CHAPTER 1. GRANDPA’S DEATH

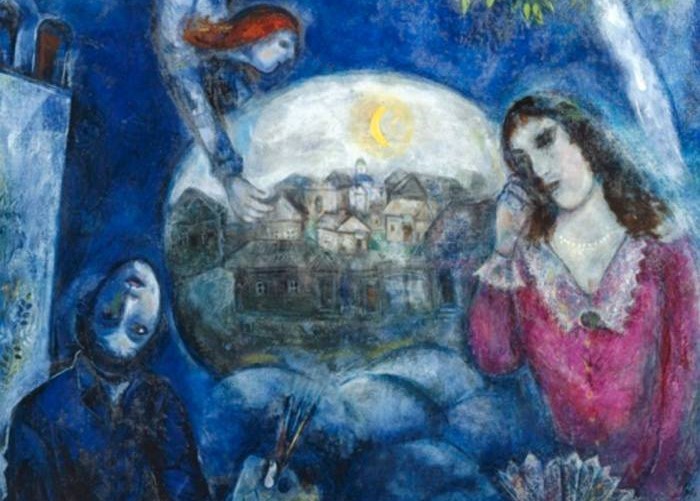

Grandpa’s death split my childhood in two.

The first half was kind, effortless, and light, filled with the sounds of children’s laughter, the mixed scent of sea mud and of the tall pine forest that guarded the sandy edge of the dunes in Jurmala, where our family dacha was located. The memory of the hot sand of those dunes flowing between my childish fingers still warms my soul to this day.

The second half of my childhood was burdened with the grayness of everyday life and the breath of damp stone that greeted you at the entrance to the dark hallway of our city house, the necessity of attending an unloved school, and the awareness that you were Jewish, which meant experiencing constraint and discomfort almost from the first steps of school and street life.

On the day of my grandfather’s death, they woke me up earlier than usual. The cold room floated in semi-darkness; in the window, through the glassy patterns of December frost, the predawn night showed blue. Mom patted me on the head and said that I would go to Uncle Ruva’s for a couple of days, which delighted me. Uncle Ruva, Mom’s younger brother, was kind and jovial. What’s more, I was friends with his daughter, Inna, who was a year younger than me. Uncle Ruva stood next to Mom with an unusually tired and reproachful expression on his face.

At first, I didn’t pay attention to it, but within a few minutes, standing barefoot on the cold floor, I felt that his face oppressed me, awakening a feeling akin to guilt, although I had not yet done anything wrong. As I put on my shoes, I heard the noise of a conversation behind the door, penetrating along with a stream of cold air from the dining room through the gap between the door and the wall.

“Are we having guests?” I asked Mom.

“Yes, your grandfather is unwell, people have come to see him,” she replied, taking my hand. Meanwhile, Ruva opened the dining room door and Mom led me after him.

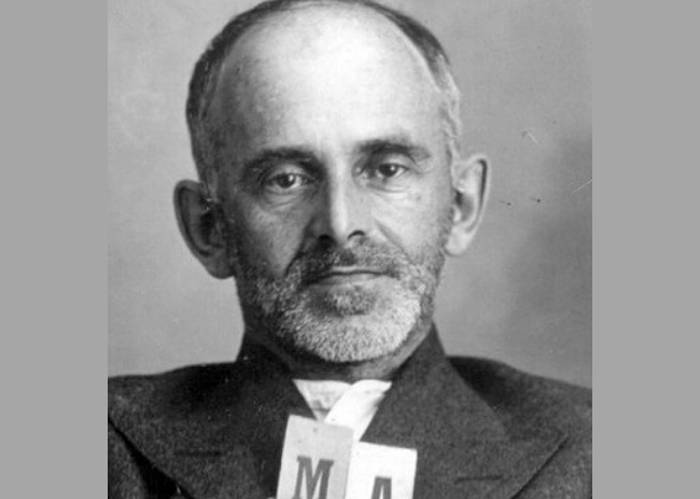

The room was full of people, neighbors and relatives, quietly talking among themselves, glancing occasionally towards the couch. On the couch, my grandfather, Mom’s father, lay on his back, dressed in striped pajamas. His eyes were closed, his face pale and serene, his profile soft and calm. I realize now that it was the first time in my life that I saw a dead person.

At the time, I thought Grandpa was just napping, his face that of a living, peacefully sleeping person.

I also remember a cold, unpleasant wind blowing in from the wide-open window near the couch. The lights of streetlamps trembled in the darkness outside, and it seemed to me that Grandpa’s eyelashes fluttered slightly in time with their flickering.

“Hug Grandpa, say goodbye,” Mom’s voice reached me.

