a poor oil industrialist? He traded in paper, shares, wood, and derivatives. And he owned newspapers and bribed paper journalists. But words, those boogers, which would dance to the industrial tune, if that’s what was wanted of them, or sit in a box or belong only to him, pierced by a needle – he had nothing like that. So he went to the Regulatory Chamber. And he said, Give me a handful of verbal ore, so I can own a certain amount on an individual basis. And so that no one else would have any opportunity to touch them. And they say to him: pay this amount, sign here, and own it whenever you want. The industrialist liked this: let’s say a person is walking, talking on the phone or with a neighbor, and he wants, you know, to say an ordinary word, and suddenly his tongue slips. Or, say, you want to write an ordinary word – and just then your hand slips. Clearly, it means that there is no possibility to write or pronounce the word, only mentally. You can read the word silently, but only if it has been printed. Main thing, you can’t say or write it yourself. All you’d get would be a slippery gap.

The industrialist took a few more handfuls of words, as many as would fit in his pockets, and then he grabbed the whole dictionary. He blabbered until the air ran out in his throat, while no one else said a word. And he made the journalists write books with the words he had bought, to supply the people with them. That’s how he got hold of the Word! Everybody would dance to his tune now. What could they do? If they wanted to say something, they had to take out the industrialist’s phrasebook and point at it: “Sell me some water or bread.” That was how, at first, we went around with phrase books. And the industrialist made even more money from this than from oil and derivatives.

It must be said that there were just stumps left from words that remained in public use, the nibbled-out bones of the language, so to speak. And not everyone was amused with this situation. And so people began to look for ways out. At first, they started to speak with gestures, then they made up words that were like sunflower seeds and started spitting them out. Some talked backwards, some mixed up the syllables, some twisted the sounds in ways so impossible that no one could understand them. You walked by and wondered at what you heard: zoo sprechen sprach geschprochen!

Historical linguistics later managed to count fifty local and group anti-censorship dialects. Everyone spoke in their own way, mooing or bleating. It became fashionable to have special jabberias – special talk shows where you had to out-babble everyone else in a language improvised on the spot.

But that was just the beginning. Social bonds began to break down within a week of the success of the jabberias. No one wanted to listen to or understand the other. Everyone spoke by themselves. People were selling their last reference books, phrasebooks, and all their remaining paper literature in order to buy the last remnants of bread and clothing. A furry Discord ran through society, as recorded later by the historical science. Many homemade and unmade languages were practiced. There appeared a multitude of small groups that neither understood each other nor interacted in any way but always warred over the last unplundered means of production. Everywhere one could hear squabbles, localized wars, and conflicts. Factories came to a standstill, warehouses were dismantled, lands were abandoned. Cities and villages were plunged into darkness. The bonds of time broke down, and the Tower of Babel fell from the heavens, with all its rattling bricks. As a historian bitterly remarked in a lyrical digression, a society without a common language is nothing but the ruins of the Tower of Babel.

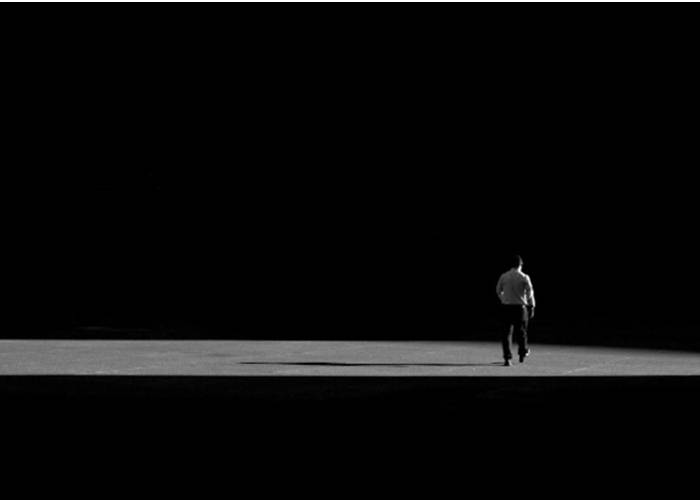

In addition to the fact that few people could understand anything, there began to be widespread madness, because people could no longer think coherently and voluminously. The last conscious individuals still shone like candles in the night to unite the degenerating crowd around them.

