For my grandfather, Yefim Vaynbein, with love, for continuing our family line.

Fima Vainbein was an intellectual intellectual—exactly in that order, just as written. He was a Doctor of Technical Sciences, a professor, and the head of the Machine Parts Department at a technical university. But that was only the official side of things. In reality, he was a man in the full bloom of his sixties, still sturdy, with a pair of slightly reddish, mischievous mustache, and a dark blue French beret—without a pom-pom, of course, because he was an observant Jew. He kept Shabbat, honored the holidays, and, when the occasion called for it (which it often did), indulged in a glass or two of inexpensive but quite decent red wine, which he picked up at the local German Lidl.

Germany had become his home in the late nineties—1997, to be exact, just as the year was drawing its last breath. The family barely had to wait for their invitation. Back then, Hessen was welcoming Jewish immigrants with open arms, processing applications in a month or even less. First, they were placed in a dormitory alongside Germans from Kazakhstan, in a town near a lake so clear and blue it could have been stolen from a postcard. But soon, fortune smiled, and they were given a three-room apartment in a four-story building in a tiny village called Niedenstein. It nestled in the hills like a well-kept secret, its air so pure that the village entrance bore a proud sign: Luftkurort—an air spa, a place where even the wind felt medicinal.

The hills surrounding the village were draped in a thick, whispering forest—ancient oaks with trunks wide as a man’s embrace, their canopies stretching like cathedral vaults. The air hummed with the scent of mushrooms, and along the clearings, wild raspberries and tangled rose hips grew in reckless abandon. The road from their home to the shopping center first cut through a wide field, flanked by a low wooden fence, then climbed gently toward the main street before taking a playful zigzag through a sparse patch of forest. And right there, almost hidden among the trees, lay an old Jewish cemetery.

Fima spotted it on his very first walk to the store. As always, he dragged along his faithful companion—a large wheeled shopping bag—into which he carefully packed the groceries from the list that his wife, Mira, had prepared. The list, it must be noted, never included red wine. That was Fima’s personal addition, purchased strictly for Shabbat, of course.

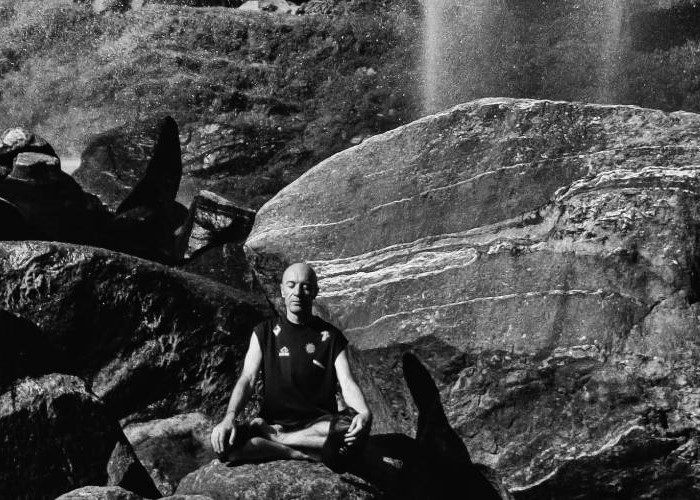

The first time he laid eyes on the cemetery, something inside him stirred. A call, a whisper—the pull of his ancestors. There was no logic to it, just an unspoken urge, a magnetic draw to step inside, to wander among the old, lopsided tombstones, to sit down somewhere in the hush of time and think. About life. About death. About the endless line of people before him, whose blood now flowed in his veins.

And so, the next time he passed by, he obeyed the call. Near the entrance, he found an ancient bench, its wooden slats tired and sagging. He sat down, reached into his bag, and pulled out the bottle of wine. He wasn’t particularly thirsty, but it felt right. Lifting it slightly, he nodded—to his brothers and sisters, to the forefathers and foremothers, to all those who had come before and might now rest beneath this very ground. Then he took a sip. And another. The silence around him deepened, thickened, wrapping him like an old, familiar shawl.

Only then did he truly look. And what he saw filled him with quiet sorrow. The cemetery was forgotten. Abandoned. Neglected. It had been a long, long time since anyone had come to visit.

And that, Fima thought, was not how things should be.

At home that evening, Fima did what any true scholar would—he dove into research. The internet told him that, before the war, Niedenstein had been home to around seven thousand people, nearly a third of whom were Jewish. Their fate was predictable and grim: concentration camps, shuttered businesses, desperate escapes from the Gestapo.

In the early 1940s, as the war raged on, plans had been made to erase the cemetery altogether—dig it up, reclaim the land for farming, and let the soil yield crops instead of memories. But the local sanitation authorities hesitated, fearing they would stir up disease. And so, it remained. Only the Hitler Youth, steeped in the Third Reich ideology, had dared to defile it, smashing dozens of gravestones in blind, brainwashed fury.

And that was how the cemetery had come to greet a Jewish man from Ukraine, who had, by fate’s peculiar hand, ended up in this quiet German village.

