1

One boy put all his poems together to make a book; he asked his mother for some money, and made arrangements with a friend at a printing press but could not think of a title for his book. So he went to an evil wizard for advice. The boy had no way of finding a good wizard. The evil wizard did not even open his book, just said right away:

“Walk and listen, and the name of the book will find you.”

The boy began to walk and listen. Suddenly he heard: “Citizens, whose child is this?” Not bad, thought the boy. But I’ll walk a bit more. He walked into the subway. “Caution, the doors are closing!” Hey! thought the boy. Not bad for a title. When he got out of the subway, he heard a voice like thunder throughout the district: “Air raid! Air alert!” “This is it!” The boy was delighted. Thank you, evil wizard!

2

All his life one boy was chosing painfully between death and shame, and eventually, this spoiled his obituary.

3

Once upon a time, there lived an invented boy. First, his mother made him up, then his wife made him up, and when his wife stopped making him up for a while, he almost disappeared, but then another girl managed to make him up again. So this boy lived like a fish in an aquarium, and when a new girl walked with him in a park and talked to him, people thought that she was crazy: alone, talking to someone who wasn’t real, yet looking so normal and well-groomed.

4

One boy was offered a publication of his poems in an anonymous anthology.

“But how will people know that my poems are published in this anthology?” the boy asked.

“They won’t,” answered the anonymous editors.

“Then how will they know that I am not in the anthology?”

“They won’t,” they answered him.

“Are you good wizards or evil?” the boy asked anxiously.

“We are anonymous wizards,” the wizards answered.

5

One girl sat on a bench, crying bitterly.

A lady who was passing asked the girl, “What happened?”

“I have a short neck, crooked legs, bulging eyes, green skin, and sparse hair,” the girl answered, still sobbing.

“What nonsense!” the lady was indignant. “Is this really important in our time? The main thing is what’s inside you, what kind of person you are!

“I am not a person,” the girl said, sobbing harder. “I’m an un-bewitched frog.”

6

The parents of one boy were very worried that he was spending a lot of time online, sitting in front of a computer.

“Go for a walk,” they would say to him. “Find yourself some real friends!”

The boy obeyed them, went outside, met real guys, and got imprisoned with them.

7

One girl carried a tomcat in a basket for many years. One day she got tired, so she told the tomcat that now the tomcat was going to carry her.

“I’m a boy, not a girl,” the cat responded and ran away.

8

One girl had an enormous nose, but no one told her about it; she was surrounded by kind and well-mannered people. To help the girl, everyone told her how beautiful she was and how everyone liked her nose. The girl became a famous actress and changed the standards of beauty of her time. Now all the other girls stood in front of mirrors and pulled their noses, trying to overcome pain.

9

One girl was very fond of listening to horror stories at night, but her dad worked long hours and could not always be there for her. So the dad taught the girl to read and gave her Karamzin’s “The History of the Russian State”.

10

One boy said to another boy:

“Everything you do is nonsense.”

“But you, too, all you do is just total nonsense!” said the other boy.

“I do nonsense because I’m a fool, but you are smart, and therefore if you do nonsense, you are a scoundrel.”

11

One boy was asked: Want to die for freedom?

“For whose freedom?” the boy wanted some precision.

“Your own,” the questioners said.

“What is wrong with my freedom?” the boy asked fearfully.

“It will be taken from you tomorrow!” they answered him and sighed collectively.

“I have to die for my freedom today, so that tomorrow they will not be able to take it away from me?” the boy said intently.

“That’s about right,” they answered him. “But you simplify things too much.”

12

One boy wanted to become a literary critic, but he did not like to read books. One day the boy met Rozanov, the number one blogger in Tsarist Russia, and shared his misfortune with him.

“You see the book lying there,” the blogger pointed at a tray. “What’s written there?”

“Will and performance,” the boy read aloud.

