When she had Sociology, the most pointless subject after maybe PE, Dasha always took a seat in the last row, where, feeling safe and invisible, she could slumber, read her favorite book, or, as she was doing now, think about the uncharted depths of her latest homework assignment.

Next to her, red-haired Marsha, nicknamed Marmoset, was drawing another railway car on the desk, making the elaborate train longer.

“People need a family to satisfy their natural desires and to form a social unit,” the professor dictated.

“Pardon me, what kind of desires?” Marmoset asked him with exaggerated politeness.

“Natural ones,” answered the professor, looking vain and perfect like Mary Poppins. He pushed up his glasses and droned on.

“Cool. He didn’t blush at all,” Marmoset said. Then she focused her eyes on Dasha and put her pencil aside.

“What?” asked Dasha.

“Just look at you! You look really skinny.”

“So what?”

“When I was sixteen, I was the most anorexic girl in class,” said Marmoset. “I starved myself for days and threw up when I was home alone. Everyone wants to have a nice ass.”

*

The doctor was a family friend. In old times, he had worked with Dasha’s father. As a friend, he often came over to have mint tea, tell a couple of old jokes, and offer a piece of free advice.

“Yes,” said the doctor to Dasha’s Mom. “The girl looks too thin and pale. What was her normal weight? 125? I see.”

He usually spoke as if Dasha were deaf or far away. Listening to his words, Dasha fixed her eyes on a lonely slipper on the floor. She felt sad and small.

She was weighed on the bathroom scales, which Mom had fished out of the ancient dust under the sofa. It turned out, Dasha had lost sixteen pounds.

“Has anything like this ever happened to her before?” the doctor asked.

Mom rolled her eyes. “Twice,” she said. “I call it emotional stress. It happens every time she falls in love.”

And Mother started telling the doctor about Dasha’s emotional stresses. About her falling in love for the first time at fifteen, the second time at sixteen, and now at nineteen. These stories were told in agonizing detail as if Dasha were deaf or far away. Each of them sounded rather like a suicide attempt than a romantic story. Listening to her mother, Dasha felt ashamed, as if she was hearing and thinking things she shouldn’t be hearing or thinking.

“Mom, stop it,” she protested.

“Good people have nothing to hide,” said Mom, without even turning her head to look at Dasha.

Yes, Mom firmly believed that good people had nothing to hide, and that was why Dasha was never allowed to lock her bedroom door. Mom read her emails, checked the contents of her handbag, and stopped talking to her altogether when she surmised Dasha was not quite frank about her personal life. If Dasha was frank though, Mom brought all the hurtful details up later, every chance she got. That was why, for years, Dasha had been building a tank around herself. The tank was invisible and did not have a large-caliber cannon or machine-guns, but was comfortable enough to live in and look at Mom through a periscope.

“Find something to take her mind off these things,” the doctor said. “She should be all right. How soon? No one knows for sure.”

The next day was Saturday. Dasha spent the whole morning in bed, where the pillow had the same comforting smell she had remembered from the days before her emotional stresses. For dinner, at Mom’s firm insistence, she had an enormous helping of rice and washed it down with a large mug of compote, but an hour later another few pounds of her weight disappeared as though by magic.

“Good heavens, you are as thin as a rake!” said Mom.

Dasha imagined herself as the horticultural implement with strong steel teeth, and the picture made her cringe. No, she thought, I’m not a rake. I’m thin and soft and tender, like a shadow.

Just two weeks ago, Dasha Prosol had looked pretty and solid like a young champignon. Now there was nothing left of that: now she looked frail like a flower growing in the shade. Only her hair remained the same: smooth, with lovely small curls over her ears.

Left alone at last, she examined her new self in the mirror. She liked her body despite the fact that it lacked the curvaceous geometry she had seen in adult videos. Her breasts were high; her neck flowed with gentle elegance into the supple shoulders; the bones didn’t stick out. She had not just lost weight; in some mysterious way, she became a shadow of herself.

When the sky got dark, she decided to go out for the evening.

“You’ll be back home at eleven,” Mom said, “if you really love me and value my advice.”

“Mom, do you know how old I am?”

“Then you’re not going at all.”

Dasha opened her mouth like a surfacing fish.

“Don’t make me yell at you again,” said Mom. “You know how I hate yelling but you always try to drive me crazy.”

