EXCERPTS FROM A NOVEL

“Kali mata! Kali mata! Kali mata!” A tall, thin old man with white hair that contrasted sharply with the black of his skin chanted the sacred mantras in a guttural voice and, with one blow of a large machete-like knife, severed the infant’s head. Blood gushed into a bowl made from a human skull. “Kali mata! Kali mata!” shouted the crowd, swaying rhythmically in a unified trance. “O Bovani, Mother of the World – this sacrifice is dedicated to you,” cried the white-haired old man, taking a sip of blood from the bowl and passing the sacred vessel to the next phasingara….

*

“Good evening, sir! Come into our workshop. The best fabrics, the most fashionable styles and very, very cheap. We have the best prices not only in Khaosan Road but in Bangkok. Where are you from? Ukraine? How is Mr. Klichko?” A short, stubby, curly-haired Indian, tried his best to lure passing Ukrainian tourists into the studio. Without much success, it must be said…..

*

The girls in this VIP salon, which had no signs or advertising, were exceptionally good-looking. Any one of them could have participated in the Miss Thailand contest and even won one of the prizes.

But the Thai general and the Indian politician were fully focused on their conversation and did not pay much attention to the members of the world’s oldest profession who were courting them. All in due time. Тheir turn would come, but first the most important thing had to be decided.

“Are you sure this will work?” A short, stubby Thai man in his forties once again questioned his interlocutor in broken English. He could have been mistaken for anyone, a middle-aged businessman, a taxi driver, or even a tuk-tuk driver, if it weren’t for his eyes. They gave him away. The eyes of a man who was not only used to commanding, but who would not be disturbed.

In appearance, the politician was the exact opposite of the general–a tall, big-bellied Indian with running eyes and scornful lips. He seemed amused by his interlocutor’s doubts:

“I’m sure, more than sure. Who was I before I met him?” he asked the general. He shrugged his shoulders, and the Indian continued: “A humble official of the magistrate’s office of the small town of Rekong Pio. Do you know such a town? Well, yes, how? No one does. And who am I now?” He would be a funny Indian peacock if it weren’t for his eyes. They reflected the darkness.

*

I walked toward the light. There was a fire on the shore. By the fire was an ordinary wooden table, filled with statuettes of various deities. And only in the center of the table was there a place free of statuettes. A naked infant was lying there. The Strangler himself was standing by the table with a machete in his hand. But where was his white hair? His skull was as bare as mine. Fucking conspirator.

The two throwing knives fell into my hands. I was ready to throw, and our eyes met. I was pressed to the ground like a stone. I couldn’t move, let alone throw the knives at the strangler. At the same time, he seemed to be struggling to keep me from doing anything. It was a standoff.

CHAPTER ONE

Bangkok – City of Celestials. Graveyard of the British Empire. From hell to paradise. A new investigation.

Do you love Bangkok as much as I do? No? You’ve never been to Bangkok? Or were you there for three days and didn’t like it? Or have you seen a movie about an assassin, starring Nicolas Cage, in which the city is described as murderous at the very beginning: “Bangkok! Corruption, filth, traffic jams!” And that’s not to say it’s not all here. Of course it is. And there are plenty of other things that make glamorous ladies, straitlaced men, and TV-fed bourgeois turn up their noses. Like any metropolis, Krungthep* has its underbelly. It was, is, and will be, but it is hardly fair to judge the city as a whole by it. It is different, terrible, and beautiful at the same time. And as far as I am concerned, there is a lot of beauty in it.

I fell in love with Bangkok at first sight. Maybe it was a set of circumstances. Maybe it was. I remember my introduction to the City of Gods. It was a dozen years ago. I flew to Thailand from Calcutta, which says a lot to a knowledgeable person. But to the uninformed, I’ll tell you.

It is hard to find a city in India that is as difficult for a European to navigate as Calcutta, also known as the Black Hole and the Graveyard of the British Empire. When traveling in this great country, one usually learns to ignore all sorts of inconveniences, be it dirty streets or the lack of the Indian concept of personal space. But Calcutta, which seems to have absorbed everything that can cause consternation in a European, can penetrate even the most seasoned traveler.

