CHAPTER ONE. NOVEMBER 6, 1327 *

On Friday, November 27, 1327, in the cool early morning hours, an old couple with a little girl dressed in a dark blue hooded cloak with copper-colored curly hair, came out of a large stone house in the center of the “Old” Jewish Quarter of Zaragoza. The girl ran ahead of the old couple, sprinting ahead and back to them, as though urging them to hurry.

The girl’s name was Raquel, she was almost 11 years old, and like all children her age, she enjoyed every opportunity to get out of the house for a walk. Her huge blue eyes looked brightly at the world around her and a smile never left her happy face.

The elderly couple walking a few steps behind Raquel were her grandparents. They were in their fifties and looked quite youthful for their age. Don Leon Ohana, Raquel’s grandfather’s name, was taller than average, with fair skin and dark hair that now was mostly gray. He wore a dark cloak, almost knee-length and lined with wool, and his head was crowned with a strangely shaped hat that gave him away as a Jew. While in other parts of Spain, England, and France, Jews were required to wear a special mark on their clothing to distinguish them from Christians, in the kingdom of Aragon the laws were milder, and Jews were not required to wear yellow circles on their clothing. When it came to the formal observance of the rules, Zaragoza’s authorities looked the other way. The Jews of the city paid hefty taxes, held important positions in the county, and the kings of Aragon granted them certain privileges. Not wearing special signs on their clothes was one of them.

Donna Aina, little Raquel’s grandmother, was a beautiful statuesque woman. Like her husband, Don Leon, she had fair skin and beautiful brown eyes. Briefly, one could see how similar the grandmother and granddaughter were. Donna Aina wore a long burgundy colored robe trimmed with fur. Donna Aina’s hair was covered, according to the Jewish custom of the time, with a shawl. Complementing Grandmother Aina’s attire was a beautiful gold chain. More than once in her youth, Donna Aina’s aristocratic appearance attracted the attention of the Spanish grandees, and as she was leaving Juderia, the Jewish part of town, she always lowered her veil to hide her face from indiscreet glances.

Don Leon walked slowly, limping slightly, and leaning on a massive cane. He was thoughtful, and the only thing that took him out of his thoughts was the chirping of little Raquel and her constant questions. Don Leon was thinking about his upcoming meeting with the new King of Aragon, Alfonso IV. Don Leon had a very honorable but also a very thankless job of collecting taxes from the Jewish community and giving that money to the king. Although first Jewish settlers came here under the Romans, Jews settled in Zaragoza in large numbers in the 8th century, when the city was owned and ruled by the Arabs. Both under the Arabs and the Christian kings of Aragon, starting with Alfonso I, the “Liberator”, the Jews were well tolerated. Many of them occupied prominent positions at court and some Jews, such as Eleazar, became royal advisers to King Alfonso I. As a reward for their loyalty, intelligence, and honesty, some Jews were brought close to the king and were given vineyards, estates, and houses. And a select few were even exempted from paying taxes.

But Don Leon’s heart was still uneasy. He knew that the relative prosperity of the Jews in Zaragoza could come to an end at any moment. In 1294, then still a young man, Don Leon was going through one of the most terrible periods of his life. That year a rumor spread among the Christians of the city that the Jews had stolen a Christian boy and tore out his heart and liver for their magical experiments. That rumor put the Jews of the city in great danger. Fortunately, the Jews,and among them the young Leon, were able to find the missing boy alive and unharmed in a neighboring city. A bloody and merciless pogrom was averted.Zaragoza was one of the largest cities of Aragon and Castile, and in the 14th century, the city had more than 30,000 inhabitants, of whom about 10% were Jews.

It was a thriving community of artisans, merchants, builders, doctors, poets, financiers, and Talmudists. Walking through the streets of the Jewish quarter, Raquel recognized the streets by street signs. Here is Cobblers Street, here is Tailors Street, and here is Stonemasons Street. Like many Jewish children, even in the distant 14th century, Raquel could read. She read and wrote fluently in Spanish and Hebrew and, since her father and Don Leon’s house had books and maps in Arabic, she also learned to speak Arabic. In the 14th century, most scholarship, poetry, and philosophy were written in Arabic. The Jews who moved to Toledo and Zaragoza from Seville and Granada brought books, knowledge, and Arab culture with them to northern Spain.

