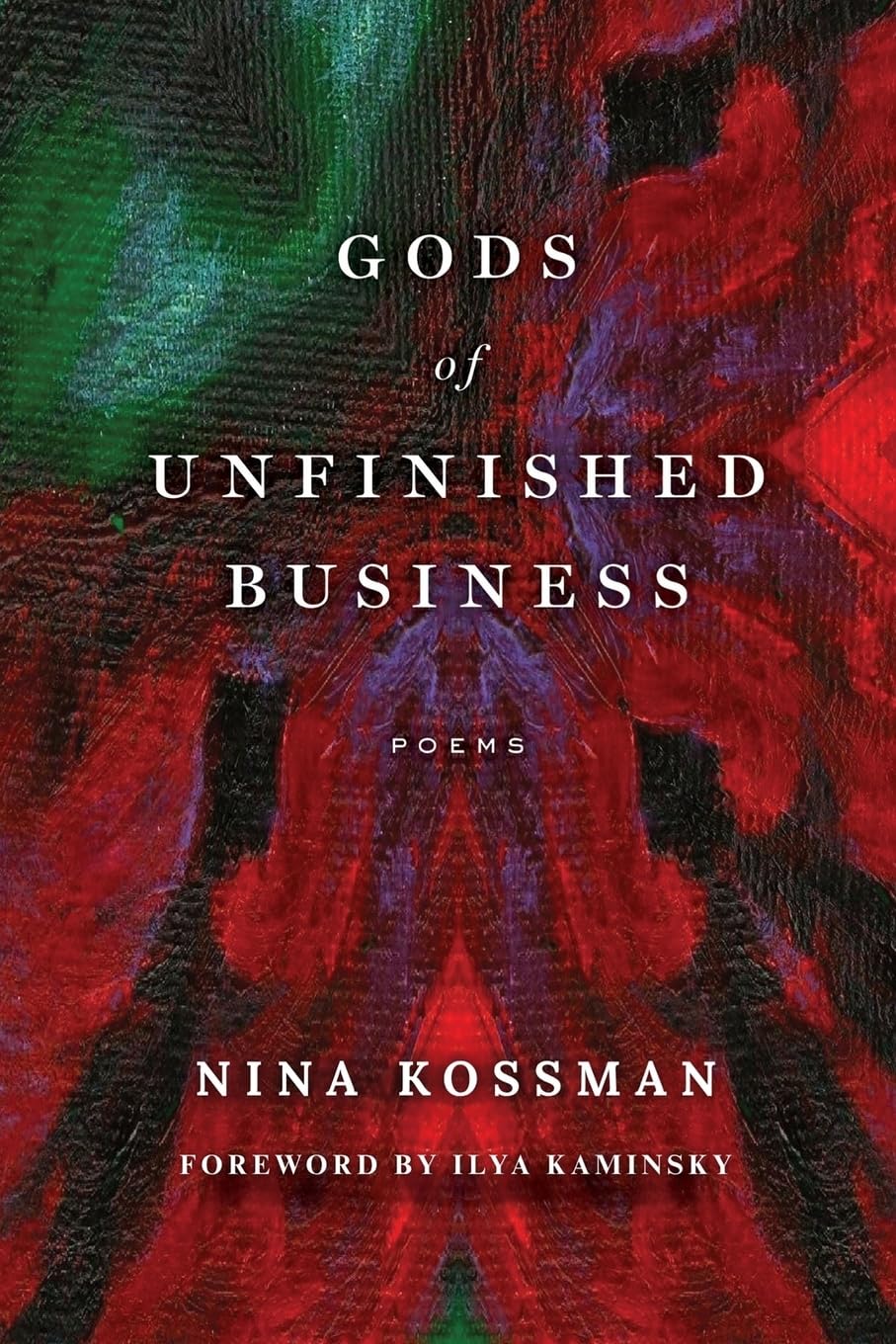

I come to visit a rabbi,

a purportedly wise and learned man.

Are you Jewish? – he asks me

with a self-important look.

Well, undoubtedly, I’m Jewish.

Just take a look at my name;

it will tell you a lot about me.