Claude Lévi-Strauss called it “the place of everything in the world worth hating. Nobel laureate Günter Grass, who lived in the city for several months, said of it: “It’s a pile of garbage that God has thrown away.” His local colleague and fellow Nobel laureate Vidyadhar Surajprasad Naipaul echoed him: “I know of no other city whose fate is so hopeless.”

Even when you are in the prosperous and, in some places, very beautiful city center, you can feel its gravity. I had only been to Calcutta once, for no more than a day, but that was enough to plunge me into hopelessness.

And so, after that little Indian hell, I found myself in Bangkok, which is the complete opposite of the former English capital of India. And as I rode into the city in a red and blue taxi on a sunny February afternoon to the music of the band “Endorphin” (I didn’t know who they were until later, of course, but the song was unforgettable at the time), I felt that at least I would have a romance with Bangkok. Later, it turned out that it was not a romance, but love. And I can’t say it’s one-sided. I often feel that the city responds to me in the same way.

I know for a fact that Bangkok’s goodwill won’t hurt me this time. The investigation here will not be easy for me. This is despite the fact that I gave up my job as an investigator for good (as I had thought recently) more than ten years ago. And even now, I didn’t want to take on this case. But… Firstly, it would be difficult to refuse the person who asked for a favor. And secondly, what is there to hide? I wanted to test myself: can I do it?

CHAPTER TWO

Knife fighting. The art of Kali. Aliens. An invitation you can’t refuse. Geologists and bards. The domesticated predator. A Soviet geologist’s lunch. The murder of a nephew. An offer you cannot refuse.

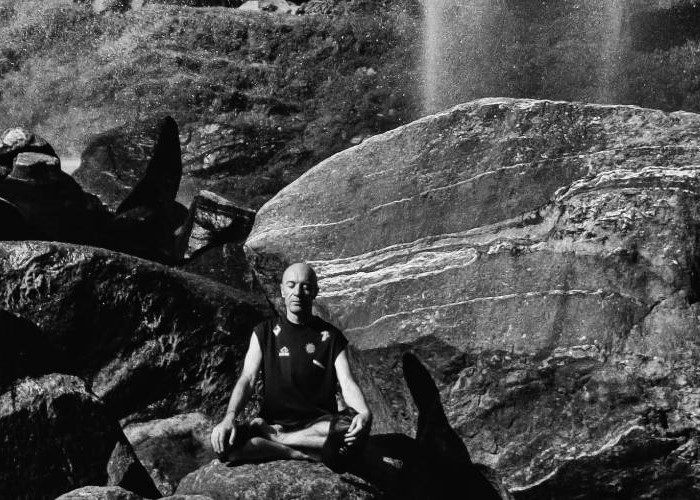

I was “pulled out” to meet this man immediately after the fight with Alexander Vesely. I had not yet had time not only to rest, but even to come out of the altered state of consciousness I usually enter before a serious fight. The fight was not easy. Sasha, despite his cheerful surname, was a very serious opponent, perhaps even one of the best knife-fighting specialists in the country. And I managed to beat him, it seems, only because he, not being well acquainted with Kali (a Philippine martial art characterised by refined techniques of close combat and knife fighting), underestimated me, and by the time he realized his mistake, it was too late. I myself understood all this very well, as well as the fact that I would have much less chance against him in the next fight. At the same time, I didn’t refuse the proposed new fight. Even if the chances of winning were small, if there was even the slightest chance, who said I couldn’t take it? Sometimes I think that this is what my teachers wanted to teach me most of all – the ability to seize every chance, even the smallest.

Just as Sasha and I shook hands and agreed to meet again, I was approached by this couple. I must say that the guys in our martial club, among a considerable number of masters from various schools, did not appear to be alien elements at all. Besides, they could prove themselves here if they wanted to. But they didn’t care, they were at work, and I was part of their work.

“Sergei Konstantinovich, can I talk to you for a moment?” asked the older man.