After walking at a leisurely pace (because of a pain in his leg, Don Leon could not walk fast), they came out from the gate separating the Juderia (the Jewish quarter) from where the Christians lived and worked. In those relatively quiet days for the Jews of Zaragoza, many Jews not only kept their shops, offices, and workshops in the Christian quarter, they were even allowed to employ Christians.

Raquel, who had run a few steps ahead, turned towards her grandparents.

“Grandma,” Raquel pleaded pleadingly, “buy me something tasty!”

They were just passing numerous shops selling everything from nails and horseshoes to colorful fabrics and clay pots. But neither pots nor horseshoes interested Raquel at this point. Her attention was fixed on the rows of candied fruit, nuts, nougat, and marzipan.

Donna Aina lightly touched her husband’s sleeve. Don Leon happily took some maravedi out of a leather pouch and handed them to the girl. Raquel galloped off towards the benches. She returned with a large bundle of sweets, and a piece of sweet nougat hiding treacherously inside her cheek.

She took a canvas cloak off the little basket and generously handed the sweets to Don Leon and his wife. But instead of taking the sweets, the grandmother gently turned Raquel around and pointed to a skinny boy with a mud-stained face peering out of the forge. The boy was about the same age as Raquel, but he was so skinny that he could have been about eight or nine at most.

Raquel looked questioningly at her grandmother. Donna Aina smiled and nudged her granddaughter in the direction of the forge. Don Leon followed his granddaughter. Upon entering the smithy first, Don Leon turned to the blacksmith:

“Senor, will you allow me to treat your boy?”

Don Leon was wearing an expensive cloak, and the blacksmith quickly discerned a massive ring with a royal seal. Also, from beneath the cloak, the blacksmith could see the hilt of a short sword. In those cruel times, when human life was worth very little, such a ring with a royal seal and, of course, a sword served its owner as a letter of protection. The smith realized that the visitor was an important person, albeit a Jew. In the early to mid-14th century, individual Jews were not forbidden to bear arms.

Bowing before Don Leon, he said:

“Senor, my son, and I are at your service.”

Don Leon continued, “My granddaughter would very much like to share these sweets with your son and the other children. I hope you will not refuse her this little request?”

The blacksmith did not know what to say. All the while, the boy stood behind his father’s back. Tired of waiting, Donna Aina, went into the blacksmith’s shop. Raquel walked up to the boy and, smiling, handed him a basket of sweets.

The boy looked at his father, and the father permitted him, silently, with his eyes.

“May I ask your son’s name?” Don Leon continued.

“Diego, Your Grace,” answered the embarrassed blacksmith, hiding his black, calloused hands behind his back.

“Alonso, his father,” the blacksmith bowed, “always at your Grace’s service. Forgive me, Your Grace,” the father went on, “my boy is mute from birth; he hardly speaks, he only moos. My wife and I have tried everything, we took him to a witch doctor and the monastery of San Adrian de Sasave in Huesca. The local doctors refuse to treat him, and we have no money,” the father sighed. “It must be God’s will that he remain mute,” he finished sullenly. “Thank God he can at least hear,” he added.

“My dear Alonzo, I just remembered that I need your services very soon. I want to put bars on the windows and iron the door. These are troubled times. And you’re an experienced blacksmith. Here’s a deposit. Come next week. My house is in the Jewish quarter, we’ll show you around.” With these words, the elderly Jew handed the blacksmith a bag of money, and after petting the boy on the head, took his leave.

Donna Aina added, “We will gather things for your family and see what we can do to help the boy.”

Before Raquel stepped outside after her grandfather, the blacksmith’s son rushed to the back of the workshop and quickly returned with a small, palm-sized clay horse whistle and a small, almost toy-like, dagger, and scabbard. Without looking at Raquel, he handed her his gifts and hid behind his father’s broad back. Raquel took the gifts shyly, hugged the boy, blushed, and ran off to catch up with Don Leon. After saying goodbye to the blacksmith and his son, Dona Aina stepped outside.

