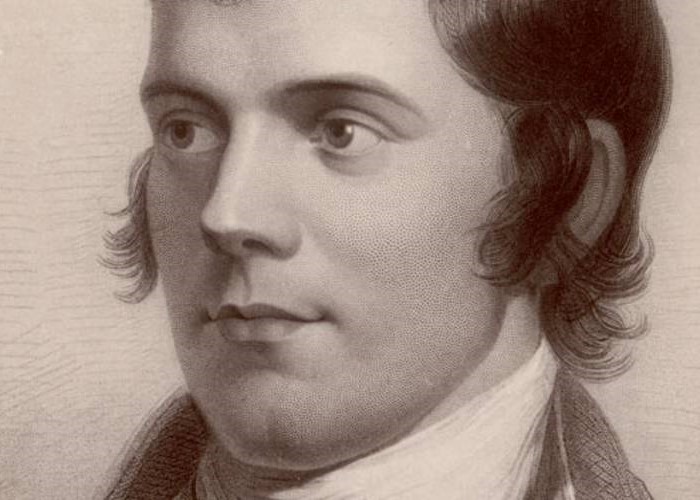

The Original

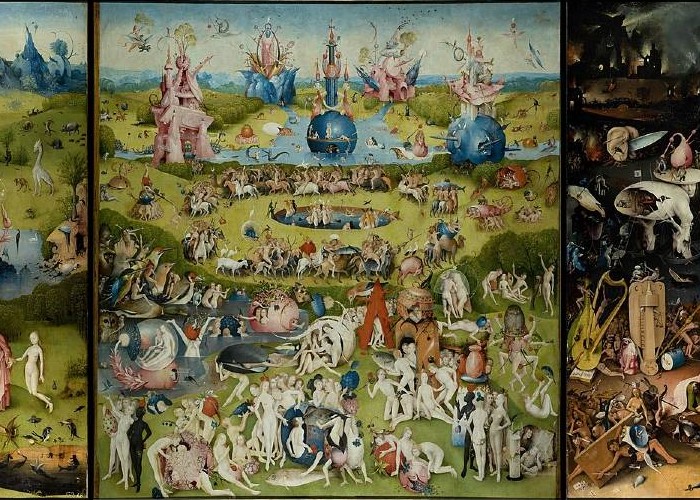

It was freezing on the Campo de Fiori on February 17, 1600.

A crowd gathered to watch a heretic burn alive.

There he was, naked, hung upside down,

punished for denying the dogmas of the Catholic Church,

and while the crowd hooted and hollered,

Giordano Bruno, whose mind was still intact,

despite weeks of torture endured by his body,

(the boot* did not suffice to make him recant),

was composing a letter, in his head, to those

who would stand on this piazza centuries later,

when every child would know the obvious facts

for which he was sentenced to burn today:

that the earth revolves around the sun

and not the other way around;

that God is inside us, and not out there,

a bearded man looking on from a cloud,

taking a cue from old men in cassocks;

that freedom of thought was worth striving for,

and even dying for, even torturously burned at the stake.

He didn’t have time to complete the letter

which he was composing in his head,

as the flames were beginning to engulf his body,

and even his mind, strong as it was, could not work as before.

“The day will come,” he tried to continue in his head,

when everything I wrote would be proven facts…”

This was the last line in Giordano Bruno’s unwritten letter.

In a few hours, his ashes would be collected into a bag,

and the bag would be carried to the Tiber. Opened. Emptied.

* “The boot (“the Spanish boot”) – a medieval torture device.

Italian translation by Paolo Statuti

17 febbraio 1600. Freddo gelido in Campo de’ Fiori.

La folla è accorsa per vedere l’eretico arso vivo.

È nudo e appeso a testa in giù,

reo di aver negato i dogmi della Chiesa Cattolica,

e mentre la turba urla e fischia,

Giordano Bruno, la cui mente è ancora lucida,

malgrado settimane di atroci torture

(neanche con lo stivale* ha ripudiato),

scrive una lettera nella sua testa a chi

si troverà in quella piazza secoli dopo,

quando anche un bambino saprà che è vero

ciò per cui oggi lo condannano al rogo:

che la terra gira intorno al sole

e non viceversa;

che Dio è dentro di noi, non ha la barba

e da una nuvola non prende spunti

da vecchi con la tonaca;

che per la libertà di pensiero è giusto lottare

e perfino morire, bruciato sul rogo.