I hate being called by my first and middle name, but I guess that was their instruction, so I just nodded my head.

“We have a very delicate mission. Our boss, a very well-known man in the country, wants to meet with you about an important matter.”

“Does your boss have a surname?” I wasn’t being rude; I was just tired and wanted to get the ceremony over with.

“Yes,” replied the younger man. And gave his surname.

I whistled in surprise. This was serious. This man (let’s call him D) belonged to that cohort of businesspeople who are regularly invited to meetings by presidents and prime ministers. And what did he need from an ordinary private guide to various Asian countries? I’ve had occasional clients, let’s say wealthy ones, but people at D’s level usually travel differently. What does he want from me? I’ve asked his emissaries.

“He’ll tell you himself. We’re not authorized to do that.”

“I’ll have to go,” I thought. If I refused, I would die of curiosity and never know what D. wanted from me. And the boys were determined to get me at any cost. I had no desire to argue with them.

“OK. When and where?”

“Right now. We’ll take you there.”

An hour later, I was sitting at the same table with D. in the Geologist restaurant on Pertrovka, which is well known in small circles. Recently, there have been many such places of public catering in Kyiv, where nostalgia for the Soviet Union is played up—complete with an appropriate interior, menu, music, and a welcome to the past. And here at the table sat those who, in the past, had scattered the pieces of a huge country, because an ordinary person had nothing to do in this establishment – the price tag was too inhumane.

D. greeted me, not cordially (and why should he?), but rather in a businesslike manner, shook my hand and invited me to the table. I didn’t refuse a hundred grams of real Siberian tincture, and I didn’t refuse pine nuts, which are on every table in this place. For some time, D. asked me about the song of Vizbor*, sung by three men of taiga-bardic appearance, about Seryoga Sanin, who is so light under the sky. I answered him in the same way. But why study him? A master predator. Others rarely climb to such heights. Yes, he has manners. Yes, he’s been domesticated to a degree. Yes, he’s learned to control his emotions. But a tough, aggressive breed cannot be hidden from the scrutinizing eye.

“You’re probably wondering why I wanted to see you, aren’t you?” D. decided to cut to the chase.

I didn’t deny the obvious.

“The thing is, I really need the help of someone who doesn’t just know Thailand but knows it very well. And they say you’re one of the best. That’s the first reason. Secondly, this person should preferably have experience in law enforcement. And wow, there you go again.” When he saw that I was about to object, he gestured for me to stop and continued, “I know very well that you have been out of the business for a long time, but you used to have an excellent account. And I think your skills have not gone anywhere. So show them to me, of course, for more than a good reward.”

“Why don’t you tell me what’s wrong and I’ll tell you if I can help you or not?” I couldn’t accept the offer without knowing the details. I think D. has enough “knife and axe” workers for an outright felony, but we’re talking about something else here. But I’d like to know what it is before I agree. He’s a very dangerous man.

“Good.” D. stood up and gestured for me to follow him. We climbed into a helicopter standing in the middle of the hall, where lunch had been prepared for us. Two plates of buckwheat porridge, two cans of “Tourist’s Breakfast” and, of course, a carafe of blackberry tincture stood on an ordinary crate covered with newspaper. “But let us eat first.”

Why not? I like good food and good music. The singers in that restaurant were good. Very soulful. Yes, they have to entertain here those whose music is at best Leps and Stas Mikhailov*. But they did it with inspiration, putting their soul into the songs of the old days, singing more for themselves than for those who would not distinguish Vizbor from Gorodnitsky and Galich from Berkovsky*.

But I didn’t have to enjoy the Bard’s hits for long. Each minute of my interlocutor’s time cost less than a thousand dollars, and after he had eaten a little of the Soviet geologist’s lunch, he put the silverware aside and got down to business.

