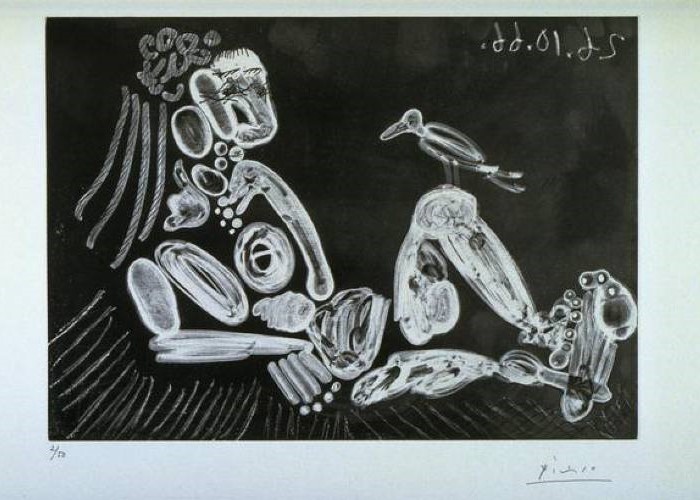

Marxism and problems of linguistics*

this is my mother tongue

not granny’s yiddish

not my kids’ hebrew

that’s how things turned out

no one to blame

no need for excuses

the russian tongue doesn’t belong to anyone

not stalin not putin

not turgenev not the russian nation

the german tongue doesn’t belong to anyone

not hitler not paul celan

the english tongue doesn’t belong to anyone

not ezra pound not nelson mandela

a tongue belongs to whoever’s speaking

leave the russian tongue in peace

at least if you aren’t under bombardment

aren’t burying your loved ones in playground sandboxes

those who are have the right of pain

and also the right to write speak think

in the russian tongue

or in any other.

Translated from Russian by Yana Kane;

English translation edited by Bruce Esrig

* * *

dedicated to all, who **

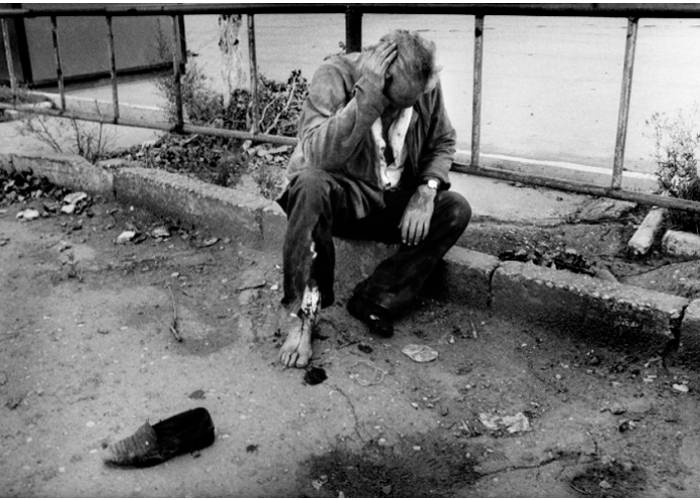

so… I talk with people

from the war zone.

based on what, really?

on my own will,

the caring of others,

the underlying unity,

on the authority of my profession,

on the voice of experience or on hunch,

on skype, whatsapp, viber calls,

on all my knowledge,

and, most importantly, on the strength

of us all being in the image and likeness–

we mustn’t forget about that.

and so… what do they say?

same things, different things—

fear and numbness,

fearlessness and madness,

anxiety, anxiety, panic—

‘no, not panicked, but I just can’t eat,’

‘my medicines are running out,’

‘we’ve stocked up on the food with the neighbors,’

‘I’ve volunteered, now my mom is mad,’

‘my brother got drafted, I am home alone,‘

‘the internet is still working at the moment,’

‘electricity, water and gas are still on,’

‘we’re all in the basement for a fourth day,’

‘we made it out and are in another country,

but my daughter screams, keeps screaming for hours,’

‘my ex has been bringing me food for the past three days,

but what if he does not want to anymore?’

‘but I’m in a wheelchair,’

‘but I don’t know: leave or wait it out,’

‘but what if that highway is caught in crossfire,’

‘but I am not able to step out of the house,’

‘during the shelling we hide in the corridor,

at least it does not have exterior walls,’

‘but I’m worried about my sister—

we are all together here, and she’s alone over there,

they won’t shoot her, they’ll just shut her up,’

‘I can’t stop crying—ninth day in a row,’

‘stay or run—

but mom doesn’t want to, the kids can’t sleep,

and there’s no air, there’s nothing to breathe…’

but what can I say to all this?

I keep silence, ask questions,

try to figure out

what other sources of help to tap,

and that’s what I talk about,

and listen, listen, listen,

and again and again ask: “breathe,”

and I breathe together with them,

and with each one of them in turn,

then I conclude the conversation,

try to recall who am I,

and what my name is,

and then start the whole thing anew.

in fact, that’s all there is:

breathing out, breathing in.

Translated from Russian by Yana Kane-Esrig;

English translation edited by Bruce Esrig

How to Choose the Right Side

This side is the most dangerous for shelling.

This side is most dangerous in a building collapse.

This side is the most dangerous for the seriously wounded.

This basement is the most dangerous for a direct hit.

this staircase is most dangerous for the lower floors.

this maternity hospital is the most dangerous for women in labor.

this neighborhood is most dangerous next to a factory.

this power plant is the most dangerous during an explosion.

This bathtub is the most dangerous for a mother with a baby.

this apartment is the most dangerous

for a grandmother, a mom and a tiny girl.

This sandbox is the most dangerous for burials.

This crossing is the most dangerous for nighttime vehicles.

This border crossing is the most dangerous for volunteers.

This unit is the most dangerous for young people.

These people are the most dangerous to other people.

This language is the most dangerous as a mother tongue.

this language is the most dangerous as the only language

this language is the most dangerous for the press

this language is the most dangerous for the camps

these sirens are the most dangerous for those who stand for bread.

these pipes are the most dangerous when

These weapons are the most dangerous

these people are the most dangerous

This time is the most dangerous

This city is the most dangerous

This country is the most dangerous

This war is the most dangerous

this war

this war

no one is warned. ever.

Translated from Russian by N.K.

___________________________________

NOTES

* “Marxism and problems of linguistics” is an article by Joseph Stalin, published in 1950 in “Pravda,” the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In this article, Stalin criticized the then-dominant class-based approach in Soviet linguistics and set out a nationality-based view of the nature of language. As was the case with all of Stalin’s pronouncements, this was hailed as the work of “The Genius of All Times and Peoples.” His views on linguistics became an unquestioned and all-pervasive dogma for the rest of his reign.

** “dedicated to all, who”: the poem and the translation were first published in View.Point («Точка.Зрения»), a publishing project that focuses on Russian-language anti-war poems (http://litpoint.org).