THE WAY IT USED TO BE

It was very calming – the way it used to be. The way the bitter plume of August used to suddenly break through the dust and the smog, and somebody, clad in a t-shirt and flip-flops, would saunter through the yard, a watermelon clutched to their body, and somewhere, close by, a firefly would light up — no, it’s a cigarette; still, a flare from the denseness of the dusk is surely calming.

https://eastwestliteraryforum.com/wp-admin/edit.php?post_type=page

Or else, it used to be that the letters in “Drugstore” – not lit up exactly, but showed some signs of life, and there, behind the thick glass, lives the old apothecary Goldberg – see, you believed it! – no, there is a grey-haired old woman with sausage curls, who surely must have been born, complete with the sausage curls, right here, in the drugstore window, I remember her since I was a little girl… Wait a minute, that can’t be right, I guess it’s her daughter, or a niece, or just a doppelganger, a clone. The mistress of a tiny realm where cough drops and dill water for babies is still a thing – the way it used to be. A tram rumbles by, it’s exactly the same, the same rails and the same cables, and the passengers stare through the blurry windows, their glances lingering on the mean suburban architecture.

The gray stayed gray – the dust, the buildings, the broken stairs.

The meager underpass lighting is oppressive, the way it used to be; just as it used to be, a bulb is either broken or stolen – but, oh miracle, I am no longer afraid of the dark (like I used to be), I don’t tip-toe with bated breath, I don’t hurry, instead, I am walking steadily, with assurance (not like I used to).

When the train passes the station “Dnipro,” you see the same statute and the river, and it’s as if the summer people sitting across from you wake up suddenly, and not a single one fails to stare, eyes narrowing from the sudden light.

Like they used to, the human faces and voices excite me, the heavy, dusty bunches of grapes gladden my heart; like it used to be, there is an expectation of something inevitable and important that is bound to happen — letters, memories, encounters. Like it used to be, the window is ajar, and I don’t want to think that, in just a little bit, everything will change, an early, lingering twilight will descend, bereft of the guileless warmth.

Like it used to be, one lives in the present, postponing the purchase of winter boots until the future. And the future will come, but it will never be like it used to be.

This was in some other life. The floor lamp seemed an exotic alien, the books guarded the secrets of unknown worlds. A cozy evening, patty-pat of unshod feet, the crunch of new snow (remember the yard covered by a down comforter?), shadows on the wall, and the naïve stories in pictures, narrated by my father’s, or my mother’s, or even by my big brother’s voice. The happy times of the slide films. A dusty box full of reels – a veritable treasure! One can’t wait until darkness when one can close the curtains and arrange the chairs – just so.

So much disappears from one’s memory, fractures into fragments (like the pieces of glass in a kaleidoscope), a wall is now just a wall, a floor lamp – just a floor lamp. Nobody peers at the white sheet, it would never even occur to anybody to hang it on the wall, take the cherished box from the attic, and switch off the light.

CHANUKAH

Influenza – the word is ornate, delicate, transparent, like today’s sky. The cold blueness is a definite improvement on the cheerless grayness, with its cotton clumps and felt streaks. The cold December blueness taunts, teases, as if hinting at the fact that there is always room for a celebration, except no celebration in December can last, it must be over by four p.m. Of course, there is still Piazzolla, he’s best after four, towards evening, his heart-rending notes squeeze, wring out, shake out – letters, pictures – like from an old treasure chest. They rip open all the hastily patched-up rents, half-healed scars – and voila, December is spread-eagled at your feet, begging for mercy – the sun has set, and only the spilled tangerines still remind you of the erstwhile anticipation.

Winter wraps around you like a cloak, a cocoon, immerses you in an early twilight. Just sit quietly, — it hums, — don’t fuss, see: a snowball is rolling by? And a sled behind it? And on the sled – somebody ruddy-cheeked, in a shearling coat? Don’t you know who that is?

The sled is pushed off a hill, and – what a dizzying flight! The sled runners creak, the icy surface of the snow tinkles like a silver bell! Your ears stop up from the speed, the daring, the sweet terror. The speed changes your attitude to being. The street is no longer boring. An old lady holding a canister is flying at you, and so does a kid who resembles Gagarin, the cosmonaut, careening utility poles flitter about, houses break into an exotic dance.

Tough and valorous, you are admitted back home; the house absorbs the stomping of your feet, the rapidly spreading puddles, the metal clanking on the concrete stairs. You are no longer equal to yourself — that pale house flower, warily staring into the darkness of the staircase span (through heavy clothes, buckles, a prickly scarf).

The street becomes mesmerizing, it attracts – by the unknown, the endless, the unpredictable. It scares (by its eternal difference from your own home which always stays the same – although how different is my parents’ bright, dorm-like apartment from that other gloomy dwelling, saturated with suffering and whispers, the world of everything that is strange, droll, dispiriting, and sorrowful), and it inspires because only there (outside the walls) exist that speed, that wind, that amazing feeling of not belonging anywhere and to anybody, that separateness, that significance of autonomous action.

A snowball, fashioned by a boy’s cruel hand, hits you in the face. It hurts and it’s humiliating, but there is no time to be ashamed, your mittens are hastily discarded, your fingers burn from the cold, go numb, but – what a triumph – a lopsided ball, heavy as a cannon, flies after the retreating offender, and now there is no time for anything at all, no time to shout “mom,” and in any case, who would you shout it to, the window is tightly closed and, moreover, sealed up with special paper (as if bandaged) and stuffed up (like a sore throat) with yellowing cotton balls, and so your only option is to be hard and courageous, to expel, together with the frozen air, the shyness and the vulnerability of someone habitually led by the hand.