“You know, Serezha,” D. addressed me confidentially (or rather, pretended to do so), “this case is in many ways personal and quite painful for me, because a person close to me – my nephew – has died. He was murdered. His body was found a few days ago in a hotel in Bangkok. The police are, of course, figuratively digging up the ground to find the killer, but so far, no results. As far as I know, and as far as you know, as far as the police know, no clues have been found—no clues as to the motive for the murder. No witnesses. In short, as your former colleagues say, “a dead end.” But I have the feeling that somewhere inside the Thai police are missing something. Maybe a small thing, a small detail. And I want you to try to find what’s missing. And find out who did it. And then I’ll take care of it,” D. said the last words, and for a second, the real pain of losing a loved one and the mercilessness towards the one who did it, came to the surface. And then the mask fell back into place, and he continued, “I didn’t have much contact with my sister’s youngest son, but I liked Oleg. He was a smart guy, weird, of course, but who doesn’t have cockroaches in their head these days? Well, he wasn’t the worst. The kid just liked to travel the world by himself. He said it made it easier for him to immerse himself in another culture. Well, he did immerse himself.”

During the years of my own wanderings, which were often solitary, I met many such young people. I liked most of them for their attitude toward the world and their place in it. I am very skeptical about modern society, but these young people were an example that it still has a chance, and I have already spoken of chances.

D. and his people have calculated everything very well. First of all, it really hurts when very young people who are capable of bringing love and creativity into this world (that’s what Oleg seemed to be) are killed. And second, I had a similar case when I was working in law enforcement. I was prevented from solving that case because it affected the interests of those in power. In fact, that was one of the reasons I left my previous job. And here’s a similar case. And the personal interest of a powerful man makes it impossible to resign.

“I’ll try,” I said after a short pause. “Of course, I can’t guarantee the result, but I can promise you one thing: I’ll do my best.”

“That’s all you have to do,” D. said, “I’ll take care of all the financial costs, and everything you need for the case will be provided. All the information we have on the case will be given to you by my assistants,” D. nodded to the burly men I already knew. “When can you leave for Bangkok?”

“Tomorrow.” There was nothing to keep me in Kyiv, and I wanted to start the investigation as soon as possible.

D. glanced at his watch, indicating that the time allotted for this conversation was running out. He stood up, we shook hands, and D. exited the helicopter, walking to the exit of the hall. I moved to another table and began to study the documents and photographs that D.’s assistants had provided.

D. was right. It did look like a cold case. No clues. But my past experience told me it was never that simple. It was a good search, sure. But maybe they looked in the wrong place. Either way, we’d have to find out on the spot.

CHAPTER THREE

Khaosan is a mecca for backpackers. Police station. Lieutenant Supat Piukeu. Who strangled Oleg?

So here I am in Bangkok, making my way through the backpacker {backpackers are independent travelers whose budgets are relatively limited and whose backpacks can inspire holy awe in the average tourist} maelstrom of travelers along the iconic Khaosan Road. Once lost in the serpentine streets of the capital, Khaosan Road, once a haven for rice traders, blossomed after Leonard DiCaprio’s character from the movie The Beach walked it. Since then, to cross this not-so-long but significant street, you have to constantly dodge not only international youth of varying degrees of drunkenness and Thai girls of varying degrees of attractiveness, but also dozens of makashnitsa {mobile fryers} with all kinds of edible stuff, and loitering package tourists gawking at all this “Sodom and Gomorrah”. Hundreds of vendors smilingly lure you into their stalls. Hundreds of invitations to eat, drink, have fun, get a massage, buy something necessary, and something unnecessary.

A person unfamiliar with alternative lifestyles is often shocked to find themselves on Khaosan. There are a lot of people here. Punks, hippies, rastamans, artistic youth, musicians, artists, freaks of all kinds, and others about whom even I sometimes cannot say much. Khaosan is the Mecca of the free world, a hub for the New Age and Bob Marley, a world without borders on the planet and within the human consciousness. I can’t say I’m totally in love with the place. It has many things that belong to the underside of the city. But I embrace it, enjoy it, and watch it with curiosity – you can feel the pulse of the city here.

I prefer to live nearby. Not on Khaosan itself – it’s very noisy – but within walking distance, either on Soi Rambuttri or along the Chao Phraya River. It’s a good neighborhood, relatively quiet and with reasonable housing prices. It’s also in the historical center and within walking distance to a lot of great places in the city.

