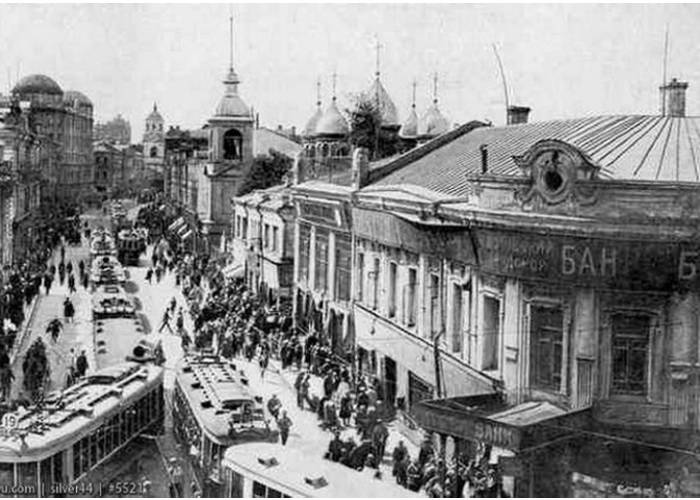

I am writing this from the historic region of Bukovina, on the 7th day of the war that Russia blatantly entered into in Ukraine. The region is located on the slopes of the Carpathian Mountains. “Buk” means “beech”, and the word itself was one that is important in the study of the Cyrillic alphabet. As I hazily recall from my studies of Slavic Languages and Literature, there is some kind of significant linguistic factor as to whether or not the word for “beech” is derived from “buk”, as it is in German, Romanian, and Polish. In Western South Slavic, “Buk” refers to beech or beech mast, i.e. the fruit or nut of the beech tree. However, in Eastern South Slavic, the primary meaning is the root of the word “bukva” i.e. “letter”. As Church Slavonic developed, “buky” was chosen as the second letter of the alphabet of both the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets. In fact, it stands for the “bet” in “alphabet”, or “buka” in the Cyrillic word for alphabet, “azbuka”.

This area has been under Romanian, Moldovan, Austrian, German, Polish, Russian and Soviet rule at various times in history, though not necessarily in this order. They say that is has always remained neutral in different wars, and was one of the few areas that was not occupied in WWII. Which is why I chose to come here for now, as the village where I am at is 12 km from the Romanian border.

With each day of the war, everyone I know was still hoping that maybe it will be the last day and the occupiers will disappear. At midnight on February 23, RF forces were already on their way. On the Thursday morning of the 24th, at around 4.20, all of Kyiv was shaken by a blast, followed by a couple of others, from a cruise missile. They woke many of us up, they could be heard throughout all of the Kyiv oblast’. The blasts were one of the most frightening ones any of us had ever heard. I could not eat anything all day and spent most of it running to the bathroom. My 2 dogs and 4 cats did not seem to notice much, other than that I was extremely nervous. However, the chickadees that I feed all winter were visibly alarmed. They had come back after darting around during the slightly warmer days in the third week of February. My chickadees are very communicative, they like to eat when I am sitting at the table, having coffee or a meal, so that we can observe each other through the window. On the 24th they were extremely agitated and constantly hovering around the birdfeeder with sunflower seeds. A chickadee had flown into the house in 2009, my father caught it and saved it, then he went into a coma and died in 2010. In the summer of 2020, a chickadee surprised us as my mother and I were sitting outside having wine, it flew over and hovered as if in greeting. That fall my mother died. It is snowing in Kyiv and here in Bukovina as I write this, on March 1, I left some sunflower seeds for the chickadees back home in Kyiv, and hopefully those watching my house and 3 cats will feed them as well.

