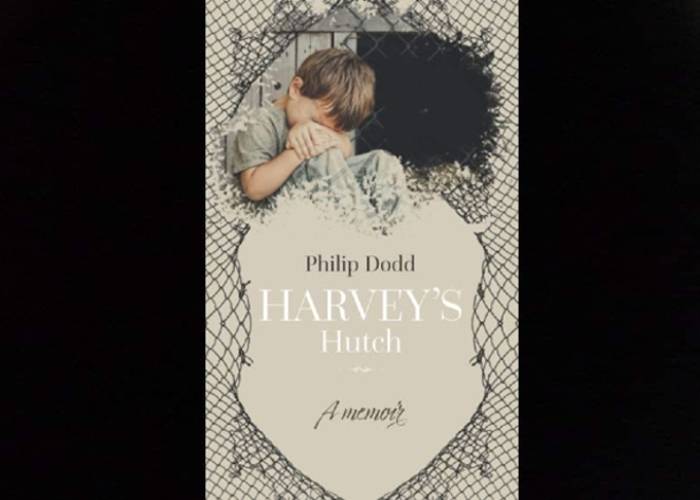

CHAPTER ONE

The Pictures in the Mirrors

My mind creates mirrors in the air. They reveal pictures from my past. The people, structures and objects contained within them look cleansed of any dust or drabness. They appear, therefore, more alive, more compelling, than those I see around me in the present. I have no control over the mirrors. I cannot urge them to be or to vanish. They become solid in the air by their own will, not by mine. It is they that direct this memoir, not my pen.

There I am, in the first mirror, sitting at the kitchen table, having my breakfast. I am a small boy, four years old. My hair lies thinly on my scalp and round my ears. It is fair, almost white. My face is long, narrow, my nose has no shape, my mouth is creased in an almost-smile, and my eyes are blue. I look the same as I do in the black and white snaps my parents took of me at that time. I am wearing a white T-shirt, light brown short trousers, grey socks, and dark brown shoes. The chair I sit on is too high for me. My feet dangle far above the cold stone slabs of the kitchen floor, and my chin is a little higher than the edge of the table. My left palm rests on the table top, while my right hand holds the handle of a silver spoon. On the table, below my chin, sits a white bowl, made of tin. It is half full of a helping of Kellogg’s Cornflakes, soaked in a puddle of milk. I lower my head, open my mouth, and spoon a dollop of milk soaked yellow corn flakes onto my tongue. I feel them slip down my throat till they are clasped by my belly.

Alone at the table, I look up. My mother stands with her back to our black and dark silver stove, watching me, quietly. Her light brown hair curls over her ears and rests on her shoulders, her blue eyes shine like two of my glass marbles. Her face reveals her kindness, friendliness and calmness, the strength of her spirit, and the tender warmth of her heart. She wears a long dress that falls to her ankles, so it is hard to see her shoes. It is clear that my mother goes to the hairdresser’s to have her hair done, but she does not come back with a helmet hairstyle, as such hairstyles are sometimes described; hers is more like a loose-fitting bonnet.

“Where’s Eric?” I ask, speaking of my brother, whom I now know, but did not know then, was three years older than me.

“Oh, you always ask that,” says my mother. “He’s at school.”

“What’s school?” I ask.

“It’s a big building with a playground. Children go there to learn things,” my mother explains. “You’ll have to go to school one day, when you’re older.”

“Why?” I ask, liking the sound of the playground but not the big building.

“Because like all the children, you will have to learn to read and write, do sums, know about history and geography, how to paint, draw, make things out of clay, Plasticine,” my mother answered.

My mother was a grown-up. If she got the answer to a question one day, she knew she did not need to ask it again. I was a four-year-old boy. To me there was only now, the moment I was in. Yesterday and tomorrow meant nothing to me. My only concern was now. So, if in the moment I attended to I sat alone at the kitchen table, having my Cornflakes for breakfast, I wanted to know why. When I asked where my brother was, my question was as new to me as the light through my bedroom window each morning. I tested my mother’s patience, but she always answered my question.

I pause, suspend my spoon over the milky, yellow Cornflake mush that remains at the bottom of my bowl. Outside the kitchen window, I suddenly notice my father, standing on the grey pavement floor of our small backyard. In his right hand, he holds the black handle of a hammer. He brings the dark silver head of the hammer down onto the top of a nail, to root it into a piece of wood with a loud thud. He looks in a good mood; he smiles, almost laughs, the skin of his face alive with the colors of good health. His hair and eyebrows look more black and bushy than usual, his eyes more blue, bright, intense. He brings the hammer down onto the top of another nail to bed it into the wood with an even louder thud. My father that morning was Noah, building an ark in the back yard. Fortunately, the flood never came. But the flood must be endured, before you can witness the return of the dove with the olive leaf in its beak, and later, the rainbow in the sky over the deep, placid waters.

Each hammer blow falls on the anvil that is the back of my neck, and makes my spine shudder. My spine feels like a stalk attached to the bulb that is my brain. Each blow of the hammer feels like an attempt to stun my brain. I begin to fear that it will burst. The short delays between each thud of the hammer makes the air more tense, as if I waited for a wire stretched to its limit to snap.

“What’s he doing?” I ask, resting my spoon in the bowl for a moment.

“He’s making a hutch,” my mother tells me, with a mild smile.

“What’s a hutch?” I ask.

“You’ll see. It’s a surprise,” my mother answers.

I sway my chin over the white bowl and finish my breakfast in silence, a quiet boy who grew to be a quiet man. I was born an introvert, but I did not know it at the time. My mind goes blank. I lower my head, concentrate on the word ‘hutch’. A new word. I like it, its sound and its strength. Later, I will like the word more. It rhymes with Dutch, crutch, such, much, touch and clutch.

Later, I stood on the kitchen floor, watching my mother spread some coins on the table before dropping them into her purse. Among the pennies and other coins, there was a farthing. The wren on the farthing coin I studied. I loved to look at the wren. I did not know it at the time, but it was the smallest bird to be found in my land, depicted on its tiniest coin. The more I concentrated on the wren, the more alive it became. I felt that if I looked at it long enough, it would sing to me.

The farthing, as I have since learned, ceased to be legal tender on December 31st 1960. I do not miss the half crown, the shilling or the twelve-sided threepenny bit, but I do miss the farthing.