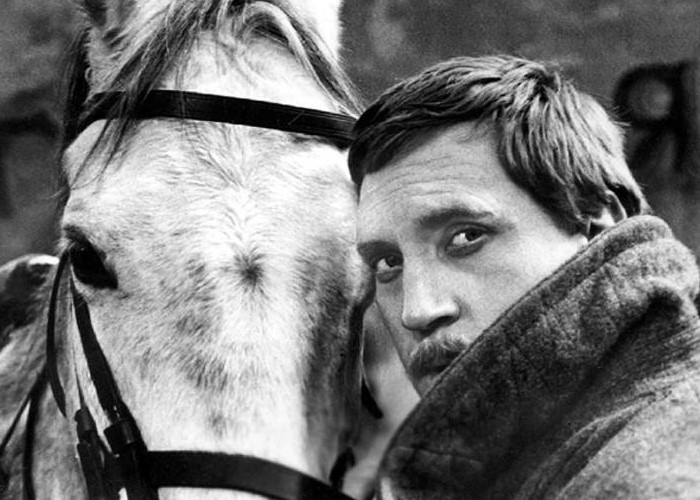

Yesterday, I talked with a man who had no hands,

he had seen me standing at a distance, watching, wondering.

Smiling, he came over and seeing my discomfort laughed,

as he greeted me to put me at any ease –

though a handshake was clearly not an option.

“Fallubah”, he informed me, “Fallubah is my name,

I see the curiosity written on your face, my friend.”

Rightly he had interpreted embarrassment acute.

Why had my curiosity allowed me thus to stare?

“I see that you wondering, waiting to know more”,

with which he raised his arms as if I hadn’t seen.

“The rebels, they did this, clean cut with a machete”.

I winced, but he continued none the less.

“No hands meant no more firing guns, you see,

and more than that, it meant I could not work.

So, I became just one more helpless mouth to feed,

a drain on all my poor family’s resources.

You see, not only bullets are used to win a war.”

“But now,” he told me, “I have found that every day is good,

since the days of fighting have gone away,

and here is the city I have made a better life.

Today I teach my children, so they can read and write,

that way I hope that they will not end up like me.

But more important than those basic subjects,

I tell them of the stupidity of men who go to war,

so, in the future no men will feel the need to look at them,

and feel the kind of pity that you feel today for me.

Yesterday, I learned a lesson from a man who has no hands.

Freetown, Sierra Leone

* * *

Ричард Роуз

Меня зовут Фаллуба

Вчера я разговаривал с человеком без кистей рук.

Заметив, что я издалека наблюдаю за ним,

он подошел ближе и, видя мое замешательство,

в виде приветствия рассмеялся –

рукопожатие в данном случае исключалось.

«Фаллуба, – сообщил он, – Меня зовут Фаллуба,

Я увидел любопытство на твоем лице, мой друг».

Он безошибочно истолковал мое смущение.

Как я мог так открыто показать свои чувства?

«Очевидно, ты хотел бы узнать что произошло».

Он поднял обе руки для лучшего обозрения.

«Повстанцы сделали это с помощью мачете».

Я вздрогнул, а он продолжал как ни в чем не бывало.

«Отрубили кисти, чтобы не мог стрелять.

Более того: чтобы не мог работать,

сделался еще одним ртом, который нужно кормить,

бременем для моей и без того бедной семьи.

Для победы все средства были пущены в ход».

«Но в настоящем, – продолжал он – грех жаловаться:

дни сражений остались далеко позади.

Моя жизнь в этом городе повернулась к лучшему.

Я учу своих детей читать и писать,

И к тому же, что еще более важно,

рассказываю им о безумии и ужасах войны,

чтобы их не постигла та же участь,

и в будущем никто не стал смотреть на них

с той жалостью, с какой ты смотрел на меня сегодня».

Вчера я получил урок от человека без кистей рук.

Фритаун, Республика Сьерра Леоне