It is true that the place I am going to now can hardly be called wonderful. It’s a police station right next to Khaosan. For the policemen who work there, the area is quite hectic. Every tourist place attracts many people who are interested in taking money from foreigners. On the other hand, working in this area can significantly improve your financial situation. It is no secret that Thai policemen will cover anything that can be covered.

At 6:00 p.m., Lieutenant Supat Piukeu, who was investigating the circumstances of Oleg Ignatiev’s death (D.’s money and connections ensured me the most favorable treatment from the Thai police), was waiting for me at this police station. I hoped to learn something new from him that was not in the materials I had received in Kiev.

Oleg’s body was found in a room at the Grand Rambuttri Village Hotel. He flew from Jakarta to Bangkok on October 17 on an Air Agee flight. His body was discovered in the morning of October 20. A forensic examination determined that the time of death was around midnight on October 19. The passenger had been strangled. There were no footprints in the room. The perpetrator or perpetrators cleaned up thoroughly. There were also no clues about the stolen items. In any case, an expensive laptop, a digital camera and a cell phone, as well as a decent amount of cash, were left with the murdered man.

It was all very strange. Who would want to kill a guy? If they wanted to rob him, why didn’t they take anything? If the murder was committed during an argument in a state of passion, why no trace, which is usually the case. Someone destroyed all the evidence in cold blood. Looks like the murder was planned in advance.

CHAPTER FOUR

Acquaintance. Thai language. “My name is Sake.” Examination of the scene. A silver bracelet and a silver rupee.

Lieutenant Supat Piukeu was quite tall for a Thai, almost my height, and I was still 180 centimeters. He had a short haircut, sharp cheekbones, attentive eyes, and a classic Thai cordial smile.

I said hello to him in Thai and exchanged a few more polite phrases. The lieutenant asked if I spoke Thai. Alas, I had to disappoint him. I know only a few common phrases and prefer to communicate in English. Apparently, Supat, as well as many Thais with whom I had interacted before him, liked the fact that farang (that’s what Thais call white-skinned foreigners. It is not a disparaging or derogatory title) knows, even if only a little, his native language. His smile became even more sincere (which was evident from the wrinkles formed at the corners of his eyes), and he switched to English, which he spoke quite well.

I introduced myself as Sake. Thai people have a hard time pronouncing my name (there is no “g” sound in their language, and they are often too lazy to say “r”), so I prefer not to make them suffer. They pronounce my name Sake easily and correctly, and I have long since gotten used to it.

Supat didn’t tell me anything new. The search for the culprit was still unsuccessful. The entire hotel staff was questioned, everyone who could shed any light on the circumstances of the case. And nothing.

“Could I see the room where all this happened?” I asked the lieutenant. I felt I had to. And I was used to trusting my intuition in such cases.

“Wai note?” (“Why not?”) replied Supat, and off we went to the Grand Rambuttri Village Hotel.

I knew the hotel well. I had stayed there before. It is in a very convenient location on Rambuttri Lane (Soi), just a two-minute walk from Khaosan. Good rooms at a reasonable price, along with two rooftop pools. There were some minuses. Unusual for Thailand, for example, was the scolding of the service staff, which was easily explained by the large size of the hotel, a large flow of tourists and not the highest salary.

We walked to the hotel past several tailor shops (Indian callers offered to make a Versace suit for $100), travel agencies (Thai callers offered all kinds of tours in Thailand and neighboring countries), cafes, and restaurants with pleasant interiors serving Indian, Thai, and European cuisine. Nobody called anybody because there were enough visitors. The room on the second floor of the left wing was a classic double (a room for two, with a single bed for one). There are singles available in this hotel as well, but due to their cheapness and limited availability, they are almost always occupied, so even those traveling alone have to take a double.

