Слон

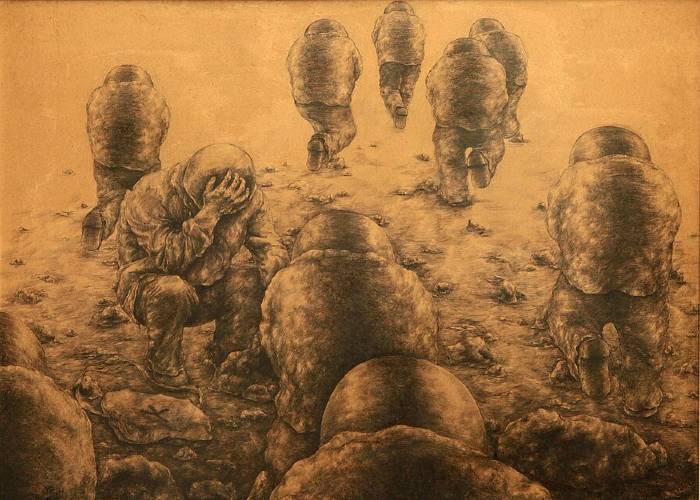

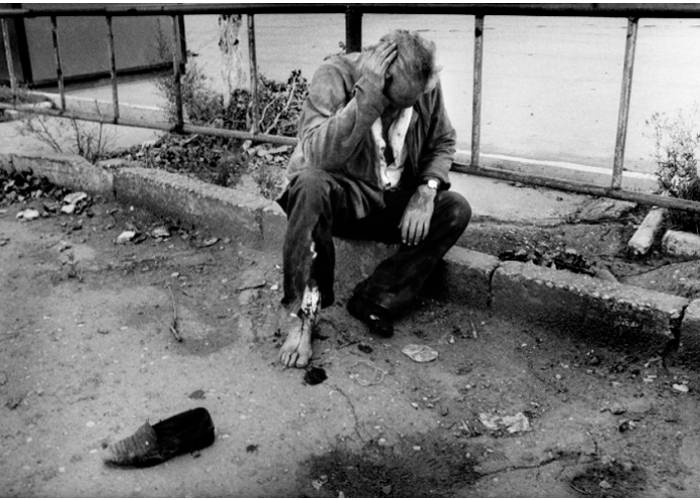

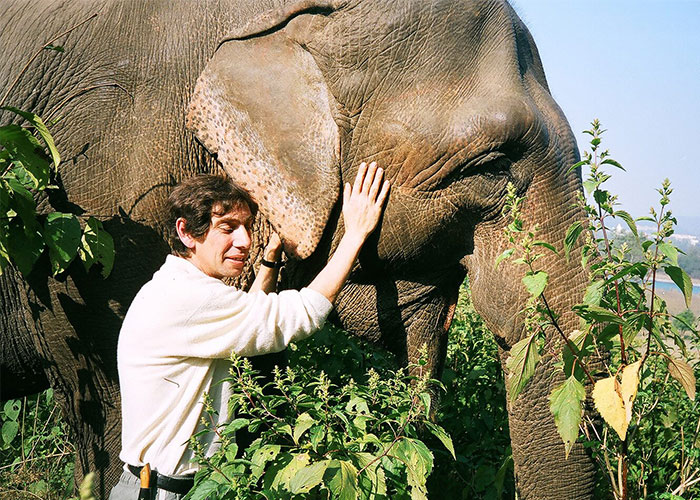

Еще прошли немного и присели у воды. Тишь. Тая прилегла. И вдруг — громкий треск ломаемых ветвей, напротив нас, за речушкой, в зарослях. Страх еще не успел обжиться, лишь прихватил с краю, а перед нами уже стоит мифически огромный одинокий слон с бивнями почти до земли. Стоит и смотрит на нас. Долго, невозможно долго. Спокойно, шепчу Тае, не поворачивая к ней голову, не смотри в глаза ему. Она и не смотрит, лежит лицом в землю, чуть позади меня. А он все стоит, не отводит взгляд. И протягивает хобот в нашу сторону, вбирает воздух. Водит туда-сюда. И медленно погружает хобот в воду, подносит ко рту. Пригубливая, как из ладони. И отпускает воду, как из ладони, стекать вниз. Как это делают индусы, исполняя ритуал речной пуджи. И не сводит глаз. Колеблется, решает. Сканируя тебя этим взглядом всего, послойно — кто ты есть. Тая как-то сдавленно вскрикивает за спиной. Раз за разом. Тише, говорю, не разжимая губ, тише. Черт, вскрикивает она в землю, черт… А он стоит над нами, этот слон слонов, смотрит. Чуть поворачивая голову влево, вправо. Чтоб разглядеть лучше — краем глаза, в котором, кажется, вся вселенная вместе с нами, сидящими далеко внизу. И тут я замечаю, что у самой земли он держит на весу зеленую ветку, перебирая ее хоботом, как четки. Смотрит — и перебирает. Нас, нашу жизнь, как эту ветку, перебирает — «да» или «нет». А глаза текут, борозды с мутными ручьями, то есть не глаза — железы, как же я не увидел сразу — период гона. Он даже не будет предупреждать, топорщить уши, делать ложную атаку, просто вминает ногой в землю и рвет человека хоботом, как ветку. Два дня назад раздухарившиеся индусы отправились в лес на машине и на въезде ткнулись в стадо слонов, задев вожака. Я слышал, сидя у себя на веранде, его странный, вдруг съехавший на фальцет, трубный рев. Что же в нем происходит и почему он сейчас повернулся вполоборота и не смотрит на нас, не хочет испытывать себя этой болью, памятью, не сдержанной яростью? Стоит. Взвешивает. Как эту веточку. Две наши жизни. Aккуратно кладет их на землю и исчезает в зарослях.

Elephant

