All was chaos, that is earth, air, water, and fire were mixed together; and out of that bulk a mass formed—just as cheese is made out of milk—and worms appeared in it, and these were the angels.

— Carlo Ginzburg

Every sleep is a dress rehearsal for the great sleep.

— Irit Katzir

For years I wandered about

In the world

Now I’m going home

To wander there.

—Itzik Manger

He left the hotel at 2:50pm, got change at the liquor store across Collins Avenue, and arrived at the bus stop just in time for the three o’clock bus to Aventura. Several people were waiting in line, and he positioned himself politely at what seemed like the end of it. As was always the case when he traveled, Bruno made sure to assume a visitor’s benign demeanor, deferential to and respectful of the locals. Here, in Miami Beach, he found himself surrounded mostly by Cubans and was more deferential than usual, as if to let them know that even though he was white, in his Jewish heart he was a minority sympathizer.

His Jewish heart. Only a few minutes before, he was lying on his bed, fully clothed, trying to decide what to do with his time now that Mary, whose idea it was to come here, had left and gone back to New York. As he felt himself drifting off to sleep, the thought came to him that, were he to die here, in this anonymous hotel room, the only thing he would regret would be having disappointed Rose, his mother. It was a calm observation, curiously painless and neutral, no doubt because he knew it to be fanciful. There was no need to glamorize his situation: he was stranded, he was left behind, but he was not lost. Indeed, as he liked to tell his students, the real drama often took place not in the visual and tangible, but in the murky domain of one’s idle thoughts. Sometimes they came on angel wings, sometimes not. And then his brain lit up: Aventura! He jumped off the bed, grabbed his jacket, and was out the door.

Now, oddly stimulated and pleased that he had managed a decision and its execution in a ten-minute span, he tapped the shoulder of the man next to him, before allowing himself adequate time to reconsider. The man turned, offering Bruno a broad, open-mouthed smile. Bruno hesitated. The man, still young, was missing his front teeth, which gave him a somewhat mad and roguish look. But, it was too late to turn away, he had to address the man. “The bus to Aventura?” he inquired, and the man, still smiling, said, “Soon, soon, just wait here.”

Poor, and probably Cuban, Bruno guessed. “How long is the ride?” he asked, if only to mask his discomfort, which, he sensed, the man had noticed. “Oh, it’s long, maybe an hour,” said the man, chopping the air above his head as if charting the road ahead.

Bruno nodded, suppressing an urge to rub his palms together as a show of friendliness and goodwill. It was absurd, but all at once he wished for contact, for some confirmation that he existed, that he could still communicate with a fellow human being. He wanted to say more, but found no words to safely express what he felt. The moment passed, and the man turned from him and said something to his companion who responded with what seemed like a lewd gesture and the two of them laughed.

Somewhat annoyed, thinking that he was the target of the joke, Bruno moved a few steps away, busily fishing in his jacket pockets for his sunglasses to protect against the bright, but cold, Floridian sun. He welcomed a brief spark of renewed hope: maybe Aventura, as its name suggested, would turn out to be the right place for him on a day like today. As if to spite, Mary, his shiksa, her face creased with bitterness, made a quick and uninvited appearance, at which time his self-defense mechanism, just as quick, kicked in with the admonition he’d been drilling into his head throughout the morning: For better or for worse, she left. No acrimony. No self-pity.

Yes!—He nearly shook with the need to nod his head and reconfirm his succinct formulation. Earlier in the day, before he had arrived at this mature decision, his mind went spinning in the other direction: I’ve done nothing wrong. Who does she think she is? And why should I put up with her whims? Eventually, though, he regained his cool, for, what was man if not the putative master of his brain? True, he was now agitated again, but he would soon calm himself, just as soon as he found his sunglasses in one of his pockets. Unless he had left them at the hotel, which would mean he would have to go back and fetch them and miss the bus to the wonder-town of Aventura, if it existed.