The room hadn’t been cleaned since Oleg’s death; apparently, the police, hoping to find evidence, hadn’t given the okay to clean it. But evidence was scarce. I walked around the room and took a look. There were a few books on the small coffee table, a Lonely Planet guidebook (a popular series of guidebooks considered the best for independent travelers) to Thailand, and a stack of free maps of Bangkok, Chiang Mai, and other places. Among these papers was a photograph of Oleg, apparently taken in one of the temples in Bali. The pleasant-looking, blond, blue-eyed guy was pictured in traditional Indonesian clothing.

I thought it was very unfair to die at that age, just when the world is opening its arms to you. It’s sad. It’s very sad. I don’t like unfulfilled destinies. And that is what happened here.

And then, somewhere in my mind, there was a tiny little bird feeling that I was missing something important. I looked at the painting again. And I realized. Oleg was wearing a silver bracelet on his left arm in the shape of intertwined dragon bodies. And in the photos from the crime scene, this bracelet was not on his hand; I remembered it exactly. So it turns out that the killer did not take anything valuable, but took the bracelet, which is worth, maybe not a penny, but not so much. I wonder… What is this bracelet worth? Or is this trace a “nothing”? Maybe he lost it before or gave it to someone else? Anyway, it wouldn’t hurt to check it out.

I shared my thoughts with the lieutenant and asked him if Oleg’s other belongings had included a silver bracelet like this. He couldn’t remember, but promised to find out.

Meanwhile, I made my way to the bathroom. It was in perfect order, the kind of order you don’t find in a traveler’s room unless you have a severe form of neophilia. It looked like whoever killed Oleg had cleaned up after the crime. I took another look around the bathroom and was about to leave when I noticed a glint on the floor. I turned and took a closer look. There was a coin stuck sideways in the drain. It blended so naturally with the worn aluminum of the grated drain that it was no wonder no one had seen it. What was surprising was that I had noticed it.

I called out to Supat and pointed to the coin. With a magician’s gesture, he plucked a pair of tweezers from the air and carefully removed it. It was a silver Indian rupee from 1847.

CHAPTER FIVE

The Travel Guide Writers’ Mistake. In Love Restaurant. Sunset over Bangkok. An epiphany. Silver for silver. Strangler. Thugs. Phasingars. Men of the noose. Deceiver. Supat’s call.

This city is called the City of Angels. It’s funny that not only the guides, who get a lot of things wrong, but also the authors of travel guides say this. And for some reason nobody thinks about the fact that the word angel is a European, Christian word. And there are no angels in the Buddhist pantheon, no matter how you look for them. But there are many other beings that live in the sky, and so the correct translation is the city of heavenly beings.

In this city, I have not only my favorite places, but also my favorite restaurants. As a rule, there are almost no tourists in them, their customers are Thais and expats {expat – expatriate, farang, permanent resident of Thailand}. One such restaurant with the romantic name “In Love” is located on the bank of the Chao Praya River right at the pier “Rama Seventh Bridge”.

I sat down at a table on the open terrace on the second floor, ordered 50 grams of whiskey and soda, traditional Tom Yam Kung soup {a sour spicy soup with shrimp – the most popular dish of Thai cuisine} and no less conventional Khau Phad Kung (fried rice with shrimp) and thought. Somewhere inside me I already had the answer to the connection between the missing silver bracelet and the silver coin found in Oleg’s room. I just had to get it from there. It was easy to say, but how to do it?

But I have a signature method. You have to go from the mental level to another level for a while. For example, as my yogi friends say, “walk your astral body,” that is, try to get as much physical-sensual pleasure as possible. To that end, I wanted to have a good meal, a few drinks, and watch the sun set over the Chao Phraya River.

As the sun pulled the last orange specks from Bangkok’s billowing clouds, and my whiskey reminded me of itself with pleasant exhaustion throughout my body, I asked for the bill:

“Chek bin,” pliz {chek bin is a slightly modified “chek bil” – a popular request in Thailand to bring the bill},” I waved my hand at a group of waitresses who were animatedly discussing something.

The girl was smiling brightly as she answered the call. She shook her head so happily that the long silver earrings in her ears bumped into her cheeks a little, and she quickly tapped out the amount of my meal on the calculator. Something about her made me look at her again. Small, thin like most Thais, and those big, ridiculous earrings. Silver earrings. Silver bracelet. Silver coin. Silver for silver.