*

The current emotional stress of Dasha Prosol was Stanislas, a big-framed, clumsy guy with shaved head.

They were walking along a poorly-lit alley of black pyramidal poplars. The sky was high and full of stars shining fiercely as if it were the last night of the world. The air smelled of young leaves and sticky buds. At the far end of the alley, there was a dark arch and a bus stop swarming with sleepy, shining buses. Stanislas kept a tedious silence; Dasha was tensely silent. She felt uneasy.

“Are you going to say a word or two before midnight?” said Stanislas. “I don’t even ask for a dozen. I feel kinda stupid when you don’t say anything at all.”

“What? Oh, sorry. I’ve been writing an essay about Thomas Hood. His life, ideas and so on. The deadline is Tuesday, so I’ve got to hurry. I’m thinking about his words.”

“Who was he?”

“I saw old Autumn in the misty morn stand shadowless like silence, listening to silence,” Dasha quoted, inviting him to talk, pretending not to have heard the colorless tone of his voice. “He wrote that two centuries ago. Isn’t it wonderful?”

“It is.” His hand slid down her waist, making her shiver. “How long have you been on a diet?”

“Oh, you’ve noticed it too! It’s a purely psychological thing. No diet at all.”

“Fat or thin, I like you no matter what.”

“I’m a shadow,” she said, lowering her voice.

“Uh-huh,” Stanislas answered.

Each of Dasha’s emotional stresses had a self-destroying quality to it. Her first love was a depressing Emo who always wore black and cut his wrists. Her second love was a married man who drank too much. And now Stanislas who was neither clever nor kind nor honest nor anything. She could see that but still she loved him desperately like a drowning man loves the straw he has managed to clutch.

They walked towards the arch. It was early spring; the nights were still cold, but several couples sat on benches, lurking in the shade. Small shadows sat on big shadows’ laps, looking happy but arrogant.

“I gotta go,” said Stanislas.

She touched his arm.

“Why?”

“Getting late.”

“No, not yet.”

“What difference does it make if you don’t say anything interesting? Do you think this is a conversation? Do you think we’re talking? I feel alone. I don’t want to be alone. I want to be with you; I want to take you to my place, buy a bottle of something, and have a really wild time.”

“No, my mother said…”

“The hell with your mother.” He hugged her. He was so big that she felt as if she was drowning in him. It was hard to breathe, then she stopped breathing altogether. Her back arched, and she felt refracted like a ray of light entering a prism. Her hips were pressed so hard against his that she was sort of oozing through her clothes like melting butter, or probably her tactile nerve endings had grown through the clothes and she could feel his body as if they were both naked. Her hands started stroking his back up and down, in reflex jerking motions, the way a dead frog moves when they cause its muscles contract with electricity. She still did not breathe. She just did not need to. She was out of her body and could do without it quite nicely, and her body could also do without her.

He leant away from her.

“You’re provoking me,” he said.

“Am I?” she asked, surprised.

The most provocative thing she had ever done was inserting a split infinitive into her creative essay.

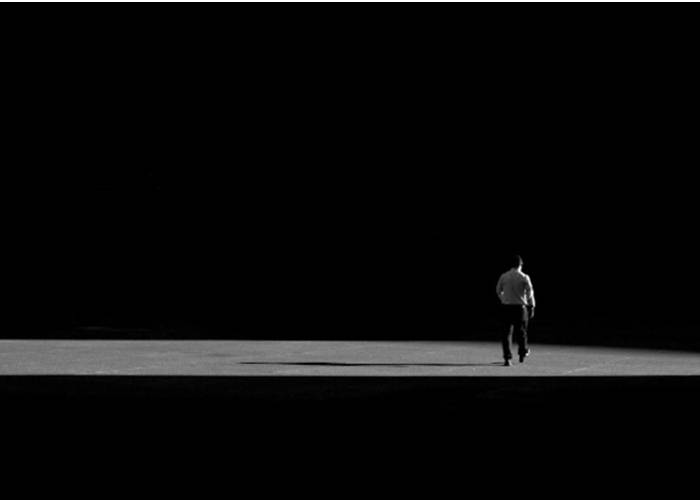

He said a cold good-bye, and started walking away along the alley. Chilled, she watched him. He strode confidently. He did not look back.