I approached Grandpa and touched his cool cheek with my lips. Then I took a deep breath and felt the light scent of half-rotted leaves typical of late autumn – probably the scent of his skin, reminiscent of damp, crumbly soil. I took another look at Grandpa, whose serene, milky-white porcelain face expressed deep calm, in contrast to the anxious noise of the wind howling outside the window.

“Let’s go get dressed,” said Uncle Ruva, putting his arm around my shoulders.

We exited to the brown wallpapered hallway, donning bulky black Soviet-era coats. I wore a small black coat with a child’s fur hat handed down from my older cousin Alik, and Uncle Ruva wore a long black coat with a black hat that he had received from his older brother Izzy.

Mom and Dad followed us out of the dining room into the hallway. They took turns to hug me and said that they would take me back home in a few days.

“Behave yourself,” said Dad, and something in his voice completely extinguished all my excitement about the trip to my favorite uncle’s. I realized that it was one of those days when fate lurks around the corner, when discontent and fear weigh on your heart, and it dawns on you that the world is not such a kind place at all, and most likely, quite rotten!

Uncle Ruva and I quickly went down the dark stairs from the second floor and opened the door to the street. The door resisted at first but then cracked open, and a biting frost hit my face.

The porch steps were covered with loose snow, snowdrifts approached almost up to our house, and thin icicles hung from the eaves of the houses, shimmering with a yellowish-blue hue in the light of the streetlamps. Uncle’s car was parked nearby, next to the city canal that reflected the flickering shadows of the trees swaying in the wind.

“It’s good that you said goodbye to Grandpa,” Uncle Ruva suddenly said.

“Maybe he’ll get better?”

“I don’t think so, he’s very sick,” Uncle replied in a trembling voice, and I again felt that this was the kind of day that I would never forget, a day whose shadow would lie over my entire future life. Yet this was only the beginning of a day that would later turn out to be so depressing and unpredictable.

We rode in Uncle’s car in complete silence, each lost in his own thoughts. Judging by Uncle Ruva’s grim expression, nothing cheerful was happening in his head. I noticed that adults had two extremes: either the world was perfect, and then they were in a great mood, laughing, praising children, and giving them gifts, or conversely, life was awful, hard, and everyone but them was to blame. In such unpleasant moments, it is advisable not to catch the eye of adults: they may slap you in the face or punish you for no reason. Adults can cover a huge distance, shifting from the perfect world to the terrible one in mere moments. All depends on external factors, with which we, children, also occasionally have something to do.

In general, on the day of Grandpa’s death, the adults’ mood was so foul that even kind Uncle Ruva was sour and unhappy. Now I understand that he obviously loved his father, my grandfather, very much. Meanwhile, I was thinking about how Uncle’s car was newer than ours, their apartment nicer, and their daughter Inna received more praise from her parents than I did.

My main source of praise had been Grandpa, who taught me to read and count when I was just three years old. Since then, he took every opportunity to extol my abilities, telling all neighbors and relatives that a young genius would soon conquer the world. Grandpa’s praise, along with the nods of acquaintances who did not dare contradict him, colored my childhood in rosy hues and sparked ambitious impulses toward perfection. I sincerely, with all my soul, strove for goodness, obeyed my parents, and diligently practiced arithmetic and reading Andersen’s fairy tales. Now, anticipating Grandpa’s departure to another world, I felt uncertainty and fear about the challenges awaiting me, fear that I would not be able to conduct myself with dignity in the cruel world of childhood.

Speaking of the cruel world of childhood, I mean, of course, the unloved school and the street – but more on that later…

Arriving at Uncle’s, I received the gracious permission of his wife, Aunt Ella, to climb into bed with my sleeping cousin Inna. Such a thing was rarely allowed for us, but it was an unusual day. Uncle Ruva said I could skip school due to special family circumstances, hugged me, and muttered that he was going back to Grandpa’s. I quickly undressed, slid under my sister’s warm blanket, and before falling into a deep sleep, I still managed to feel the silky, smooth fabric of her pajamas.

We woke up late, around ten o’clock. Aunt prepared toast, eggs, and tea for breakfast, and we began eating, talking about the various nonsense that fills the heads of children at the age of 9-10.