Tugi. The Phasingars. Men of the noose. Stranglers who take only one thing from their victims: silver.

The Tugas, or as they are also called, the Phasingars (“stranglers”). The sect of these worshippers of Kali* appeared in India in the Middle Ages. They murdered travelers not for profit, but as a peculiar ritual of worship to the fearsome goddess. For several centuries, the Tugi deceivers (the word “Tug” translates as “deceiver”) terrorized the inhabitants of central and eastern India, wiping out not only individual travelers but entire caravans. According to some accounts, they killed more than two million people, a number that seems simply unbelievable.

Because the Tugas were not just bandits from the Great Road, but religious fanatics, the authorities found it very difficult to deal with them. The sect was deeply secretive, and even their closest relatives did not know that their father, husband, son, nephew, etc. were Phasingars. If someone was caught, the strangler would not usually give up his comrades, preferring a painful death to betrayal.

Tugas would lure their victims to secluded places and attack them from behind, strangling them with a rumal – a sacred scarf that was a yellow silk ribbon about a meter long with a weight attached (to break the cartilage of the larynx more easily). The very process of killing by strangulation was connected with the fact that they were not allowed to shed human blood, except for especially important and terrible rituals.

There were also those among the travelers whom they had no right to strangle: Brahmans (priests), untouchables, pregnant women, children, people with all kinds of deformities, and representatives of those castes patronized by the goddess Kali, such as carpenters. If they got their hands on any booty, they could only donate it to the temple of the goddess Kali (and those who failed to do so were severely punished). Only silver objects and jewelry could be kept for themselves. If they got their hands on booty, they could only donate it to the temple of the goddess Kali (and those who did not were severely punished). Only silver objects and jewelry could be kept for themselves. When they accumulated quite a lot of them, the strangler was forced to cast a ritual hoe of silver.

The people of the noose terrorized India until about the middle of the nineteenth century, when the British managed to do away with them (well, almost). To do so, the colonizers used the harshest measures, stopping at nothing: torture, deception, and bribery. However, it is believed that there are no Tuggeros left in modern India, although many experts in the country have their doubts.

But here in Bangkok? Where from? If they are believed to be long gone in India, where would they come from here?

And what do we have to support this theory? Only my guesses and circumstantial evidence. First, the Tugas killed travelers. Second, silver rupees were usually used as the weight for the sacred rumala handkerchief with which they strangled their victims. And third, they had the right to take only silver as booty for themselves. But what would the same lieutenant say? He’d say it was nonsense, and maybe he’d be right. Maybe not.

And then my cell phone rang. “Speak of the devil,” I thought when I saw that it was Supat.

CHAPTER SIX

Adrenaline motorcycle taxi. Strangled farang. The passenger’s burden. Sukhvumit Soi 3 or the Arab Ghetto. Investigation of a murder scene. Cambodians under the Yabba. The art of Kali in action. Staying alive and being left behind.

And then my cell phone rang. “Speak of the devil,” I thought when I saw it was Supat.

“Can you go to our police station now?” He asked. “Something has happened.”

“I’ll be there in ten minutes,” I replied and left to find a motorcycle taxi. Of course, motorbike taxis are an adrenaline rush (they go very fast), but when there’s a traffic jam in the city, it’s almost the only way to get where you need to go on time.

As it turned out, my journey through the evening Bangkok on a motorized vehicle did not end there. The lieutenant was waiting for me in front of the police station, leaning against the 250-baht Tiger Boxer police motorcycle. The smile never seemed to leave his face. This time, however, it was a worried one.

He handed me a motorcycle helmet:

“We have to go to Sukhvumit Soi 3. The body of a strangled farang was found near a khlong. It’s not my area, but I don’t think it will be a problem to get information and examine the scene.”

Things seem to be moving quickly.