The industrialist himself came down in the world and was like everyone else. The last thing he could remember was running to the Regulatory Chamber to waive his linguistic rights and claims, but it was too late, everyone had lost their speech hearing, the original language seemed too complex, alien, and hostile to the petty bureaucrat at the registration table.

And so, notes the historian, the nation perished in ignorance and madness….

But at this very time, a hermit poet was safely finishing his next poem. For two and a half months he hadn’t left the house or turned on the TV or read his Friendlenta*. Now that the final point had been reached, he hopped off to the store for wine. And what doid he see? Feral, wordless creatures roaming the streets, only their upright posture and ineradicable habit of standing in line looked human. Well, well, the poet turned to one of them, who still had his pants on, and can you tell me what this is all about? The citizen recoiled from him and fled in terror. And then he came back with a mute, hungry crowd. Aha, the poet realized, that’s what this was all about! The language had been lost. The inspiration had been lost. The fragile inner microcosm was destroyed. That’s what my last poem is about. So, Prometheus, let’s roll up our sleeves and start building a new world.

And the poet gathered the people and seated them in a circle in front of him. He gave them lectures on versification and eloquence; he quoted by heart the best monologues of mankind, passages from Shakespeare and Proust, songs from Homer, excerpts from “Primary Chronicle,”** and, of course, the most favorite and successful lines of his own composition. But only tiny bits of it. It was an unheard-of, unprecedented opportunity: to give people the gift of a new era, illuminated by a pure, powerful, sonorous Word, which would descend not on some faraway tribes such as the Englishmen or the natives of Madagascar, but on the tribe of Pushkin and Pasternak lovers, inheritors of Brodsky and worshippers of Nabokov! How glorious this coming epoch would be, the poet dreamed.

In the evening, when people sitting at the feet of the self-proclaimed teacher began to be bored with chanting in rhyme, addressing the right half-chorus and the left half-chorus with songs, learning tongue twisters, proverbs, Bouts-Rimés, composing free verse, hexameters, choriambuses, or dactylic polysyllabic pseudo-anapesthestic meters, they scratched their armpits and went back to their dens and caves.

It seemed that this was it: humanity was finished! The labors of millions of years lay buried under the volcanic ashes of phrases like “We are lazy and uncurious,” under the carpet of fleeting butterflies of sleep, luring people to lose awareness in a far corner of a cave…

But on the following Monday, a deputy walked by, feeling neither sad nor happy. He had returned from a Swiss vacation and was about to start the fall session. Having discovered the deplorable state of affairs and having looked through his fingers at the amateurish projects of the poet, he instantly built his own support group out of the downcast electorate, organized a party of national unity, a guild for the protection of human rights from people, a movement to defend the motherland, and another one, to defend the motherland from everything else. He spoke pleasantly and confidently. He answered silent questions before they were even spoken and he knew how to read the souls of men. He promised everything, because no one could write down his promises anyway. The audience applauded him unanimously.

A month later, everything was back to normal. And everything was even more wonderful than before. Words were issued on special cards and read out on holidays. And no one could think of anything else but those words. Everyone was happy. And the hermit poet crawled into his den to compose a new poem, this time quite postmodern, composed of different genres, styles, languages and layered chronotopes: a true ocean poem.

So much for Wittgenstein.

_______________

* Friendlenta – mixture of English (“friend”) and Russian (“lenta”/”лентa” – literally, “ribbon,” here “lenta” is used to mean “news feed”).

** “Primary Chronicle” – The Russian Primary Chronicle, commonly transcribed Povest’ vremennykh let (lit. ’Tale of Bygone Years’), is a chronicle of Kievan Rus’ from about 850 to 1110. It is believed to have been originally compiled in or around Kiev in the 1110s, and was traditionally ascribed to the monk Nestor.