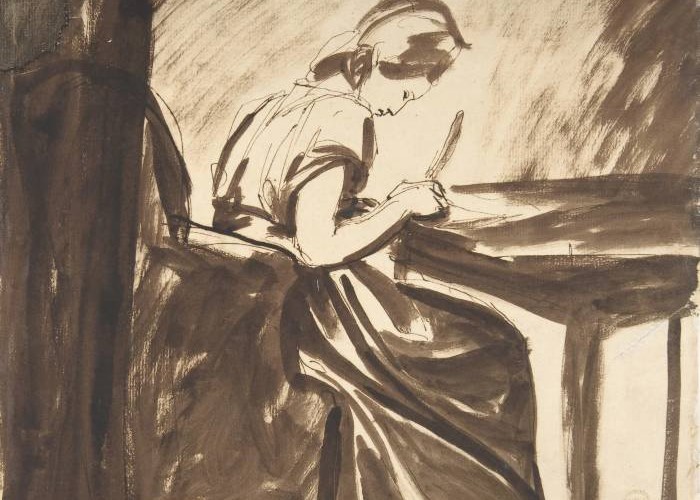

Fima began visiting often. Strolling among the forgotten graves, he devised what he called his “cemetery ritual.” He would clean a tombstone—pluck the weeds, sweep away the leaves, free the stone from the suffocating grip of time. Then, he would carefully write the name of the deceased in his notebook, sit on the old wooden bench, and recite the Mourner’s Kaddish. Finally, as was now tradition, he would take a sip of the inexpensive but adequate red wine from Lidl.

To properly equip himself, he returned to Lidl and purchased a small trowel, a rake with a telescopic handle, and a dustpan. Now he had a purpose. Three or four times a week, he would come to tend to his ancestors, fulfilling a duty he could not quite put into words.

Something in his heart ached at the thought of leaving “all of them” in such desolation.

With time, he even memorized the Kaddish, savoring the way the words rolled off his tongue. There was something profoundly holy in the act—the cleaning, the prayer, the sip of wine.

Fima had even memorized the memorial prayer by heart, and every time, he derived immense Divine pleasure from cleaning yet another grave, reading another prayer, and sipping from his flask of cheap red wine:

“Blessed is the Lord, the Blessed One, who grants me the ability to honor the memory of all those buried here” (he would say this on his own), then, as written in the Talmud: “May God remember the soul of my father, my teacher, my brother” (here he would read the name engraved on the gravestone) “Isaac, son of Samuel, who passed away on the second day of Shavuot in the year 692 according to the small count, who departed to the world beyond, in reward for my ability, without binding myself by an oath, to make donations for him and in his name. May his soul dwell in the eternal abode, among the souls of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah, and the souls of all the righteous men and women who are in Gan Eden (Paradise), and may his soul be forever bound to the Covenant of Life. Amen!”

At the end of this ritual, Fima would place a few small stones on the tombstone, walk to his bench, sit down, and sip from his small flask of cheap, yet tart, red wine, in memory of Isaac, son of Samuel.

This went on for quite some time—let’s say for about three months. When the spring floods began, Fima put his “cemetery story” on hold. “Let it warm up a bit, and I’ll come back,” he told himself. When the snowdrops bloomed in the forest, when the last patches of snow melted, when the nightingales began singing loudly in the mornings and the willows sparkled with their ripe buds, he returned to his work. By then, it had become the very purpose of his life there. He couldn’t do without it, and those who lay there couldn’t do without Fima. Of course, you might say this is nonsense—how could the dead not do without some Fima from Ukraine, even if he was a professor? But this is exactly how it was.

One day, after Fima had cleaned the grave of some righteous woman, Frau Kaiser, buried in 1932 on the 21st day of the month of Adar, he placed the stone, sat on his bench, tilted his unshaven face to the April sun, smiled, and just as he reached for his flask, he saw two minibuses pull up to the open gates of the cemetery. From them, a bunch of Jews, some in yarmulkes and some without, poured out. And it was quite possible that not all of them were Jewish, but they all had shovels, rakes, garbage bags, buckets, and some boxes. They rushed past Fima, shouting in German and Hebrew, and began sweeping, cleaning, pulling out weeds, taking out trash. Fima watched their work in awe, and for a moment, even jealousy crept into his mind—he had been there so long, and they, in one go, cleaned everything, finished up.

This continued for about three hours. Fima didn’t even notice how he drank his entire flask and began regretting that it was so small. When all these people finished their “work brigade,” they started coming up to Fima, shaking his hand, hugging him, patting him on the shoulder, smiling. One even kissed Fima on his unshaven cheek, which made him a bit uncomfortable, but he was simply in shock from what was happening, so he couldn’t respond. Besides, his German wasn’t great at the time, and the only word he knew in Hebrew was “Shalom.”

The last Jew, wearing a vest and a wide-brimmed hat, who was saying goodbye to Fima, took him by the arm and led him to the gate. He closed it, hung a large barn lock on it, and attached a printed sign in a plastic folder that read: “Entry to the cemetery by prior arrangement with the mayor of Nidenstein. Keys are there too. The only exception is Herr Fima from Ukraine, professor and doctor of sciences (for his services to the Jewish people, both the deceased and the living), or something like that, close enough to the truth…”

Feb. 8, 2025

___________________

Translated from Russian by the author