She closed her eyes. “Please, I want to stay with him,” she prayed, asking the vast and motionless spectator whose presence shimmered in the air, in the night as clear as icy cold water, someone who shaped everyone’s destiny and could work miracles, “Oh, please, please, pleeease, let me be with him! I want to be his girl, his dream, his wife, his plaything, his life, his forever after… I want to turn into his shadow.”

And then something happened. Her body was gone. The vertical sky moved rhythmically in time to someone’s steps. The world has changed: the rail-posts slithered by her very face; Stanislas’s back was ahead and above her. The poplars loomed backed by the stars.

I’m a shadow, Dasha thought. Oh, how fortunate, I’ve become his shadow.

*

A lonely lamppost illuminated the inside of a fragile green globe of first spring leaves. Dasha stretched out across the dark uneven asphalt. The ribbed wall of a playground refracted her shoulders and head. Stanislas lit a cigarette. The smoke was glimmering in the lamp light. He turned back. A look of mild surprise passed across his face. He shrugged and stepped forward. Dasha fell on an advertising board where an exuberant woman, crazy about a brand of yogurt, paraded all her thirty-two, or even more, teeth. Being very close to the man she loved, Dasha could clearly see his face, which looked indifferent now: Stanislas had already forgotten about her.

He threw the cigarette butt away, sniffed at his fingers, cursed quietly, walked through the arch, got on a bus. The bus was moving through the night, and Dasha, lying on a rubber floor mat as a shadow, was part of the big shadow beneath the chairs.

Stanislas climbed out of the bus and crossed the street. Dasha saw a car speeding to her. The next moment she flew up, slid onto the shining metal door, heard a compact burst of music, and fell into the darkness again.

There was a lamp in the elevator. Stanislas was very tall, but Dasha lay flat on the wall at her usual height. Now he was near. He’s mine, Dasha thought, from now on I’ll be always with him. She felt calm and tender.

At home, Stanislas took some soup from the fridge and started eating it cold. Dasha was watching his broad masculine back. A fat cat, black and orange, striped like a bumblebee, came out of the next room and smelled Dasha with evident disbelief. Shoo! Dasha thought. The cat scratched the floor and stretched itself out alongside her.

After supper, Stanislas was busy reading something on his laptop. A lamp cast his long shadow on the far wall and Dasha could not see exactly what he was doing. Suddenly the phone rang.

“I see,” Stanislas said. “At eleven? No, I didn’t. I don’t remember where. I just said good-bye and… No, she’s not here. Well, that’s nice! I don’t know.”

The telephone rang six times during the night. Stanislas did not turn the light on, so Dasha was half-asleep. She blended into the general darkness of the room. When the darkness broke away, Dasha settled herself on the blue-shadowed silk of the blanket, turning into several dark strips and a small patch at the pillow. Stanislas was breathing at her face. She could feel the weight of his hand. She inhaled his soothing smell.

At seven, there was a ring at the door, sharp and painful like a dentist’s bur. Stanislas sat up on the bed and suddenly moved away. With Dasha creeping behind, he walked to the front door. Dasha touched various things in the room with a housemaker’s touch, getting to know everything around, making the place familiar. The gray day was filtering in through the windows.

Dasha’s parents came in. Then her younger sister (Dasha called her Splinter) followed, the doctor, and two police officers. Splinter looked happy to have an excuse to shirk school.

A policeman looked behind the curtain, probably inclined to think that it was the best place for hiding the meatiest parts of chopped corpses. The other officer, a woman, sat down at the table and got ready to write. The bumblebee cat rubbed itself around her legs with the determination of an athlete running laps around the stadium tracks.

“Well, well, well,” said the policeman looking into the other room, “she is not here.”

“I live alone,” said Stanislas.

The policewoman started writing with a depressing air of concentration.

“When did you see Dasha Prosol for the last time?”

Stanislas answered. He sounded honest. The policeman watched him with a cinematic half-smile.

“So you invited her to come here last night?”

“Well, yes, but she said she had to go home. It was late. Then she left me, just left.”

“There are lots of people who saw everything.”

The people who saw everything were six boys and nine girls: the additional girl was sometimes sitting on a bench, just in case, acting as a safety device because spring is a dangerous time. None of them could say where Dasha had gone. Nobody saw her going out of the park either, but everyone saw Stanislas leaving the place alone. Someone saw him smoking, waiting, and boarding the bus.

