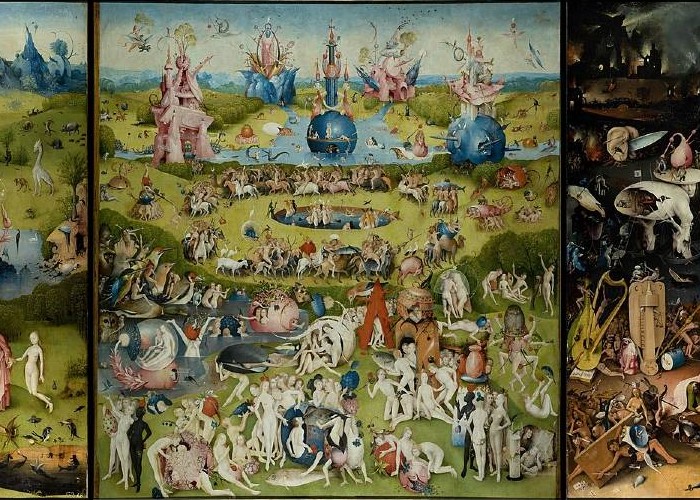

I thought everything that was going on could be found in the book “The History of Moths,” but I was wrong. I thought that moths mistook a candle or a lamp for the light of a bright star — Antares or some other one, by which they had oriented themselves in space for millions of years before us — and would return to the stars when we were gone. Just imagine the magnitude of the error of a nocturnal butterfly, born of evolution even before light sources existed. Even before fires, hearths, and torches existed. What if all of us, and all that we produce, is a mistake made by the moths? What if we are attracted not by the light of truth, but by something else — by the light of some lamp, some lost candle lit to pass the time of sleepless loneliness, or — for the sake of reading some amazing book — for example, that very “History of Moths” which describes the phenomenon of tiny night moths trying to leave the land of birth, trying to conquer interstellar space.

I also remember how once a gas well at the Tengiz gas field exploded in the Caspian steppe, and a kilometer-long column of fire with a deafening roar entered the sky for a year. There was no way to put out the fire, the steppe was melting all around, melting the clay into a siliceous mirror. They thought to extinguish the dangerous flare with a nuclear explosion, but somehow it worked out without it. So, for a year, the birds were off their flight paths and flying toward the deadly flame — just like moths.

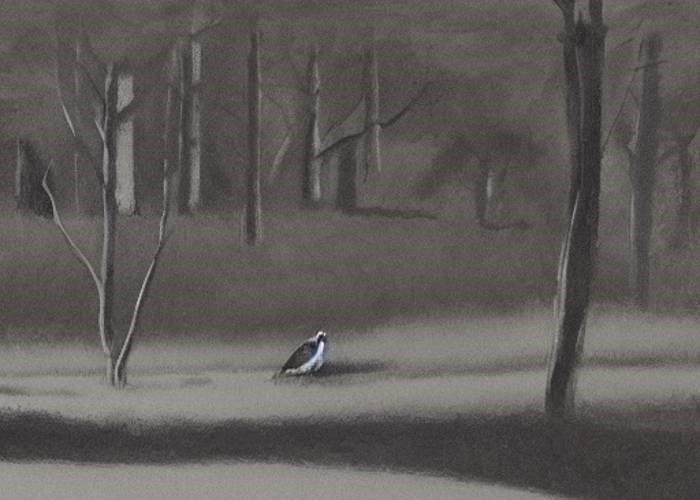

In other words, it’s all about the magnitude and deadliness of the candle that can carry you away from the faint starry flicker of truth. Whence it follows that the faintest and most ghostly glow is more likely to lead you to the right path and maybe keep you alive — even in interstellar space.

Windows of text, hyperbolic nights, and the sun’s smile peering into our moths’ company.

Can another moth hear me in a dream called “The Streets of the Poor” — in which a child’s gaze stops on a pillar of fire? Stops then at the corpse of the woman thrown from the car by the shockwave, at the mute convincing us moths that we must keep flying, that we must not stop, must not look. But the child is watching.

And we go on, to capture the plum shade of the black earth plowed by the explosion. To remember the curve of the woman’s body, the way the diffused light of the sunset slows over it, the way the radio in the car still sounds — the words of a popular song. So we look around — and the last thing we see in the fugitives’ fading consciousness are the cones of waste rock mounds, the spread of light on the hillsides — and the clouds float by and stretch toward the horizon to the west.

Translated from Russian by Nina Kossman