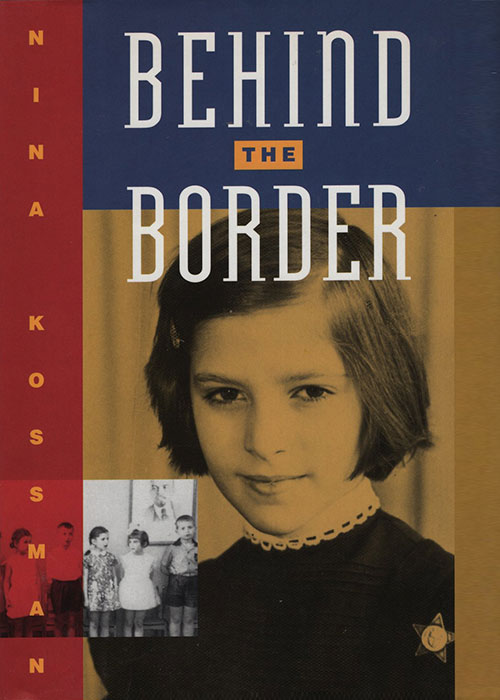

With this name, it wasn’t easy

to live in the Soviet state.

But the rabbi doesn’t care.

He speaks sharply. He interrupts.

Do I light the Shabbat candles

every week before Shabbat?

That’s what worries him,

that’s what matters the most to him.

It’s not nice to lie to the rabbi:

No, I don’t light the Shabbat candles.

But, honestly, I remember

all the signs of being Jewish

that were typical for us.

I affirm: my mom and dad,

my uncles and my aunts

spoke and read and wrote in Yiddish.

But the Rabbi isn’t moved.

Did your mother light the candles? –

he goes on stubbornly.

And again, I must be honest:

“If she lit the Shabbat candles,

that is not what I remember,

but she baked the most delicious

hamentashen for Purim,

and she cooked gefilte fish

for Rosh Hashanah.”

This upsets the poor rabbi,

he is shaking in frustration:

Did your grandma light the candles? –

now he almost screams at me.

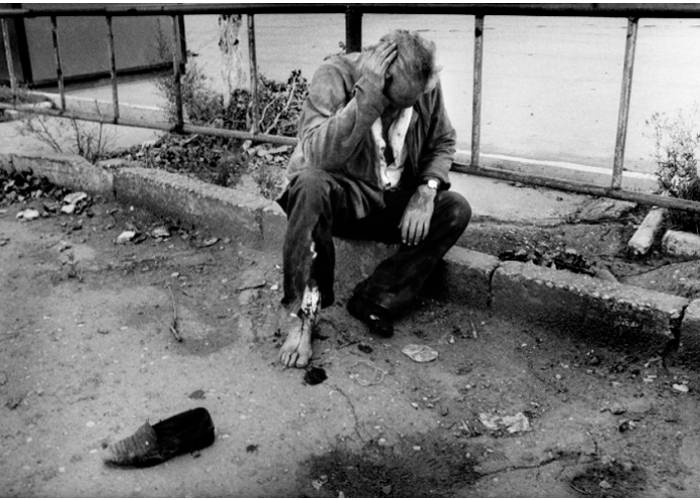

Sadly, I never met my grandma:

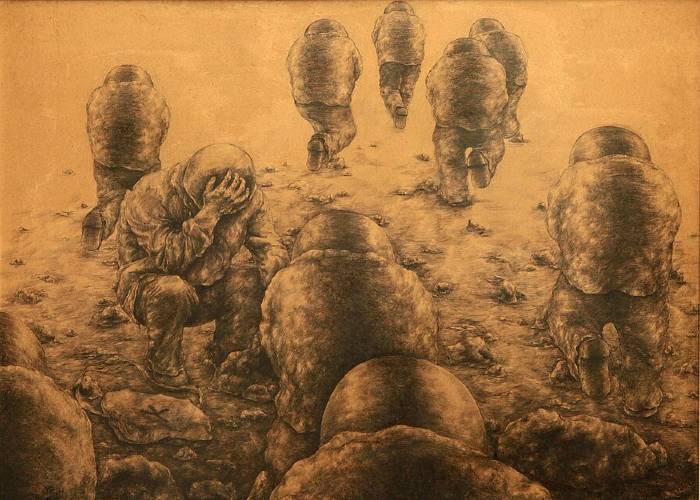

she had been forced into the ghetto.