Dasha’s clothes and her phone had been found in the morning. Her underclothes were encased perfectly within the outer garments. All the clothes lay precisely arranged, in the form of her body. But the body itself had disappeared. There was no blood on the asphalt. The police dog couldn’t pick up the trail.

“There’s something funny about it,” said the policewoman. “Turn the light on.”

Stanislas did it, and Dasha fell on the wall. The policewoman did not look surprised.

“There’s no need to worry,” she said to Dasha’s mother. “Your daughter has become his shadow.”

“But how can you be so sure?”

“Look at his shadow on the wall. It has long hair and breasts. Your daughter has been losing weight for days despite all the calories you’ve been feeding her, right? The process usually stars with an unexplainable weigh loss. It means you lose your substantiality. Then you just disappear.”

“Is it dangerous?” asked Mom.

“Not at all. It hardly ever lasts longer than days or weeks.”

“How could she do that to me?” asked Mom. “After everything I’ve done for her? How can I forgive her now?”

After that, Dasha was identified. The policeman brought a table lamp with an extension cord. He placed Stanislas by the wall and lit him at different angles. The lamplight glided over the brass door-handles and the Plexiglas on the desk. Dasha was examined closely and recognized. Her breasts served as conclusive evidence. The policeman took a few photographs of them.

“It’s not my fault,” Stanislas said, “she was always chasing me.”

“Wow!” said Splinter, checking out how strongly the cat’s tail was attached.

*

On Friday evening, Stanislas was invited to Dasha’s place, to dinner. The whole family was there; even the doctor came. Stanislas had flowers. Splinter invited two school-friends and brought a projection screen. “Let them stay here, please,” she pleaded, but it didn’t help: the screen was strung up behind the chair, but the two friends were banished immediately. There was a lamp on the edge of the table. Stanislas was squinting because the light from the lamp blinded him and hurt his eyes, and Dasha felt his pain like her own. She was a distinct image on the screen stretched along the x-axis.

Mom asked the doctor to give Dasha a check-up, hoping that the girl had solidified a little. She had not.

“Maybe, we should feed her?” said Mom and put a spoonful of rice to the screen.

But Dasha did not want to eat anything. Especially rice.

The supper dragged on decorously. Everyone except Splinter was very polite. Stanislas spoke slowly and weighed his words. He evidently wanted to please Mom, and Dasha’s heart throbbed with joy.

Stanislas went home at ten. Mom accompanied him to the gate.

“You can come again next Friday,” she said.

Stanislas was going away, and Dasha was stretching more and more. She bifurcated at every street-lamp, hopped onto the walls, rushed away from each car’s headlight.

Weeks crawled like centipedes, slowly moving their days: Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday. Stanislas did not buy flowers anymore and tried to leave earlier every Friday evening. Red-haired Marsha, or Marmoset, often phoned him to ask about Dasha. One day she came, took the reading-lamp in her hand, and examined the shadow on the wall. She agreed that Dasha’s figure was not bad, but on the other hand, it couldn’t even be compared to her own nice and slender build.

“Let’s check it out?” Stanislas said and gripped her buttock with the Neanderthal grace.

Marmoset pushed his hand away.

“Not in her presence, she’s my friend, after all.”

It turned out that Marsha was a true friend, and Dasha felt ashamed, because she used to call her Marmoset, and marmosets were not very intelligent creatures. Marmoset was definitely a more suitable name for her than Marsha.

One day Stanislas did not go to Dasha’s home. Mom phoned to ask him why. Stanislas said that he did not have time for it anymore. He had enough of it, he said. Dasha listened to him and cried. The shadow shivered on the wall.

He put the lamp behind his back and started talking to her. He was saying quite reasonable things.

“Look,” he said. “I can’t stand it anymore. I’m a man, which means I have my natural desires. There’s no way I can satisfy them because of you. You are not real, you are a shadow, and I can’t even touch you, to say nothing of sleeping with you. So I’m giving you a choice now: you can either turn back into a real girl and sleep with me as real girls do, or I’ll ask Marmoset to come, and she won’t refuse. Have no doubt about it.”

*

Marmoset arrived as quickly as if she could switch into fast-forward mode.

“Missed you so much,” she said. “What are we going to do about her?”

“About whom?”

“About that clown on the wall, of course.”