“That’s it,” answered Rozanov, “you’ve read the book, now go write about will and performance,” he added, snapping his fingers in front of the boy’s eyes.

13

One girl was ready for anything. She was offered one thing, another thing, and yet another thing.

“No,” the girl answered, “I want it all!”

14

One boy was sent to a train station to meet writers.

He asked: “But how will I recognize them?”

“They are just people in unfashionable leather jackets with beer bottles in their hands.”

Soon enough the boy began to see writers in the streets and the subway, and he wondered how many writers were in his country, and he thought there must be some good ones among them.

15

One boy dreamed of being published in a thick literary journal, but his manuscript was invariably returned to him with a repetitively polite response. One day the boy could not stand it anymore, so he burst into the director’s office and killed the unfortunate man by hitting him on his head with a manuscript. At that moment, some harsh brownies materialized in the office, and breaking the usual rules, told the boy that he would be the department head until the end of time when an offended author would appear and beat him to death with a manuscript. That’s when he understood the deceased director’s deceitful plan.

16

One boy had a goldfish in his aquarium for years. One day this boy overfed his fish, and it died. But the boy hadn’t had the time to ask it for anything, because, ever since his childhood, his mom taught him that they would come and he would be everything.

17

“After the ball, should I call you as usual?” – asked the coachman one of the rats.

“No, go straight to the vegetable warehouse,” answered Cinderella, who, despite her inexperience, had not yet lost her hope of meeting her prince.

18

One boy was very fond of literature and devoted his whole life to it. He was extremely successful, and a small circle of fellow connoisseurs was formed around him. But the boy was not satisfied with the level of his own work, and he painfully tried to find a way out. Once he met a homeless man, an old writer forgotten by the whole world, and he decided to ask him.

“I can’t do anything well,” the boy began his complaint. “Yet I love literature so much!”

“So love literature a little less,” the homeless writer interrupted him. “Literature needs to be hated, too.”

19

One boy did not listen to his mother; instead, he read Borges all the time. Mom said this and that, but he just turned away from her and read his Borges. One day, when something bad happened to him, he turned to Borges.

“I’m not your mom,” Borges answered.

20

One boy lived by using his own mind and eventually he used it all up. So he went to borrow some, but no one wanted to give him any, they just said: go, use your mind. But how could he if he no longer had any left and there was nowhere to get any? So the boy went to evil, clever people to borrow some mind from them at high interest.

“Don’t go,” said a stupid boy to him. “What will you give them for it? Let me just share mine with you. I don’t have much, but we’ll get by, and there, you’ll see, the revolution is just around the corner, and God willing, they’ll cancel mind, ration cards will be distributed equally to everyone, so we’ll be fine.”

21

One boy went the wrong way. He did someone else’s work, lived with someone else’s wife in someone else’s house, wore other people’s pants, and was a stranger to himself. The boy tried to remember when and where he got off his path and remembered how, once, when driving, he saw a “brick”.

22

One boy wanted to give up everything, buy a beach house, and live there, away from people and all the fuss, and starve.

23

One boy had known since childhood that it was wrong to get into other people’s pockets and phones, read other people’s mail and other people’s thoughts, and that’s why, every time they would start to think in his presence, the boy got up and left the room.

24

One boy quit drinking and smoking and said to himself: why haven’t I done this before? Then he stopped eating sweets, drinking coffee, eating meat and fish, and again he said to himself: why haven’t I done this before? Then the boy divorced his wife, and he asked himself: why haven’t I done this before? Then the boy died and he asked himself: why haven’t I done this before?

25

One girl did not write anything herself; she just published books written by other boys and girls. There were more and more books, and the girl could no longer remember everyone by name; boys and girls with books would come and go; even the ones that she would continue to hear from for some time eventually disappeared without a trace, and only the girl stayed, publishing books. Everyone respected and loved the girl, she was all that was left of the literary stream.

