If you please! Why not have a cup of tea? A nice cuppa, as Britons used to say! On a train without tea, Mr. Sholem Aleichem, if I may say so, you feel like a stranger in a far-off land…

Speaking of tea. Please don’t look at mе, so good-looking and well-nourished, as if all my life I’ve only been traveling from Zhytomyr to Berdichev and getting off a train only to buy a bun in а station buffet. Let me tell you, there were in my life one or two distant trips…

Excuse me, where did we start? Oh yes, tea! Believe me, no matter what this learned gentleman, Reb Usher Gintsberg, who writes for us his addicated articles under the name or, to put it in a new, scientific way, under the pseldonym “Ahad Ha-Am”, and prints them on the money of the late Reb Wolf-Kalman Vysotsky in his most respected paper “Ha-Shiloach”, no matter what he says, one will not live on spiritual food alone. Of course, the Holy One, blessed be He, poured on our long-suffering people, on Jews, Hebrews, and even, if I may say so, on sons of Israel, manna from heaven, but… But our time is progressive and up-to-dative, now a modest person cannot rely on such lovely miracles. Therefore, from my youth I was greatly worried over the considerations of the Lovers of Zion, that it would not be bad for us to sow and plow (or first plow, and then sow – who can be sure!) on the Land of the Fathers, instead of spoiling our eyesight over books and needlework among cockroaches, somewhere in Shpikov, or, God forbid, in Baranovichi…

This was even before Dr. Herzl’s time with his Basel compress. Today every smart person considers himself a Zionist, that is, can clear his conscience in face of his oppressed people’s cries and groans with two rubles contributed to the Land Fund. Mind you, I’m telling you about the time when this propress was still far away. However, such a penspicacious and consciencious man as Reb Wolf-Kalman was already able to foresee all this cybilization and draw proper conclusions. I’m talking of the eighty-fifth year of the last century, the rule of Emperor Alexander III. I was just starting to earn my own living and was sent from my native Gomel to him (no, not to the emperor, but to Vysotsky) in Moscow, to buy goods. This time I won’t describe Moscow to you (it won’t run away from its place, as they say), I’ll get straight to the point.

Wolf Yankelevich received me personally, an honor, which, I must admit, I could not even imagine in my wildest dreams. He looked at me with his vigilant outlook and said:

“You,” he says, “Reb Nochum…”

It’s me – Reb Nochum! Still, a youngster, the milk on my lips, as the saying goes, has not dried up – and he says to me: “Reb Nochum”!

“You,” he says, “Reb Nochum, seem to me a person suitable for my plan. Would you like to accompany me on a trip to Eretz Yisroel?”

Why should I waste your precious time and, if I may say so, get on your nerves… To make it short, he, the great millionaire, achieved for us the necessary documents (all the policemen in Moscow bowed to him down to the earth and called him “Vasily Yakovlevich”), and two months later we set foot on the Holy Soil of the Holy Land.

And so… If you think that in those days the Holy Land was the Holy Land, then I’m glad for you! A quarter of a century ago, it looked more like a big smelly dump in Berdichev in the middle of the summer – stink, flies, and, let this not be said of us, all sorts of decorposition of matter, as the learned gentlemen put it. Wherever we’ve been – in Gaza, where Samson bashed the Philistines, in Shechem, where the sons of Jacob circumcised the Canaanites – everywhere, the Turks with their bazookas and the Arabs with their hookahs. But I was going to tell you about what happened in Jerusalem.

In Jerusalem, we settled in some filthy inn. In the afternoon, Reb Wolf-Kalman went with some Lovers of Zion to the Mount of Olives to visit the graves, and I was so exhausted from the heat that I stayed in my room and dozed off. In the evening, we were invited to a reception at the home of Weingarten, a local deep pocket and the synagogue warden. Reb Wolf-Kalman ordered me to take with me one of those batches of tea that he had brought from Moscow.