“If you can’t do it in the presence of your friend…”

“Of course, I can’t do it in the presence of my friend! But if she is such a bitch, she can’t be my friend anymore.”

Marmoset turned to Dasha.

“Get out of here! He told you he didn’t want to see you. Didn’t you?”

“I did,” lied Stanislas.

Marmoset gave him her most sugary smile.

“So why is she still here?”

Dasha couldn’t say anything. She just moved on the wall.

“Don’t squirm, just go,” Marmoset said. “Don’t you see you’re standing between us, between two loving hearts?”

Stanislas came to Marmoset and put his hand on her shoulder. For a short moment, his fingers played with her red hair like wind plays with a field of grain. She turned to him, pulled the lobe of his ear, bent him down, and kissed him, in order to dot the i’s. Stanislas was very tall. A real man.

“What are we going to do now?” she asked and slumped into an armchair.

“I don’t know,” said Stanislas, “Frankly, it’s killing me.”

Marmoset laughed.

“It’s killing you?” she said. “I hope you have some vodka. This liquid can make a crippled man walk and a blind man see.” She was sitting cross-legged, sexy, shaping the ideas in the air with quick staccato motions of her fingers. “And then, you know, we’ll just turn the light off.”

Dasha did not sleep that night. She was invisible and could not see, still she could hear voices, moans, rhythmic animal grunts, giggling, occasional swearing, ragged breathing.

The wall clock sang out two. Stanislas and Marmoset got tired of love and started cooing in soft voices like doves. Dasha was crying silently, diffused in the corners.

“Dasha, are you still here?” asked Marmoset.

“She can’t talk,” said Stanislas.

“But she can listen. Dasha, you should understand. He is not for you. You’re a good girl, you’re too good for him. There’s more IQ in your rear end than in his frontal lobe. You may hate me if you want, but, I’m saving you now. You’ve got a different destiny. You should study, then find a nerd for yourself, and forget Stanislas. He’s going to marry me.”

“Hey, I never agreed to that!” said Stanislas eagerly.

“What did you just say?”

“I said I’m not going to marry the first girl who jumped in bed with me. I don’t know you. Who the hell do you think you are?”

“Okay, then let me explain to you who I am. I’m not her, so I’ll never let you treat me like I’m nothing and get away with it. If you want to satisfy your natural desires, you must build a social unit. I’ve heard about it at a lecture.”

“And if I don’t want to build a social unit?”

“In that case, I’ll call my dad right now and ask him to come here. Consider this issue closed.”

When the clock sang out four, Marmoset said, “I wonder, is the bitch still here? Let’s turn the light on.”

Stanislas got out of the bed. The shadow was humbly hanging on the wall.

“No shit! This viper has not disappeared yet,” said Marmoset and cursed in words that would paralyze a rattlesnake, even an insensitive one.

I wish I were a viper, Dasha thought, I’d bite your pretty neck, and you’d be dead in a minute.

“Forget about her,” said Stanislas.

“No way!” Marmoset let the blanket slip off the bed. “If she wants to watch, let her see thev way a real woman should behave. Let her learn.”

She stood in front of him as naked and as dazzling as the sun. |

“How many guys have you slept with?” Stanislas asked her.

“Not many. You are my first true love.”

“Your pants are on fire.”

She laughed like a horse. “I’ve no pants on. Okay, my first time was when I was fifteen. I got really drunk and woke up in my friend’s house. With my underwear off. And I remember thinking that it was not important, anyway.”

“Was it your friend?”

“No, his big brother.” She laughed again, then made Stanislas put the lamp on the carpet, so that Dasha could see things better. Stanislas was amazingly obedient.

*

An hour later, Marmoset and Stanislas were hugging in the street. A yellow street lamp shone. Dasha was lying on the wet strip of bare ground pockmarked by high heels. It was about six: still dark, but the stars were getting pale.

“Do you love me?” Stanislas asked.

Marmoset’s eyes glazed over for a moment.

“Yep. You think I’d lift up my skirt for anyone?”

“Wouldn’t you?”

“Of course not,” said Marmoset. “Let’s close our eyes and count to ten, and maybe she’ll be gone. Honestly, she makes me uncomfortable.”

“Listen to the silence,” said Stanislas. “It’s so quiet.”