On the morning of Friday, the 25th, more cruise missiles hit Kyiv at around the same time in the morning. Friends of mine who are from the small town of Peremogi, near Baryshevka, which is 100 km from Priluki, a former strategic heavy bomber military base, where there Is also an airport, decided to move across the Dniepr, toward the center, as they were afraid that the bridges over the Dniepr would get bombed and they would get stuck there, unable to leave. They took their dog, loaded up their two cars as much as possible, and drove to my house in Kyiv to see if I was finally ready to leave. As they were leaving, they began seeing videos and posts about RF tanks being in Priluki, Chernigov region, and heading out toward Peremogi and Baryshevka. Eventual destination Kyiv, via Brovari.

When my friend Tamara and her husband arrived in Kyiv, it was around 10 a.m., and events were actively unfolding elsewhere, Kharkiv, Chernigov, Kherson. I was still unsure about whether or not I was ready to leave, my house is 20 km from the center of Kyiv, I have two dogs and four cats, two of which are blind. I had been playing Russian roulette until that day, choosing whether or not to go or to stay, and if I went, what choices would I have to make. About a month ago, I had already traveled to Bukovina to see what arrangements could be made. I was scheduled to return later in February, but my arrangements fell through.

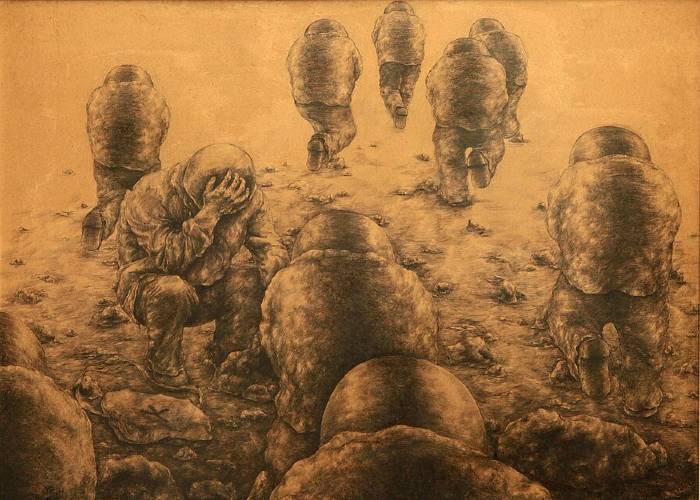

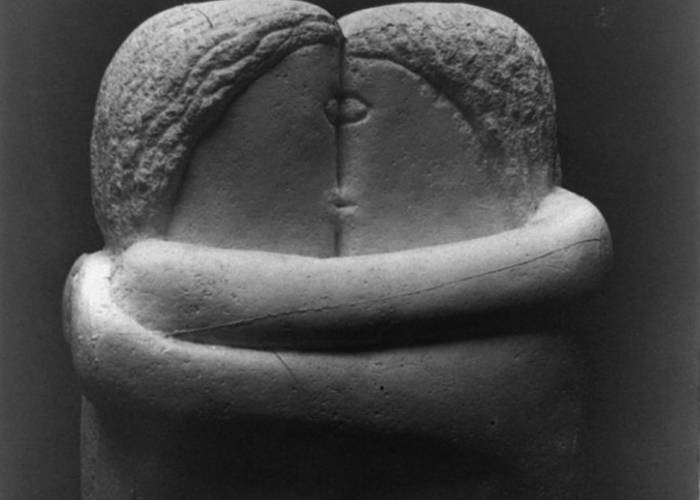

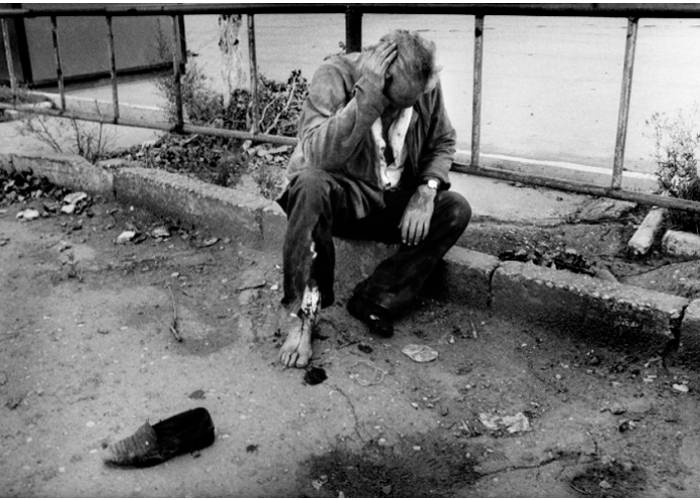

And so here we come to that infamous meme, Sophie’s choice. My family archives, lots of artwork, my library, 4 cats and 2 dogs, what do I take with me? This is the type of decision one can only make under duress. I arranged to leave my house with the alarm system on, with plans to take my two dogs and one indoor cat with me. One other cat would remain outside, she has a doghouse to keep warm in, the two blind cats would stay in their little building where I do laundry. They would be fed by a neighbor. I packed all my important documents, gadgets and charging cables, but forgot a whole lot of stuff, like my toothbrush, winter coat, boots. I left wearing just a raincoat, sweatshirt and leggings, and took a pair of cotton pants and a t-shirt and a couple of pairs of underwear, not even an extra pair of socks. That’s all. My friend Tamara said she had a lot of clothes with her anyway. But at least I took about a month’s worth of medicine, who cares what I would be wearing at this point anyway.