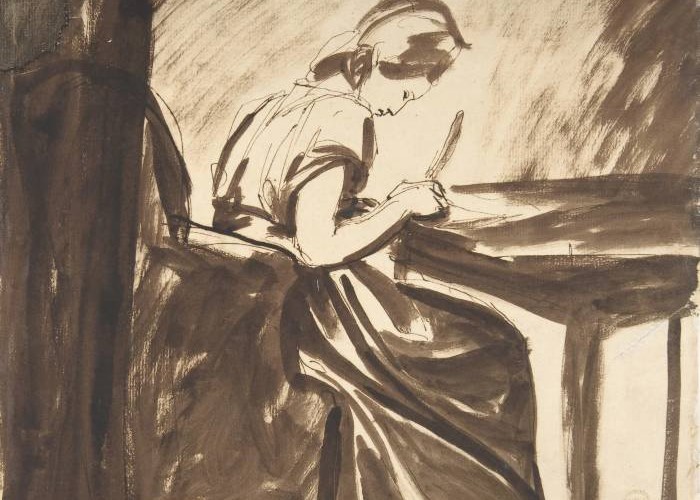

Then the conversation turned to Grandpa, and we almost quarreled because my cousin said it wasn’t a big deal if Grandpa died soon since we still had many living family members. I got angry and shouted that she said that because she had another grandfather and grandmother, her mother’s parents, while he was my only grandfather – and this was the absolute truth, as my father’s parents and his little sister died in the ghetto during the war, and my mother’s mother died very young even before the war. Then we made up, but my mood was ruined. I settled in my cousin’s room and began reading Jules Verne’s In Search of the Castaways, a book I had started once before but abandoned. This time, with bated breath, I followed as Glenarvan and his companions tried to decipher the document drawn up by Captain Grant. This fictional world was so alive and interesting that I forgot about the troubles of my real life. Absorbed in the book, I didn’t notice how half a day flew by until Uncle Ruva returned. His face was miserable and immediately brought me back to real life. At my questioning glance, he blurted out in one breath:

“Grandpa is dead, we have buried him.”

Tears welled up in my eyes, but I didn’t want to be seen crying. I grabbed my coat hanging in the hallway, hurriedly put on my shoes, and ran out of the house, shouting at the door that I was going to gymnastics practice. I did officially have practice that day, but I clung to that excuse just to get away from everyone and be alone.

Outside, I saw that the snowdrifts and the heavy snow-covered fir branches were flooded with the afternoon sun, the snowflakes sparkling like the purest water diamonds. The towers of Riga’s old cathedrals, the half-frozen city canal, the white trees and bushes – everything looked at me, breathed freshness and shone, but did not please, it was all alien and unpleasant. I wanted to run away from living nature, which no longer had a place for my grandfather, and I began to run, run, without respite, until I stopped because I could no longer breathe. My heart pounded loudly and rapidly, like powerful pneumatic drills ripping up the asphalt to lay pipes or cables. I discovered that I was near the gym where I did gymnastics – fate must have led me there on its own.

A boy ran out of the building and, stopping sharply, called me by name. It was Sergey Bondarenko, or Bondar, as everyone called him. Bondar was my friend at school and in gymnastics. I thought he was attached to me because of my success in school and the gym – I was the best at both, probably thanks to Grandpa’s efforts and my Dad’s strong genetics. I loved Bondar for his bravery, insensitivity to dangers and insults, and his familiarity with the practical details of life, about which I knew little. He knew how to use money and goods correctly, was acquainted with shopkeepers, policemen, and street drunks. I loved Bondar for his brazen ability to live and be the boy whom beatings at school and home did not hurt, although they did beat him – especially at home – often, for no reason, and mercilessly. Bondar’s parents were people with hard fates. His father, a war veteran-invalid without one leg, and his mother, a cook in a small, dirty Georgian restaurant, often got drunk and beat Bondar, taking out on him their anger at the ungrateful Soviet state that denied them a decent, humane existence.

Bondar was one of those boys who knew all the ins and outs of street life and were friends with the right people to whom could always be turned to for help and advice. After another beating, Bondar often threatened to run away from home and join some street gang, but his threats had no effect on his unhappy and angry parents. At the same time, they liked my friendship with Bondar, probably because I was from a well-off family and was the best student. I believed that Bondar, despite his terrible family, occupied a more solid position in the world. He was more mature than me, laughed at expressions and jokes I didn’t know or understand, and entered the adult world without any difficulty. And most importantly, Bondar was Ukrainian, not Jewish, so he didn’t have to feel awkward and embarrassed because of his nationality.

But on that fateful day of Grandpa’s death, by the time I met Bondar, I was already nervous and angry, and I wanted to indulge my grief in complete solitude. So Bondar could not have appeared in front of me at a more inopportune moment.

“Where have you been?” asked Bondar.

“Nowhere, my grandpa died today.”

“My grandpa died a long time ago. And the coach was asking about you. Such an annoying coach, always sticking his nose everywhere. I think he’s Jewish, he’s got a Jewish face, and his name’s strange – Havkin.”