Marmoset listened. It was one of the infrequent moments of real silence around, when the soul feels how someone big sews seamlessly together the edges of yesterday and tomorrow. Small puddles reflected the flamingo-pink edge of the sky. She gave a weary sigh.

“My marmoset,” said Stanislas tenderly and kissed the crown of her head.

“Get your paws off of me, orangutan,” answered Marmoset with unexpected fury.

When they went back home, Stanislas had his former, masculine shadow.

The police visited them a few days later. Two policemen were looking for Dasha Prosol again. One of them even had a picture of the shadow made five weeks before.

For a moment, Marmoset regarded him with a smile no more friendly than a porcupine’s rear end.

“We don’t keep company with any slutty girls like her,” she said, having chosen the right kind of poison. “I am a soon-to-be-married woman, and this is my future husband.”

She gave Stanislas a resolute kiss on the cheek.

One of the policemen looked behind the curtain, but found nothing even there. Another one opened Dasha’s old lecture notes on literature.

“And I will show you something different from either your shadow at morning striding behind you or your shadow at evening rising to meet you; I will show you fear in a handful of dust. Eliot, 1922,” read the officer aloud. “What does it mean? Is it a threat?”

Stanislas creased his face into disciplined furrows. “I don’t get it,” he said. “I don’t read books.”

So they left empty-handed. Then Dasha’s father and mother came and asked Stanislas to return their daughter. Stanislas did not promise anything.

Dasha’s picture was shown on television. It was a photo from her yearbook. In it, Dasha Prosol held a carnation and a thick book. She was nice-looking and solid like a young champignon. She was looking down, decently. Then spring surged, real spring, with the sun and exams. Splinter shot up and thinned in no time. Mom shoveled rice into her, afraid that the story would repeat itself. But the bony Splinter was not going to turn into a shadow. She put on a most provocative skirt, painted her lips devilish deep magenta, and started cutting classes. Splinter turned Dasha’s room into an exclusive club for modern music fans. She wallpapered everything in the house with posters of bands, singers, and actors who had big guns and biceps.

Time was passing. Time was going by. Time was falling on everything like volcanic ash. Dasha Prosol became just a memory of the shadow. Marmoset got married to Stanislas, gave birth to a child, then got divorced, dumped the baby with her granny, and found a lover. Stanislas grew a beard and started working at a night club. He wore a uniform and looked impressive. Women loved him. They loved him like a cat loves meat because, you know, people are made of what they eat and what they read, and Stanislas who never read anything, was only what he ate.

*

Three years later the doctor was walking along a street of a strange town.

Suddenly he heard the quick clacking of heels behind him, and someone touched his shoulder. He turned back and saw Dasha. She was wearing dark glasses and gold ear-rings. She had dyed her hair.

The doctor stared at her in amazement.

“How do you do?” he asked unable to come up with a better question.

“You are always the same,” said Dasha Prosol and laughed, then became silent and looked very much like the photo from the yearbook.

“So, how’s your life?” he asked.

“Oh, just wonderful. The day before yesterday I came back from Australia.”

“Australia” was an abstract noun for the doctor, similar to “Austalopithecus,” a word he had learned in medical school, thirty-six years before. He knew theoretically that some people enjoyed distant voyages. He did not.

“And what about that boy, Stanislas?” he asked with pretended indifference, trying his best not to hurt her feelings.

“Which one?”

“That boy, who…” He paused, at a loss for words. He knew he was on thin ice.

“Oh, Stanislas, I forgot. As dead as a dodo. Thank goodness it wasn’t serious. Nothing special at all…”

She took off her sunglasses and met the doctor’s gaze. There was not even a shadow of recollection in her eyes; there was just a smile, quick and cold like winter sunlight sparkling off the water of a lake.

“How’s my family?” she asked, and something in her voice made the doctor feel empty and transient, as if he was watching a flock of birds flying over the autumn fields and feeling that the moment will never repeat itself. The Dasha he used to know did not exist anymore.

“Fine.”

“I’ll drop in some day,” she said and took a step away from him.

It was a clear summer morning. The shadows were bright and long. Dasha stopped and her shadow stopped too. It was the shadow of a man.

“Dasha,” said the doctor.

“What?”

“Who is it?”

The doctor pointed to the shadow.

“This one? Oh, well, just a nerd.”

And she walked away, and the shadow stumbled after her.