The adults didn’t bother to explain what kind of holiday this was. But I loved this holiday, not remarked on either at school or on TV.

First, my grandma, having summoned me to the corridor, would – chortling mysteriously and carefully glancing around — thrust a ruble or even three into my hand.

Hide it well, — she would whisper, — so the old fool can’t find it.

I am pretty sure the old fool (God forgive me) knew what was going on but kept silent. So, I guess he wasn’t such a fool after all.

Next, we would get ready for an important visit. My tight, Sunday-best shoes (red and brown leather), annoyingly squeaky. The hated dress that I, in a fit of curiosity, tried to cut up with manicure scissors. A long trip by tram.

But already as we approached, the smell of vanilla, cherries, warm dough saturated the air, and rapid steps behind the closed door presaged the longest evening in the warmest home of my life.

Everything else became insignificant, it existed in a different, parallel reality, totally cheerless and alien – the yard, my school, all those lifeless establishments, and institutions – they all were meaningless and totally removed from what was really important.

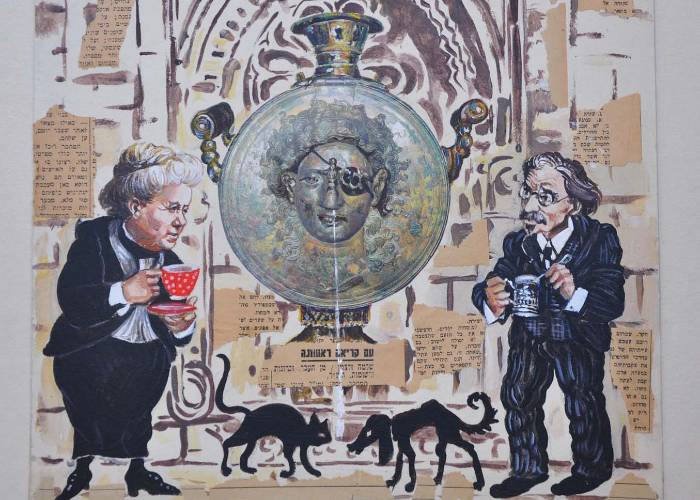

And what was really important was right here, in the old house on Podol, around the round table, with goodness to the right and love to the left of me – grandfather Yosef on the left-hand side and grandmother Riva on the right-hand side. The rest was filled with bookshelves, a grandfather clock, and a little, weights-driven wall clock.

Whiteness is conciliatory. It represents sudden tranquility, detachment, solace. Sounds drown in a snow-white feather pillow. One can imagine oneself to be a Buddhist monk, advanced in years. Smells and memories break through. If you are becalmed (like the nature itself), you can feel the advance of time. The rustle of seconds. The turning of the grindstones. Faces and silhouettes start emerging on the exposed film. The festive flickering of lights.

An elderly man is playing solitaire. Noiselessly, he shuffles the cards, rearranges them, switches them around. Raises the brush to the suddenly apparent perspective. As if he is ordering his life, counting the moments. Determines priorities. Let’s not interfere.

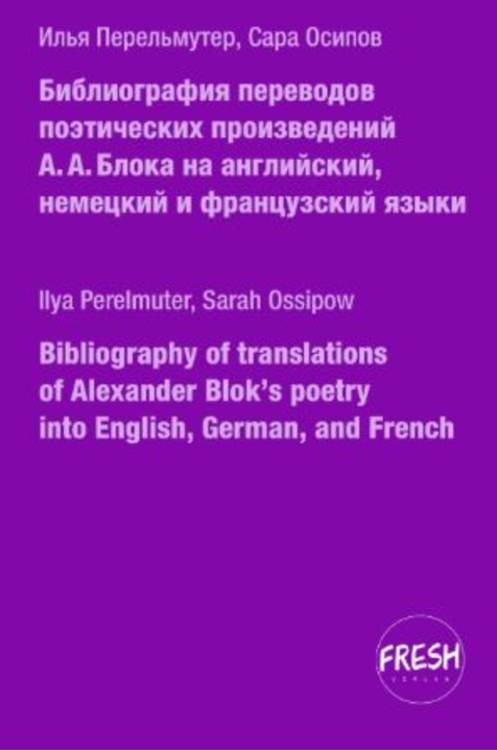

Memories are fragile, like glass figurines. Her eyes are half-closed, some words escape her lips. Funny words, almost unintelligible. Language of exotic birds, bursting with the sounds of an alien life (well beyond the boundaries of your own). This language no longer exists, just like this breed of birds.

She comes from a shtetel, and her grandfather came from a shtetel, and his grandfather before him. What did they have there? A couple of small stores? A heder? A synagogue? A cantor? A mohel? I can’t break through the nailed-down door to that life. Disjointed details, carelessly sketched with a piece of coal — bent shoulders, dusty vestments, and snow – concealing, smoothing out, reconciling.

A cardboard box. The top, bent nails sticking out, separates with a screech. I see him carrying it (arms outstretched) along a narrow path between snow drifts, his face aglow with eagerness and anticipation.

I dip my fingers into the lushness. Incandescent fruit, still attached to the limber branches and verdant leaves. This is what the eve smells like. Citrus.

She closes her eyes, inhales the smell of the snow, carefully gathers the memories together (behind the safety of her eyelids) – the forgotten birds’ language flickers on the right, the blue light of a streetlamp — on the left. Somebody is walking along the path, bowed down under the weight of a miracle. The miracle smells of mandarins, is astringent on your tongue, prickles the roof of your mouth.

Try to remember every detail of their movements. It emerges from the cotton cocoon, fits into the palm of your hand. Weightlessness. Childish fingers learn (through the cuts and the shards) the measure of mindfulness and love.