After opening his leather pouch and counting the silver maravedis, the blacksmith Alonso scratched the back of his head and returned to his work. The money the rich Jew had paid him, the blacksmith thought, would be enough for almost the rest of the winter. His son Diego looked after Raquel for a long time, not daring to taste the sweets she had given him.

~~~

~~~

CHAPTER THREE. RAQUEL WANTS TO GO TO THE ROYAL CASTLE *

Eventually, Raquel and her grandparents made their way to Alfajeria. Raquel had never been to the palace, only seen it from afar, on those rare occasions when she went out of the Jewish Quarter with the grownups. In the morning, she begged her father to let her go into town, knowing that Don Leon was supposed to be at the palace at noon. And now, before the eyes of the 11-year-old girl, the royal castle emerged in all its beauty and grandeur. Raquel snuggled up to Donna Aina.

“Well, do you like it?” Grandmother asked.

“Yes, very much! I’d love to go there,” said Raquel.

“Little Jewish girls are not allowed in the palace,” said Don Leon. “Wait for me and Grandma at the Community House while we’re in the palace.”

“Grandfather, please take me with you! Tell the King that I’m your helper!” Raquel pleaded.

“My child, I’m afraid that’s not possible,” said Donna Aina softly.

“Grandma, don’t you want to see the King?”

“My little Raquel,” replied Donna Aina, “I have lived long enough to know that a king is a man like you or me, but with unlimited power and wealth”.

“A dangerous combination,” – Don Leon muttered, deep in thought.

“But I still want to go to the palace!” Raquel was stubborn.

Her wish was not destined to come true… if it were not for chance.

One of the guards guarding the entrance to the castle was a gentleman, whose name was Martin, who in the past was greatly helped by the son of Don Leon – Eugenio. Eugenio, Raquel’s father, was a doctor in a hospital in the Jewish quarter. And a few years ago, little Antonio, the son of Martin, the guard, became seriously ill. He had a high fever, and his body was covered with large blisters. The poor boy was delirious and did not recognize his parents and was fading before their eyes. Christian doctors refused to treat the boy, believing it was impossible to save him. The monks at the monastery hospital in Veruela admitted the poor boy, but they could not help him, promising to pray for the health of little Antonio. The little boy’s parents, desperate to save their son, brought him to the Jewish Quarter Hospital under cover of the night.

Eugenio, then a young doctor, returned from Padua, where he had been studying at the university for three years. On his return to Zaragoza, Eugenio brought with him an anatomical atlas and many medical books.

When little Antonio’s parents brought the boy in, it did not take long for Don Eugenio to make the diagnosis: the child had typhoid fever. Although there were almost no cures for this terrible disease, the young doctor made his own antipyretic concoctions and potions. Raquel’s mother, the beautiful Aster, cared for Antonio as if he were her own son. She made him thick chicken soup, gave him hot milk with honey, and when the boy fell asleep, she softly hummed the Jewish songs her parents sang to him. For two weeks, the boy’s sturdy body fought the terrible disease, but thanks to the care and medicines of Don Eugenio, Antonio survived. For almost three weeks, the child was in a Jewish hospital where he was visited by his parents, who did not believe to the end that Antonio would not die.

After three weeks, Antonio had made a full recovery and the boy’s father, Martin, came to take his recovered son home; he had no money to pay the hospital and Don Eugenio for his son’s treatment. Instead of money, he brought a bound manuscript and y handed the manuscript to the doctor.

“Señor, I brought this book back from when I was a soldier in the army of His Highness Prince Alfonso. We were badly beaten at the Battle of Lucosisterna in Sardinia. But we won, and I and my friends robbed the locals. You know how it is in every army. Don’t go home empty-handed. So, in addition to gold, silver, and stones, I took this book with me. I can barely read my own language, but it’s not even clear what’s written here.”

Eugenio took the ancient manuscript carefully and examined it for a while. After reading a few pages, the young doctor finally said:

“I cannot accept this priceless gift, my friend. It is the manuscript of Jacob ben Mahir ibn Tibbon, a famous scholar and physician.”

“Do not refuse me, doctor,” said the boy’s father politely and, returning the manuscript to the table, left the hospital with the boy.