There was a pause. We had never talked about Jews before, and Bondar probably was sure that I was Russian and would happily support what was a common theme among the kids regarding greedy and smelly Jews. I felt a chill reach my core, and my lips trembled, but I tried to breathe as if nothing was wrong. Bondar shouldn’t have seen that I was short of breath. I hated him and hated myself for not telling him right away that I was also a Jew.

Turning my back to him, I quickly walked away from the gym. Bondar caught up with me and walked next to me.

“Leave me alone, I want to go alone,” I hissed through my teeth, but Bondar continued to walk next to me, not lagging a step behind.

Suddenly I stopped, turned around, and threw in his face:

“What a bastard you are.”

Then I threw my right fist towards Bondar’s face and felt his nose give way under my blow. Blood gushed from his snub nose, he was momentarily stunned, but then returned a hefty slap. We grappled and began to hit each other in the face and stomach, flaring up and fighting fiercely, like bitter enemies. I was stronger and kept throwing him to the ground over and over, but he did not give up, jumping up and continuing the fight again and again. Drenched in sweat and blood, we continued to beat, tear, wrestle, and choke each other, insulting and degrading each other with words that became more and more heated, stupid and mean, but the words Jew or Yid were not thrown into the air. I do not think Bondar ever understood why I started that fight.

Today I cannot recall the exact end of our battle. It seems that some adult, strong man separated us.

Coming to my senses in the dark, I recognized the street and buildings in the vicinity of Uncle Ruva’s house.

The battle charge slowly faded, and reality began to make its way into my brain piece by piece, at first only through the eyes. There was the bridge over the city canal and the park with snow-covered fir trees.

The brackish taste of blood in my mouth, torn clothes, bunched-up socks, pain in my fingers and a burning left ear – it all came to me gradually, became reality and fell on my shoulders as a heavy burden. I suddenly felt my knees and arms shaking, realizing how tired I was. Finally, Uncle Ruva’s house appeared, and I understood that there was refuge, light, peace, and love. With a sigh of relief, I pushed the high entrance door, and memories of the past day – Grandpa’s death and the fight with Bondar – came washed over me, along with the smell of stone, characteristic of all Riga entrances. I saw no way out of what had happened, just breathed in the cold air of loneliness and despair without plans for the future. Clinging to the railing, I slowly climbed to the third floor and rang the doorbell of the apartment. It was about nine o’clock in the evening. I had never returned home so late without permission.

Uncle Ruva opened the door and froze in fright, seeing my bloodied face and dirty, torn clothes.

“Thank God, you showed up!” he exclaimed.

“Did you get into a fight?” Uncle continued, but I, without answering, walked into the dining room, feeling the gazes of my aunt and my cousin on me. Then, without asking anything, Aunt helped me wash up, put on some adhesive bandages, and fed me. Surrounded by sympathy and family warmth, I sat silently and thought how much I loved Uncle Ruva and his family for this silence.

Then they sent me to bed, but I couldn’t sleep for a long time, tossing and turning from side to side. After a while, the door cracked open, and Uncle asked, without entering the room:

“Can’t sleep? Mom just called; she says Sergey Bondarenko’s parents are worried because he hasn’t returned home from practice. Did you see him today by any chance?”

“No,” I replied, burning with shame in the darkness.

Bondar did not return home that evening or in the following days. They searched for him in all possible places where they search for missing children, but to no avail: Bondar had disappeared, vanished, evaporated like smoke.

The day after he disappeared, a mustachioed policeman showed up at Uncle Ruva’s apartment and asked me about Bondar, as well as about my bruises and scratches, but I easily got rid of him, saying that I had gotten into a fight with an unfamiliar boy in the park. He quickly left me alone, and I even thought at the moment that if all investigators questioned suspects in such a manner, it was no wonder that so many suspicious characters were roaming the streets of Riga at night.

So that’s how I lost my only grandfather and my only friend, all in one day. I continued to attend the school I hated for another two years, until they transferred me to another, where my life was to change completely. But more on that later…

As for Bondar, I am somehow sure that he is alive and did not drown in the city canal, the Daugava River, or the Baltic Sea. Those are all the main nearby bodies of water where drunks and children usually drown. Most likely, he is very far away now and enjoying his life there without being beaten by his parents. Although he was lost to me, it is possible that I may still find him one day and pull him to me by the thin thread that connected us once. When I close my eyes before sleep, I sometimes imagine how I bring him back, hold him in my arms without letting go – and we become friends again. I am also positive that before disappearing, he completely forgave me, more completely than I forgave him.

Translated from Russian by Philip Nikolayev