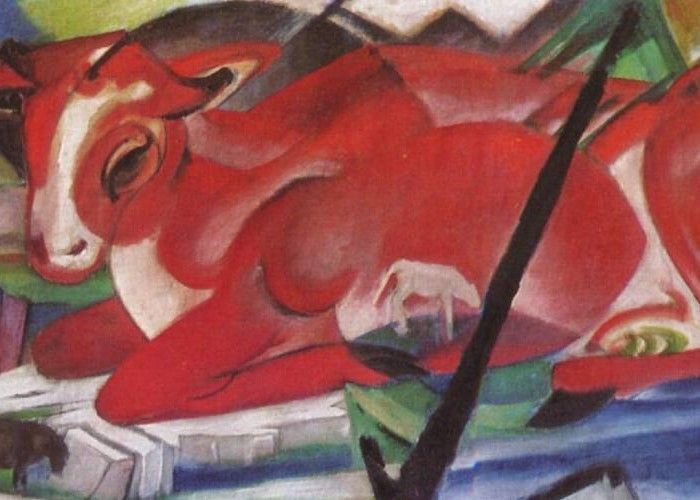

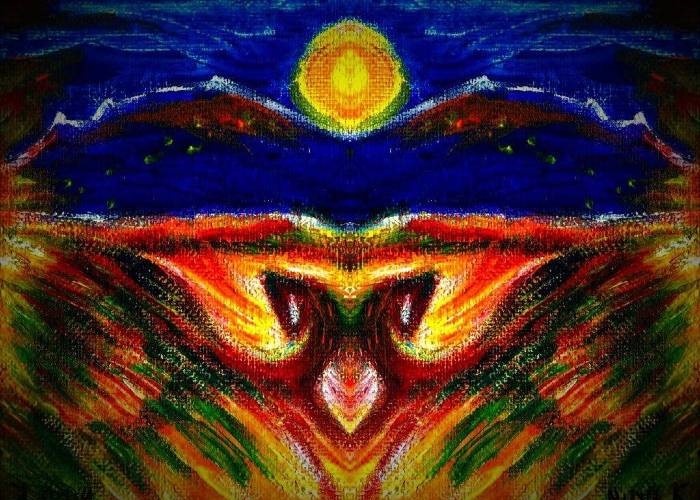

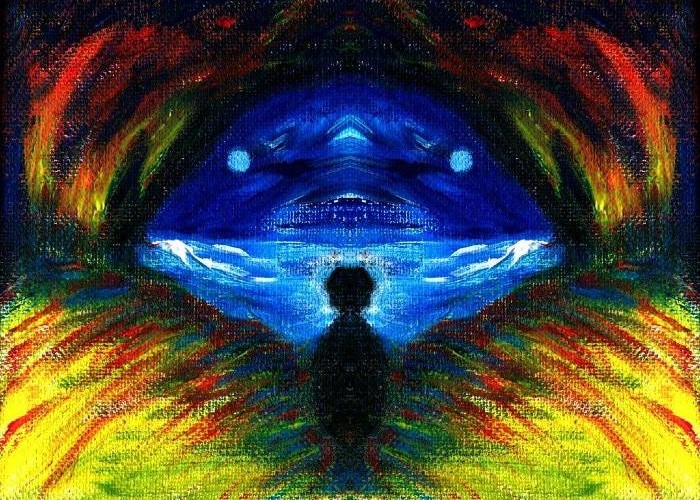

In those days the light was fading,

how could she think of candles?

Not the candles – Auschwitz ovens

burned daily at that time,

so that people of her nation

would burn in fires worse than hell.

Grandmother, surely, was Jewish,

no one doubted that for a moment,

no one asked her any questions,

when they came to take her life.

I’m certainly no wiser than you,

you’re a scholar, an orthodox,

and a highly respected bookworm,

but I can decide without you

who I am and to whom I was born.

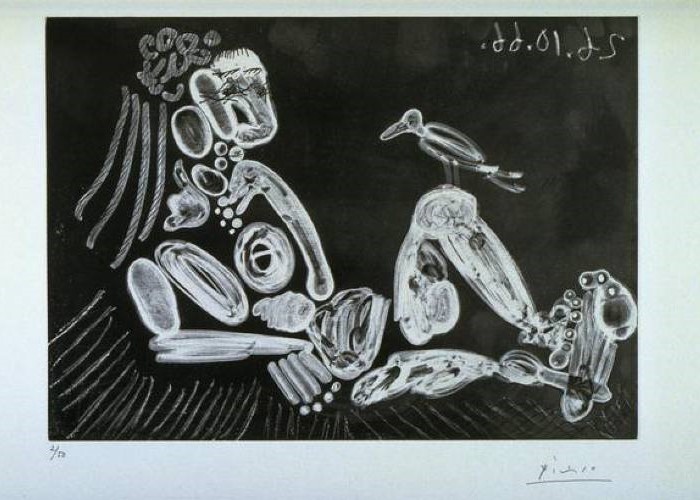

Those ovens are still burning

in my speech; it is full of fires–

take them for your Shabbat candles

and don’t you dare blow them out!