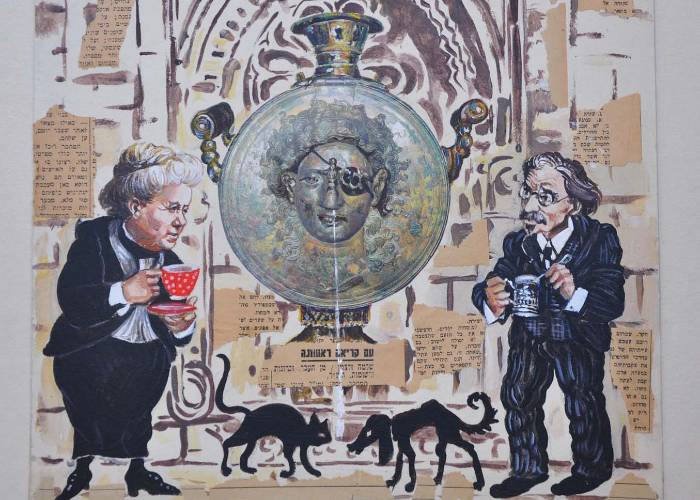

And so, we come to these local moneybags and sit down at a large table. We sit richly, in style, on Viennese chairs, our feet on a Persian carpet, above our bright heads there is a Turkish vaulted ceiling. The people around us are all sons of Israel and Hebrews, not a single Zhyd. What can I say to you, even though the two cramped little rooms of this Weingarten must bow down to earth to the modest two-story Moscow mansion of Wolf Yankelevich (with two staircases – the front one of marble, with columns, and the other one is a bit simpler), everything that this fat cat is proud of is on display. On a crimson tablecloth with Podolsky embroidery stands Batashev’s samovar adorned with medals – a gift from Reb Wolf-Kalman himself. There is also a white-and-gold porcelain sugar bowl with sawn sugar from Avrumke Brodsky, real homemade bagels, lemons from Jaffa, and candied figs from Smyrna… The faces of the entire holy congregation are reverent and even somewhat sycophantic, and two skinny bespectacled Lovers of Zion, former students, not accustomed to such luxury, timidly huddle at the end of the table.

Reb Wolf-Kalman solemnly takes the batch of his best tea from his pocket and raises it above his head. General applause. Everyone is waiting for a weighty word from him, preparing to taste, as the saying goes, the honey of his prudent speech.

“What is tea?” asks Reb Wolf-Kalman.

Respectful silence is his answer. Should they teach Vysotsky himself what tea is?! It’s as if you were to teach me what is, for example, my own, not to be mentioned here, my own unmentionables.

“Tea is, first of all, water,” Reb Wolf-Kalman answers himself. “And what do our prophets and sages, may their memory be blessed, say about water? They say: “If you were worthy, you would sit in Jerusalem and drink the waters of Shiloah, which are pure and sweet waters. Now, when you have proved unworthy, you are banished to the land of Babylon and drink the waters of the Euphrates, which are muddy and stinking waters.”

There is a pond under the city wall, in which Muslims wash their feet. The water in it, they say, is drawn from a stream running underground from the Temple Mount, and, from a medical point of view, has healing and prophyleptic merits. I am not trained in medical sciences, and therefore I will not swear to you that that is true – I only sell it for what I bought it, as the saying goes. Yes, and I didn’t drink this raw water until it was boiled in this very samovar (I am a squeamish person by nature, for me, water becomes water only after it boils in a kettle – whether it came from our Gnilopyatovka or from the spring of Paradise).

“But you, brethren, who have returned to Zion by the grace of the Lord,” continues Reb Wolf-Kalman, “once again are worthy to drink the sweet and pure waters of Shiloah. Here they are, boiling in this samovar!”

And again applause and cheers and the two former students even try to chant the Song of Ascents, but the owner of the house silences them with a menacing look, and again all is stillness and attentiveness.

“These pure and sweet waters are warmed by the flame of our love for Zion,” Reb Wolf-Kalman solemnly continues. “We’ve heated the samovar with these beautiful cones, blessed by God, with fruits of the lofty and mighty pines of the Holy Land. Today, my friends, all the cones were barely enough for this one samovar, but we, with God’s help, will plant hundreds and thousands of pine trees here, and hundreds and thousands of samovars will hum joyfully in the homes of our brothers returned to Zion!”

Once again, cheers and general jubilation.

“Boiling water,” says Reb Wolf-Kalman, “is already half the tea. But there is also a second half, and this second half, my friends, is my concern.” He again raises the batch of his famous tea high above his head. “Now we will make tea, the best tea that our brethren in Zion ever drank. I want these tea leaves and a cup of tea that you will drink now to be remembered for a lifetime. I want this tea to start a new and better life for all our people.”

Here he holds out to our esteemed hostess Mrs. Weingarten his batch of tea and orders her to put six full teaspoons “with a jot” into a large teapot of painted porcelain, placed right there on the top of the samovar.