Here, he found them, thank God for small miracles! He put on the sunglasses, instantly feeling sheltered and aloof. Good. He had decided not to think about her. He had decided to stop settling accounts with her in his head. Now all he had to do was to pull himself together and move on. With time, Mary would be a name relegated to his past, a past populated by others he rarely thought about, people who came to mind fleetingly at distracted moments when he found himself looking back, wondering what had become of so-and-so. Not that he was shutting Mary out. No. He was a forgive-and-forget guy, and were she to make even the slightest gesture, his heart would instantly open to her.

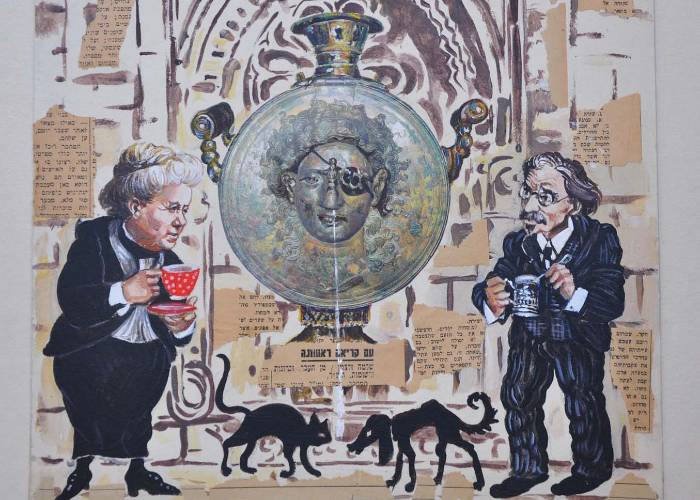

Across the street, a skinny black cat with a white patch between her eyes rubbed her forehead against the pedal of a parked bicycle, and Bruno, charmed, watched her. She seemed peaceful and content, and he wished for himself the same peace and contentment. A simple life, he thought. Devoid of worldly ambitions. Ambition ate at one’s heart and gave nothing back, or, whatever it gave was short-lived. Yes, he had to get himself away from all that was petty and superfluous in his life.

He recalled his father’s tales where cats, especially black ones, often represented demons, and throughout his youth he felt a strong aversion to cats, spitting against the evil eye when a black cat crossed his path. Over the years, though, in the homes of friends, he learned not to fear them, but rather reach a hesitant hand to their wet nostrils. Now, standing at the bus stop, he wondered if the cat, because she was black, was shunned or feared by the other cats. He wondered if, were he in New York, he would take the cat home with him, give her love and shelter.

Yes, he probably would. And she would be a good companion, adding a new dimension to him. He would become softer, more patient, more accepting. Maybe, he thought further, when the bus comes, I won’t get on it. I’ll just stand here and watch the cat. Aventura can wait.

He became aware of an uneasy feeling engulfing him, a feeling of desolation, and a powerful urge to be somewhere else, away from everyone he knew, existing in a kind of Eden where he could live simply, absorbing the tranquility of trees and animals, his heart and mind quiet and content. A bus was approaching and a few people—mostly elderly women laden with plastic bags— rose from the nearby bench, and soon everyone, including those who had stood in line, clustered in a dense group, waiting for the bus doors to open. Bruno, still unsure if he would mount the bus, let them push ahead of him. Besides, he was in no hurry, and the bus was practically empty anyhow. In this godforsaken place, only the poor used public transportation; all the others sped by in their shiny Lexus or BMW.