Dr. Eugenio went deeper into reading the manuscript. For those times, all the advanced methods of treatment, operations, and anesthesia had been collected and systematized. The manuscript contained the invaluable experience of Arab and Jewish medicine over many centuries, written in Hebrew. And since then, this manuscript has become Dr. Eugenio’s board book, helping him save lives of many patients.

And so it happened that just on that day one of the guards at the gate was the same Martin whose son was saved by Dr. Eugenio. Martin saw Don Leon, in whom he immediately recognized the father of the doctor Eugenio.

As Don Leon approached the gates of the Alfajeria, he handed to the Head of the Guard (it was Martin) a piece of paper with the royal seal: an invitation of Don Leon to the palace to the king.

Seeing Donna Anna and Raquel standing in the distance, Martin asked:

“Señor, if I am not mistaken, the venerable Señora and the little beauty are the mother and daughter of Dr. Eugenio?”

“No, Señor, you are not mistaken. And I am Eugenio’s father. I was ordered to come to the palace to report to His Majesty King Alfonso. So, my wife and little Raquel volunteered to come with me.”

“May I see the King?” Raquel jumped out from behind Grandpa

“Señor Guardian, I want to go to the palace too…” Raquel looked at the guard Martin with a pleading look.

“Raquel, I have already told you that little Jewish girls are not allowed in the palace with the King.”

“Excuse me, Señor Martin, my granddaughter doesn’t know what she’s asking for- ”

“Well, at her age it’s only natural,” the guard laughed.

“And I think,” – he went on – “I think we could arrange it… now that I’m the Head of Palace Guards -”

“Come in, Señor,” with these words the guard signaled to open the gate and stepped aside to let Don Leon and Raquel through.

Don Leon looked at his wife.

“Don’t worry, Leon, I will wait for you at the Community House near the Great Synagogue on Koso Street.”

“And tell the King that you promised to be home for dinner,” she added playfully.

Raquel hugged Donna Aina and, holding her grandfather’s hand, walked through the wrought wood gate into the castle.

“Thank you, dear Sir,” said Raquel to good Martin.

“I won’t forget your kindness!”

“- and this is for your son,” – with these words Raquel gave away all the remaining sweets that her grandparents had bought her on their way to the palace.

The guard smiled: “Say hello to your parents and tell them that Antonio is alive and well.”

CHAPTER FOUR. RAQUEL IN THE PALACE *

After walking through the massive gate opened by Martin, grandfather and granddaughter found themselves in the courtyard of the castle. Despite the cold, trees and bushes were as green as in the summer.

“Over 200 years ago, this was the palace of Banu Huda, the Muslim ruler of Zaragoza,” Don Leon said quietly. “And,” he added, “the Arabs are superior masters of construction, all Andalusia was designed and built by them: canals, roads, bridges, cities, fortresses.”

“So, this beautiful palace, this fortress, and the garden, it was all built by them.”

Raquel walked, holding her grandfather’s hand, listening to his story. What she saw, instantly fascinated her.

In the park of the palace, richly dressed courtiers, monks in black or brown robes with huge crosses on their chests, were walking toward her. On the perimeter of the garden, at each door stood guards with swords, like their Martin the guard. Lavishly dressed ladies in long gowns conversed with men in armor. Each man had a sword on his belt and kept his hand on the hilt of the sword as he spoke. Servants scurried about among this group, silently doing their lords’ bidding. A few minstrels were playing their lutes and singing in the central alley of the park.

When she saw all this, the usually timid Raquel was stunned. She clutched at Don Leon’s arm and tried to hide behind his back.

“Let’s go home,” she whispered.

Grandpa squeezed her hand lightly and whispered back, just as softly. “Don’t be afraid, everything will be all right. Especially since,” he added jokingly, “it wasn’t the king who wanted to see you, but you wanted to see the king.”

The girl had never seen such luxury. What struck her the most was the singing of the minstrels — court musicians. She had never seen anything like this before. Neither in the Jewish quarter where her family lived, nor on the rare occasions when she went outside the Jewish quarter, had she seen either troubadours or minstrels. Strolling musicians in the narrow streets of the city and the squares of Zaragoza were nothing compared to what she now heard and saw at the King’s court.