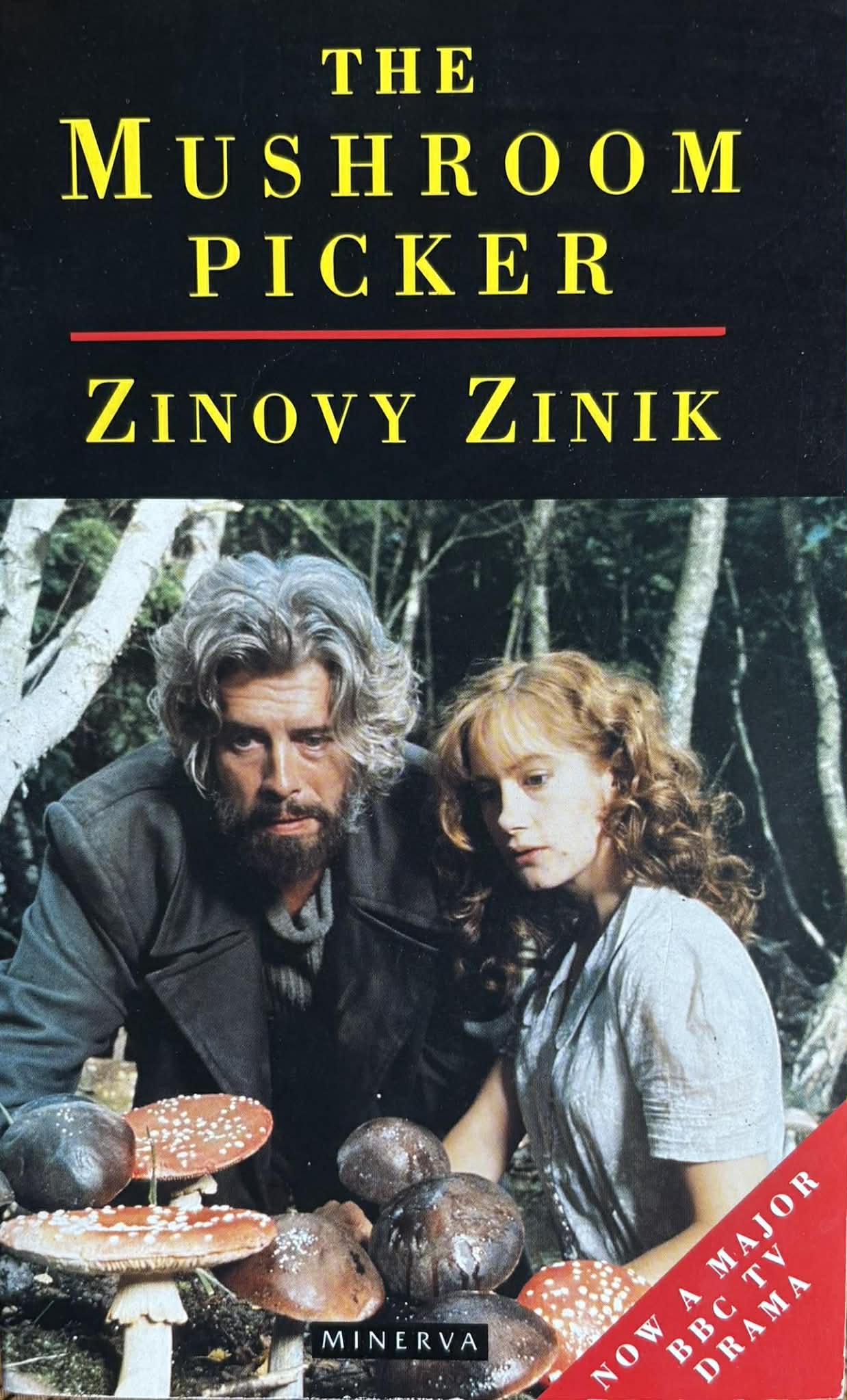

Translated from Russian by Nina Kossman