I was still making the decision, should I stay or should I go, for most of the morning. Then I corresponded with my friend, the writer Alexei Nikitin, who recently wrote an incredible novel about WWII, whether he thought it was time to go. It felt like a continuation of his novel, “Bat-Ami”, discussing the best route to take and the best time to leave. This was around 1 p.m. I was thinking we shouldn’t hurry and could leave Saturday morning. But he suggested we leave asap, and he is not one to mince words. We decided the best route would be to take side roads toward Belaya Tserkov, past Vasil’kov, and head toward the town of Skvyra. We left around 5 p.m. on Friday afternoon, expecting to see tanks on the ring road as we headed down the Kyiv-Odessa highway. We bypassed Belaya Tserkov and went past Vasil’kov around 8 p.m., later that night, around midnight, an oil storage facility was blown up there. If we had left the following morning, we would have been stuck.

As it was, we continued on toward Skvyra, where we got stuck at night and could not go any further because of martial law requiring that no one be outside after 11 p.m. We stopped at a store before this went into effect and asked a couple whether or not there were any motels or hostels around. Eventually they invited us to stay in their apartment, they fed us and took us in, though I spent the night with my two dogs and one cat in the car. At least we had blankets with us. We then continued on, the following morning, to go toward Vinnitsa, Khmel’nitskiy, and then Kamenets-Podol’skiy, which has an old Medieval fortress there. As we passed each of these areas, I continued reading the news and finding out what was going on in the rest of Ukraine. Including the areas we were passing through. When we passed Vinnitsa, we heard about how the Ukrainian Air Force had struck down a Russian SU-25 aircraft that morning. So the going was really slow and full of alarming news.

As we were heading past Khmelnitskiy, we were contemplating stopping by to see Tamara’s sister, and were in touch with her along the way. She had promised to bring us some lunch. But by the time we were in the area, she called to let us know that there was an air raid alert and she was going to the bomb shelter. Apparently at 9.30 a.m. RF forces tried to attack a military airport in the region, four RF missiles were launched, but were successfully destroyed by the Ukrainian Air Force.

