All chiseled, graceful, like a little flower, speaks powerfully:

“Do you want me to show you a secret place?”

And she takes me to the helipad.

The hospital where she and I worked at the time was in the Judean mountains. From the helipad, I could see the wooded tiers of slopes and a gap covered with sheaves of yellow bush and fig trees left over from the orchards of the villages that had once flourished there.

Under the precipice was a small ledge, and we descended to it and hid there from prying eyes, like children under the table at feast time.

The sun was going down in the gorge.

She closed her eyes and her swarthy skin lit up in bronze rays.

Another time, she said:

“Let’s go tomorrow and watch the Samaritans celebrate Passover.”

No sooner said than done, and we, who had been lost, almost ended up on the road to Nablus.

“It’s good for you,” she said. “They won’t do anything to you. You can say you’re a tourist. And they’ll eat me.”

“I’ll save you.”

“You will?”

But nothing happened to us on the outskirts of Nablus, we found our way and there we were at the Samaritans.

At the foot of an emerald mountain, on top of which were the ruins of an ancient temple, the village was crowded. Already at dusk, we went up to it with a crowd of tourists, who decided to gaze at the ancient ritual. Candles of blooming sea onions were ghostly white on the sides of the road.

The place was fenced off, the Samaritans unceremoniously screening the crowd at the entrance and allowing only locals in. I remembered how, as a boy in the suburbs of Moscow, I used to go with the boys to watch adult dances: the same fence, the same whirlwind, right up against the bars.

Sheep were herded from all sides to the shrine. New Mercs and Beamers drove up and parked, with dressed-up women and children clattering along the sidewalks on their heels, pulled into a special crowd separated from the place where the fire was blazing. The men had long since been in place.

Elders in fezzes and white robes were busily directing the action. They waved their staffs like the Maghribian sorcerers in A Thousand and One Nights, deftly feeding wood to altar fires in the great pits, sharpening long knives, and making other preparations. Some of the priests held books in their hands and read from them, swaying.

Near the fires, in the glow of the flames, bleating sheep swarmed.

At one point she whispered:

“Look carefully.”

I was already looking as hard as I could. Until the last, I could not believe what was about to happen. The fires in the pits spewed columns of sparks that outshone the stars.

A crowd of curious people clung to the fence, trying to grasp the meaning of the ritual.

The blazing darkness bleated, mooed and mumbled.

The shutters on the cameras chirped.

Suddenly something flew through the crowd, rushing and coming to a still.

All at once everything went silent.

Instantly the fires went out.

Silence covered the site, the village, the mountain, and the sky.

They killed them all at once, at a sign from an invisible conductor.

Silent was the death of many lambs.

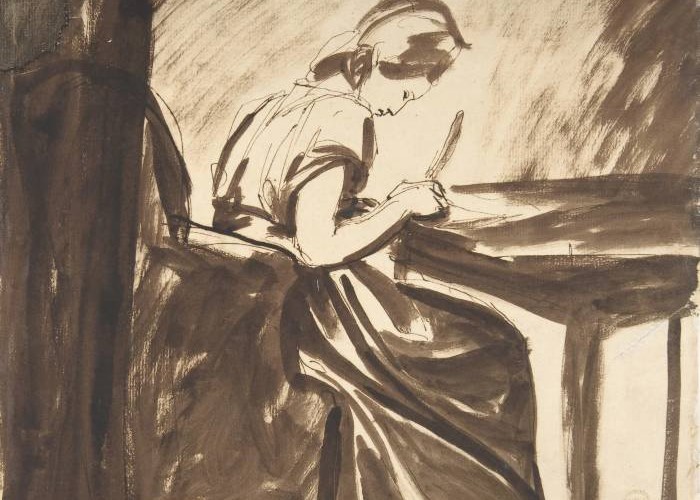

And when they were laying the freshly slaughtered carcasses on huge platters in the coals, when the quick, quick heat that remained from the edges filled the pits, deep as graves, she clung to me with her whole body and whispered:

“This is not my God.”

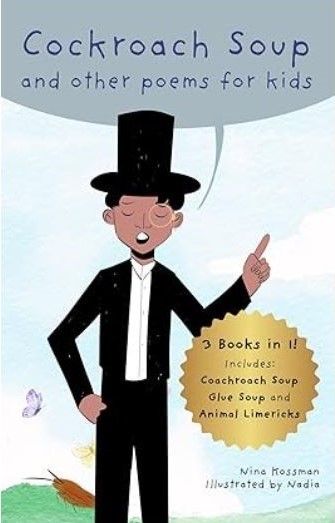

Translated from Russian by Nina Kossman