We walked a little more and sat down by the water. Silence. Taya lay down. And suddenly – a loud crack of broken branches, opposite us, across the river, in the thickets. Fear has not yet had time to settle down, it only grabbed us from the edge, and there he was, in front of us, a mythically huge, lonely elephant with tusks almost to the ground. He just stood there and looked at us — for a long time, for an impossibly long time. I whispered to Taya, calmly, without turning my head to her, do not look into his eyes. She wasn’t looking, she was lying with her face to the ground, a little behind me. And he was still standing, he was not looking away. And he stretched his trunk in our direction, sucking in the air. He moved it back and forth. And then slowly he plunges his trunk in the water, brings it to his mouth. He sips, as though from a cupped hand. And then he lets the water flow down as if from his hand – like the Hindus, when they perform the river puja ritual. He does not take his eyes off us. Hesitating, deciding. Scanning us with this look, layer by layer, completely– this is who you are. Taya screams in a strangled voice behind my back. Once, then again. Hush, I say, without opening my lips, hush. Damn, she screams into the ground, damn… And he stands above us, this elephant of elephants, and just looks. He turns his head slightly to the left, to the right. To see better – out of the corner of his eye, in which, it seems, the whole universe, with us, is sitting far below. And then I notice that, close to the ground, he is holding a green branch in the air, fingering it with his trunk, like a rosary. He goes on looking at us–and fingering it. And thus, we, and our lives, just like this branch, get sorted out—into a “yes” or a “no”. And his eyes are flowing; they are furrows with muddy streams. These cannot be his eyes – these are glands; how could I not see it right away – it’s the rutting period. He will not even warn you, or bristle his ears, or make a false attack, he will simply crush his foot into the ground and tear a person with his trunk, like a branch. Two days ago, some overwrought Hindus went into a forest by car, and right at the entrance they bumped into a herd of elephants and hit the leader. Sitting on my veranda, I heard his strange trumpet roar, which had suddenly slid into a falsetto. What is happening inside him and why is he now half-turned and not looking at us, not wanting to experience himself through this pain, this memory, this unrestrained rage? He stands. Weighting it. Like this twig. Our two lives. And then he carefully puts them both down on the ground and disappears into the thickets.

Translated from Russian by Nina Kossman