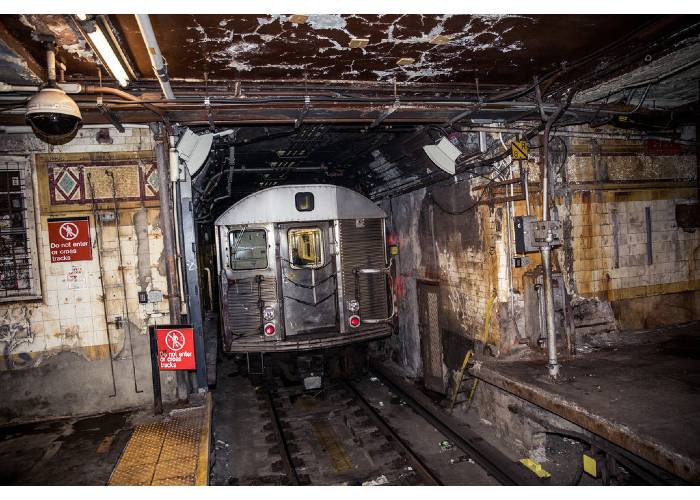

Next place on our way was Kamenets-Podolskiy, I had just been there a few weeks ago, it has a lovely open-air museum with a fortress. As we drove between Khmelnitskiy we could see missiles flying overhead from the direction of the Transdniestr. We took a ring road past Kamenets Podolskiy and headed toward the Chernovtsky oblast’, about 90 miles away. There were four checkpoints ahead of us, and it took us about 9 hrs to get through the first one. We ended up taking naps in the woods by the road until dawn. All in all, it took us about 17 hours to get through all four checkpoints.

When we left Kyiv, there was still Spring in the air, now it is cold and snowing. We are staying in a traditional Ukrainian house, a pyatistenok, with two wood stoves. There is running water and an indoor toilet. The landscape is hilly, the skies are clear. My dogs and cat are staying warm by the stove. When leaving Kyiv, I took all the petfood I had with me, plus whatever there was in the fridge that could go bad, and about 4 liters of milk. We have been able to buy groceries here, but are quickly running out of cash. Neighbors are bringing us beets and other root vegetables. We have chicken necks, onions, potatoes, carrots, and barley, enough to make soup for us as well as for the dogs. Saving their canned and packaged food for when/if we run out of fresh food.

I have been in Ukraine since 1994, I initially came as an interpreter on the disarmament program. Except for two years that I spent in Russia, I have been here ever since. Two years in Uman’, where the military base and depots were bombed this past week, the rest in Kyiv. When I retired, I opened a literary salon and the began publishing books. My parents, who are emigres, came to live with me in 2006. After the Maidan of 2014, I said thank God my father did not live to see this. And now I keep thinking that thank God my mother is not alive to go through this. When I first came here, the words occupation, evacuation, displacement, siege, and blockade were vague and abstract concepts for me. My mother had gone through the siege of Leningrad, then evacuation, occupation, and displacement. She and her parents ran from the Red Army, through Kyiv, through parts of Poland and Ukraine, until they were safe in the American zone in Germany. Her brother was serving in the Red Army and was in Kyiv liberating it from the Germans. My father was the grandson of a Russian writer, Evgeniy Chirikov, and a well-known doctor from Kharkiv, Mitrofan Retivov, who had established a tb hospital there, he had also spent much time in the Donbass area, treating coalminers. Both grandfathers and all their sons served in the White Army. The Retivovs were Don Cossacks that most likely originated in the Stanitsa Luhansaya, now part of the LNR.

When I started publishing books in Kyiv, I was able to publish both great-grandfather’s memoirs. In a sense, I have attempted to recreate and remember their heritage. One of Chirikov’s epic novels was called “Otchiy Dom,” the parental home. As on both sides of my family, everyone had come to America with nothing, having lost their homes, I attempted to recreate a family home, in the spirit of hope and revival that was prevalent in the early days of Perestroika. I see now that we were incredibly naïve, the seeds of evil that had gotten ensconced in the Soviet world after the Bolshevik Revolution were not so readily eradicated. Some would argue that the seeds of evil were already firmly rooted there, before the revolution.

My family and friends outside of Ukraine don’t understand why I don’t just leave. How can I leave, when my whole life is here, my books, my archives, family heirlooms, without which I am a clean slate, aging and on the verge of extinction. Where should I go to recreate myself? I don’t want to go anywhere else, most of my friends are here, trying to survive through this Armageddon. I feel bad enough just leaving Kyiv and not being there with everyone else, along with my three dear cats that I left behind. To date, over 2000 civilians have died in Ukraine. I have no clue what next week will bring and whether or not we will survive.