Ma non fa in tempo a terminare la lettera

che sta scrivendo nella sua testa,

perché le fiamme già avvolgono il corpo

e la mente, non più forte come prima.

“Verrà il giorno” – cerca di continuare –

“In cui tutto ciò che ho scritto sarà provato…”

È l’ultima riga della sua lettera non scritta.

Qualche ora dopo il sacco con la sue ceneri

viene portato al Tevere. Aperto. Svuotato.

___

*Lo „stivale spagnolo”, orribile strumento di tortura. (N.d.T.)

Spanish translation by Alvaro Mata Guillé

En el campo de Fiori hacía frío el 17 de febrero de 1600,

cuando la multitud se reunió para ver la quema del hereje

que negaba los dogmas de la Iglesia Católica.

Mientas la multitud ululaba y gritaba,

desnudo, colgando boca abajo, flagelado,

Giordano Bruno, con su mente intacta,

a pesar de las muchas semanas de tortura que soportó,

(pues la bota que le aplastaba el cuerpo no bastó para que se ablandara),

escribía una carta en su cabeza, dirigida a aquellos

que años después se pararían en la plaza,

cuando cada niño sabría lo obvio,

de por qué fue condenado a la hoguera:

que la tierra gira alrededor del sol,

que Dios está dentro nuestro y no ahí afuera,

sentado con su barba mirando desde una nube,

como los ancianos con sotana;

que la lucha, por la libertad de pensamiento, valía la pena,

incluso muriendo en la hoguera.

No tuvo tiempo de terminar la carta,

la que escribía en su cabeza,

las llamas consumían su cuerpo,

llegaba incluso a la fuerza de su mente que ya no funcionaba como antes.

“Llegará el día”, intentó seguir,

cuando lo que he escrito será probado …”,

siendo la última línea de la carta no escrita por Giordano Bruno.

Unas horas después, sus cenizas serían recogidas en una bolsa,

y la bolsa llevada al Tíber.

Persian Translation by Mansour Noorbakhsh

نامه نانوشته جوردانو برونو

شعری در مورد جوردانو برونو ستاره شناس و دانشمند ایتالیایی قرن شانزدهم که در میدانی در رم به نام کمپو دو فیوری زنده سوزانده شد

شعری از نینا کوسمان

ترجمه منصور نوربخش

در 17 فوریه 1600 در سرمای کشنده در میدان کمپو دو فیوری

انبوه جمعیت برای تماشای زنده سوختن یک بدعتگزار جمع شدند

آنجا بود ، برهنه ، وارونه آویزان ،

مجازات برای انکار جزمیت کلیسای کاتولیک ،

و در هیاهوی جمعیت ،

جوردانو برونو ، با ذهنی هنوز سالم ،

با وجود تحمل هفته ها شکنجه جسمی ،

(غل وزنجیر زندان برای رام کردنش کافی نبود)

در حال نوشتن نامه ای بود ، در ذهن خود ، به آنان

که قرن ها بعد بر این میدان خواهند ایستاد ،

وقتی هر کودکی حقایقی را بدیهی بداند

که امروز او را بخاطرش به سوختن محکوم کرده اند

که زمین به دور خورشید می چرخد

و نه برعکس

که خدا درون ماست ، و نه آنجا،

مرد ریش داری که از فراز ابر ها بنگرد،

پیرمردان ردا پوش ظاهر شود و در

که آزاداندیشی ارزش کوشیدن برای آن را داشت ،

و حتی به خاطرش مردن را ، شکنجه ی در آتش سوختن را

او مهلت نیافت تا نامه ای را به پایان برد

که در اندیشه اش می پرداخت ،

همانسان که شعله های آتش بدنش را فرا می گرفت ،

و ذهنش ، اگرچه توانمند ،اما نه چون گذشته نافذ

“روزی فرا خواهد رسید” ، کوشید در ذهنش ادامه دهد ،

وقتی که هرآنچه نوشتم واقعیت های اثبات شده خواهد بود” … ”

این آخرین خط نامه نانوشته جوردانو برونو بود

چند ساعت بعد خاکسترش در کیسه ای جمع می شود ،

به کنار رودخانه تایبر برده می شود. گشوده . تهی شده.

________________________

The original was first published in Vox Populi, an online magazine of poetry, politics, and nature, edited by Michael Simms.