“Is it really six spoonfuls?” says she in astonishment. “And even with a jot?”

“Exactly. Six with a jot!” confirms Reb Wolf-Kalman. “The main condition for good tea: never spare tea leaves. So command onto your children: do not spare tea leaves, sons of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob!”

“But I don’t dare,” says the hostess, “to brew tea in the presence of Vysotsky himself. I beg you, sir, do it with your own hand!”

“No, no, go on, brew!” Insists Reb Wolf-Kalman. “I trust you.”

So Mrs. Weingarten takes the batch from him. She takes a silver teaspoon. She goes to the samovar and removes the teapot from its top. She puts it on a special small silver plate and removes the lid. Under the lustful gazes of the entire congregation, she cautiously opens the batch of precious tea, plunges a silver teaspoon into it, and looks at its contents with a kind of strange uncertainty. I would even say that the solemn enthusiasm is somewhat cordescending from the biblical features of her face.

“Go on, go on!” repeats Reb Wolf-Kalman impatiently. “Six spoons with a jot.”

The hostess puts into the teapot six teaspoons “with a jot” of the tea. At the same time, she looks like she is burying a close relative. And I think to myself: why is she behaving so strangely, as if she had never seen Vysotsky’s best black leaf tea at six rubles a pound?

Nevertheless, she pours tea into the teapot and pours in it the boiling water from the samovar. She stirs the tea with a silver spoon. At the same time, she looks like she is kneading clay in slavery to the Egyptian pharaoh. She covers it with a lid and puts it back on top of the samovar. She takes a clean linen towel, folds it in half, and covers the teapot with it.

“I see, you are very good at making tea,” Reb Wolf-Kalman smiles. “Very experienced. Now we count to one hundred – and you may pour the tea.”

As we count to one hundred, I watch the holy congregation. Everyone is eager to taste the best tea of Vysotsky.

The first cup, at the sign of Reb Wolf-Kalman, is offered by the hostess to her spouse. Mr. Weingarten loudly and solemnly pronounces the blessing “Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, by Whose word all things came to be”, closes his eyes from the expected pleasure, takes the first sip, and his face changes. His face changes beyond recognition. However, he immediately returns to his relative likeness of God with a joyful and reverent expression and, turning his radiant gaze to Reb Wolf-Kalman, utters only one word:

“Yes-s!”

This “yes” is meant to show that he never, never in all his life, drank anything like this wondrous tea.

The hostess pours the tea from the teapot into cups, topping them up with boiling water from the samovar, and Reb Wolf-Kalman makes signs to her, pointing first to one, then to the other of those sitting at the table. One by one, they say their blessings, take a sip, change their faces, change their faces back, and say “yes” as if they had just experienced the Sinai revelation.

Finally, Reb Wolf-Kalman himself takes the cup from the slightly trembling hands of the hostess, stirs the tea with a spoon, and pronounces the blessing. The whole society reverently replies, “Amen”…

His Adam’s apple trembles under his neat black beard, like Haman before Mordechai, and a spasm runs down his neck… “Our heavenly Father!!!”

“Nochum!” shouts Vysotsky, fiercely rolling his inflamed eyes. ”Nochum! Sheigetz! Tell me, scoundrel, where did you get this batch?!”

I’m ready to be swallowed by the earth. I have never seen Reb Wolf-Kalman like this. My lips are trembling, I can hardly move my tongue…

“When you ordered… to bring… that is… so to speak… a batch of tea, Reb Wolf-Kalman… I took the one that was on your desk…

“Moron! Imp!” He doesn’t look like himself. “This is the holy soil I took from the Mount of Olives! You hear, ganev, this is the holy soil!!! Holy soil!!!”

~ ~ ~

And now, after I’ve told you everything, Mr. Sholem Aleichem, I ask you: can a person in our propressive time follow the path of enlightenment, trusting only ideas and speculations, and not having tried, as the saying goes, everything on the tongue?

You, if you are going to publish this instructive story, please, do take the trouble to add a small endnote, that you heard it with your own ears from a completely trustworthy person and a good family man.

Oh, my tea!!! It’s completely cold now, like a dead body after its tormented soul flew away, let this not be said about us. Well, it doesn’t matter, at the next stop I’ll get us more boiling water from the station…

Self-translated from Russian