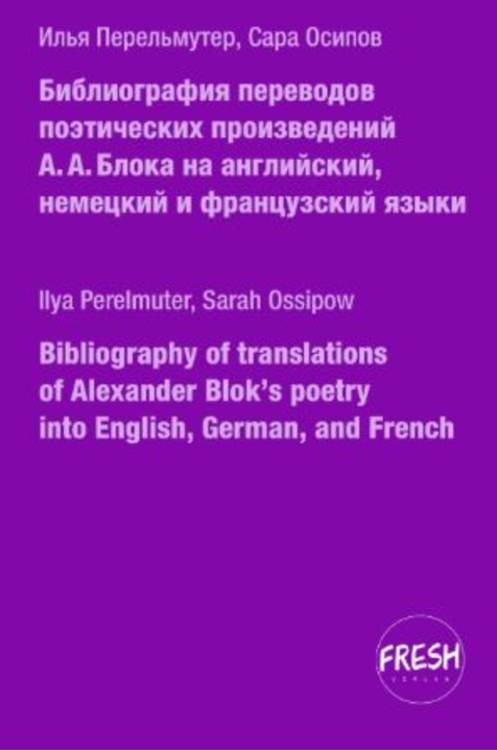

Finally, he did get on the bus, happy to find a window seat that would afford him an ocean view. The longer the ride, he thought, the better. After all, he was a tourist. The day had been too chilly for swimming, and the early-morning walk on the boardwalk—which usually absorbed his thoughts and even got him to hum a random tune—had given him little pleasure. He didn’t see the striking, one-legged woman he saw every morning, but the Hasid women were there, some young, some old, sometimes alone, sometimes in groups of two or three. Quite a few of them pushed strollers with the fierce, preoccupied determination of new mothers. Some of the younger women carried small weights in their hands, which surprised him: he hadn’t known Hasids to be fitness-conscious. More so than the occasional Hasid he saw on the streets of Manhattan, these Miami Beach Hasids, especially the women, looked as though they had been airlifted from a Polish shtetl, and their loud and rapid Yiddish annoyed him, sounding harsh in his ears.

Today’s Ostjuden, he thought. He liked Yiddish, it brought back memories, he liked the idea that Yiddish was kept alive, but he considered it strange and alienating that they chose to speak Yiddish rather than English. He tried not to stare at them, at their long, shapeless skirts, their long-sleeved shirts, their thick, dark stockings, their colorful, yet painfully tight, headscarves. Some of the women had no head covering, and those, he knew, were presumably still virgins, namely unmarried, and therefore not required to cover their hair.

It was a pity they covered themselves from head to toe. Many of them would have been quite attractive if they relinquished their costumes and joined the modern world. In their ungainly outfits, they seemed out of place among the semi-nude joggers, even if the sudden appearance of these exotic turbans and headscarves did make him think of tropical flowers, very much in tune with the dark-green bushes and the old and massive palm trees along the boardwalk. When he first arrived here, a little over a week ago, he looked at them askance, but as the days passed, he found himself offering an open face, hoping to exchange a friendly smile, which he managed once, with a young mother who had bent over the stroller, cooing to her infant and, as he approached, she looked up, giving him a quick, nervous smile, matching the one he had given her.

Interesting that he had to come all the way to Florida to see Hasids on a daily basis. Even the men, not famous for physical activity, took advantage of the boardwalk, and earlier this morning Bruno watched one of them with particular interest: an old, stooped man, possibly a Holocaust survivor, supporting himself with a cane. Large, black earphones covered his ears, and Bruno wondered what kind of music the man was listening to, until it occurred to him that it was probably a rabbi’s sermon, decoding the Torah or the Talmud.

____________________________

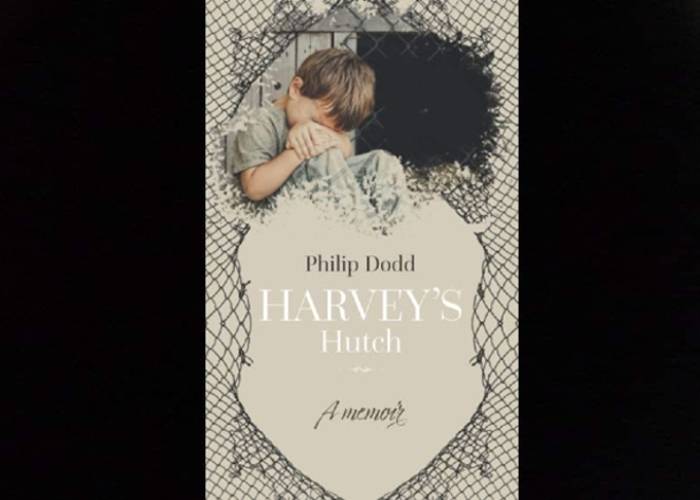

This is an excerpt from Bruno’s Conversion, a novel by Tsipi Keller, published by ITNA Press in 2023.