That winter, Taya and I moved to Maharashtra and settled at the edge of а tiger reserve in an empty house of our friend the huntsman, Surya. Taya said, “I can’t go to the forest today, my period has begun, but if you really want to see a tiger, let’s go.”

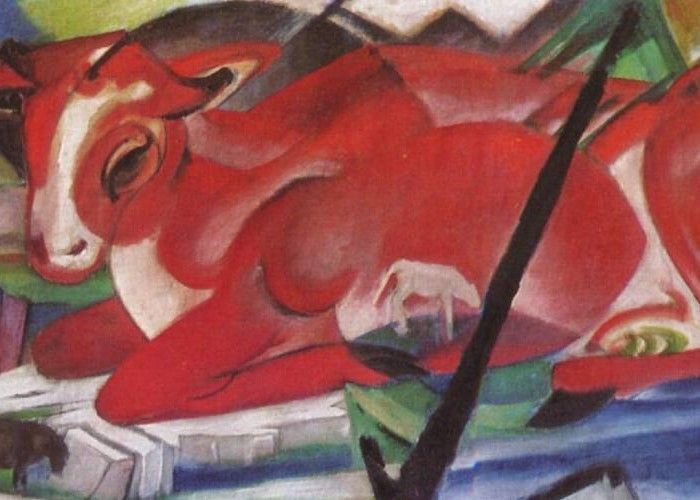

She seemed to be kidding, remembering a taiga rule for women: do not leave the camp during your period–bears will smell the blood from afar. We just smiled and went. I don’t think that what happened later that day was connected with this, but who knows. All these days, we saw no traces of tigers. The forest was magical, the weather, too, and this was our first time in India, so we somehow relaxed that day. We walked on, silent, full of joy, looking around. And we didn’t see anything. There was a herd of deer, suddenly alarmed, sweeping ahead, crossing a clearing. Not running away from us. They cried out in the distance, not calming down. We continued walking, as though not noticing any of it. And then parrots soared up from trees. Again, nothing to do with us. And then agitated langurs start signaling from top branches. It’s all very obvious, and we know it quite well, but it’s as though something inside us has been switched off, we are blissed out, so we just walk on, with these smiles on our faces. And then, in an impassable ravine a few steps away from the path, there’s a loud rustle, as though some big creature has darted there and fell silent. We stopped, squatted, peered, but nothing was visible through the thickets. I even made a joke: they say, don’t squat, so a tiger won’t take you for a wild boar, as it happened to a forester who had been torn apart in this very reserve not so long ago. So, we just walk on, chatting about things. And suddenly– Stop, I whisper to her and squeeze her hand. Tiger! Where? she asks. And then she sees him. Just five steps away from us, lying there, on the side of a trail, up on a hillock, looking right at us. He is motionless, his eyes yellow, his head resting on his paws. One jump, from there to here, and that’s it. I don’t yet know what to do. Climb up a tree? But the closest tree is behind my back and three times farther away than the tiger. And you don’t climb just any first tree you see. I’m going up a tree, she whispers. Wait, I say, stay close to me. I have a knife on my belt, and my hand seems there, but isn’t it funny – the knife’s just a toy against the tiger; my hand moves up to the camera on my chest, I try to focus, but the blades of grass by the tiger’s eyes are in the way. Damn, I whisper, damn … Nothing. He’s lying there, not taking his eyes off me. I sense Taya’s no longer near me. I turn around– she is up in the tree. I return my gaze to the tiger – he is gone, only the grass is still swaying in time with his departure into its depths.

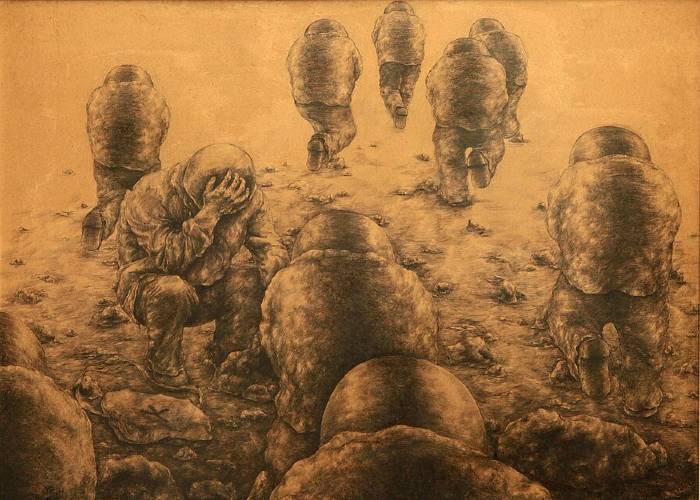

And then, I really don’t know why and how I did it: after all, I knew I shouldn’t do it, and he didn’t go away, he just lay in that thick grass, invisible, waiting just a few steps away from me-– but then, slowly stepping over, I went over to him, still holding my camera just below my face. The grass was taller than me; it was yellow and so thick you couldn’t see your palm on your own outstretched hand. Taya began to scream. Later she would say that she did it in order to distract the tiger, to frighten him off, to save me. Don’t scream, I say, I can’t hear anything here, I stop dead after each step, listening. I turn around to her: look behind your back, cover me, the tiger will go around… She screams, she can’t hear me.

I take a few more steps towards that long gap in the grass. The tiger is standing at the end of the gap, looking at me, and suddenly lets out a roar–not the kind we hear in a zoo. NASA research of tigers’ roar shows that its low frequencies put deer into a state of stupor. The tiger is still there, hiding in the grass. It looks like he’ll bypass me on the right. Slowly, I retreat. I watch tops of stalks: they are motionless. Where is it? One more step back. And then – right from under my feet–he rises up above me. Right above me; I remember that snout and even its exhalation into my face thrown back towards it. And then it backs away. And it’s as if a wave throws me back. And right there behind my back a second one rises, in a mirror image of the first. And he sprints away after the first. A receding crackle in bushes on the hillock, and then, silence.

I stand. Taya is no longer screaming. I’m back on the trail. She climbs down from the tree, and I keep peering into the distance of the path, waiting for them to come out again, to turn around–these are cats, after all… They must have followed us the whole morning for hours. Thank God that these were apparently young, inexperienced tigers, as Surya would suggest later. Well, and also, probably, I disoriented them from their territory, claiming my rights on it with such frenzy. And I’m still alive. Not what you call such an unheard-of experience, but I no longer know what to call it.

Translated from Russian by Nina Kossman.