Letting go of her grandfather’s hand as if mesmerized, Raquel stepped closer to the minstrels. Completely absorbed in the beautiful music, Raquel did not notice that people started to gather around her. It was not often that a Jewish child found herself at the court of the King of Aragon, and this could not fail to arouse the interest of the Aragon’s nobility. Even in those relatively prosperous times when Jews lived and worked side by side with both Christians and Arabs, Jews mostly lived separately and avoided close contact with members of other religions as much as possible. Seeing this, Don Leon hurried to get his granddaughter away from the crowd. But before he could do so, he heard the king’s courtiers – the noble hidalgos and their ladies – whispering, “What a pretty girl, pity she’s a Jew!”. As he approached one of the guards, Don Leon asked to be reported to His Majesty’s secretary. The guard returned and announced that the king would receive him soon.

Don Leon had intended to walk further into the park, where he would wait for an audience with the king, but his restless granddaughter dragged him towards the musicians. Leaving his grandfather to watch the musicians from a distance, Raquel walked quite close to them.

Three musicians, two with a viela and one with a lute, were playing a very beautiful and sad tune. Unexpectedly, Raquel began to sing, softly at first, and then more and more confidently. Gradually, the conversation around her died down and the king’s courtiers surrounded the girl. Raquel was so captivated by the beautiful music that she did not notice anything and continued to sing. Finally, the musicians finished playing, and the beautiful ladies and the caballeros clapped. And only then did Raquel notice that many spectators had gathered around her.

“Who are you, little one?” A young, beautiful woman asked Raquel.

Raquel was silent, and her grandfather came to her aid.

“Dear lady, this is my granddaughter, Raquel. His Majesty the King ordered me to come to the palace. My mischievous granddaughter begged me to take her with me, and I, out of my weakness, agreed,” Don Leon said, bowing to the lady of the court.

“If it was with her angelic voice that she begged you to take her along, no wonder you couldn’t refuse her.” The lady took off her precious pin and pinned it to the cloak she was wearing. “My name is Donna Maria, I am the King’s sister, but I would give anything for a voice like that!”

“But I have nothing to give you in return,” Raquel blushed, embarrassed.

Don Leon bowed and introduced himself. “Leon Ohana, His Majesty’s servant, and your servant, noble senora. I am the tax administrator of the Jewish community of the kingdom. At your service.”

“I’m sure your services and knowledge will be useful to my brother. He’s just coming to the throne, and the treasury, as always, is short of money. And as for decent and honest people, there are even fewer of them in the kingdom.” Donna Maria said. “Go to my brother and don’t worry about your granddaughter. She will stay with me!” With these words, the king’s sister led the confused Raquel away into the depths of the park.

_______________________________________________________________

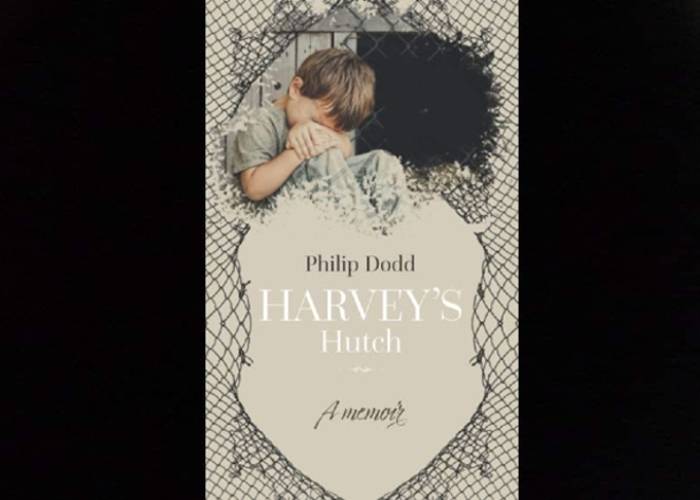

* The novel is set in the 14th century, in Zaragoza, the Kingdom of Aragon, where a large and prosperous Jewish community resided for centuries. The period is often called “the Golden Age” of Spanish Jewry, a time of tolerance when Jews were allowed to live peacefully with Christians and Muslims.

The novel is a story of a prominent Jewish family, with Raquel, a little girl, as the main character. Please note that only Chapters 1, 3, and 4 are published in EWLF. The novel is dedicated to the author’s granddaughter, also Raquel (Rachel).