Supat turned out to be an even more daring and skillful driver than the motorcycle taxi driver who brought me to Khaosan. However, drivers of all kinds of vehicles saw a police motorcycle with flashing lights and a siren and immediately gave way to us. I have never traveled so fast in Bangkok. I have to say that I like to ride different motorcycles myself, especially in the mountains. But being a passenger is not the most pleasant thing to do, you can’t control anything, and you only rely on the skill of the driver.

Sukhvumit Soi 3 is an alleyway located almost opposite the fourth “soika” {soika – soi – alleyway}, which in turn is considered one of the most famous nightlife districts in Bangkok. This is where Na-na Plaza is located, where the go-go bars are concentrated. And therefore, the farang population in this area is always very, very high. The third “Soiku” is often referred to as the Arab Ghetto because of the large number of Middle Easterners who live here.

I’ll tell you a secret, I’m a terribly positive guy, but I have my flaws. One of them is my inherent selective chauvinism (moderate). Why selective? Because I love Asians, for example, and at the same time have no particular sympathy for Arabs, blacks, and Indians (which is somewhat paradoxical given my deep love of India). So the third Jay Sukhvumita is terra incognita for me.

But again, there was no way to explore the place as we passed a cluster of hotels, shops, bars and massage parlors and stopped at a small empty lot near the khlong. Several police cars were already parked nearby. We were allowed to enter the scene of the crime.

In fact, there was nothing left to investigate. The body of the victim had already been placed in a special plastic bag, and the place where the murder had taken place was being thoroughly examined by the police, who were crawling on the ground and illuminating everything around with powerful flashlights. But to all appearances, nothing of value could be found.

This was confirmed by the lieutenant. He had time to talk to his colleagues, and they told him that a few hours ago, three girls working at the Pritty Lady Bar in Na-na Plaza (oh, that’s musical Na-na), who were passing by this vacant lot, saw two men dragging what looked like a human body. The criminals, realizing they had been spotted, dropped their load and ran off in the direction of the Khlong. The girls could not get a good look at them; it was dark and the distance to them was decent. When the girls got closer, they realized it was the body of a farang and immediately called the police. According to the experts, a white man of medium build, about thirty-five years old, had been strangled with a kind of ligature.

I had no doubts. It’s close. But I could use some facts. And facts were in short supply. Nevertheless, I told Supat about my suspicion.

He took my story seriously. But like most people in the world, he knew little about Indian stranglers.

“Could you tell me about them?” He turned to me.

“Of course I can. But I’m not an expert on the subject either, so I’ll tell you what I know, which isn’t much,” I said, and began my story.

The lieutenant listened to me very attentively and at the end of my speech he said that he would take me to my hotel and then go to the archives to find information about the Tugas.

“Great,” I said and added: “Can you ask your colleagues who are investigating the murder of this farang to keep us informed? And can they find out if this guy had any silver jewelry?”

“I have already asked them for all this,” Supat replied.

Ten minutes later he dropped me off at my hotel and after wishing me “Ratri savat” (good night) he went to his station. I did not want to sleep, so I decided to take a walk to the river. I was crossing one of the khlongs on a narrow footbridge when two men came towards me. They were of medium height, black faces, eyes wide open (it looked like they were under yabba {yabba is a methamphetamine drug}) and holding impressive sized machetes.

Seven years ago, I might have been afraid. But after living in the family of the best Filipino martial arts master for three years and practicing Kali (Eskrima, Arnis) every day and night* for three years because of a mysterious story (maybe I’ll tell it someday), I wouldn’t be afraid of five Cambodians (and I realized right away that they weren’t Thais) with machetes. And although the guys were serious and did not want to see me alive, I had other plans. Too bad I couldn’t keep them both alive. There wasn’t enough room. The bridge was narrow, and there was no place for me to turn around. So I wisely placed one of them under my comrade’s machete and then took it myself. A few seconds and it was over. That’s a long fight in the movies. A real fight is short, unesthetic and scary

I’ve had to kill before. Then I was protecting other people from religious fanatics. Now I was protecting myself. If I had the chance, I would have let them live. I didn’t—another burden on my karma.

I called Supat, and five minutes later, several police cars pulled up at the bridge. A lieutenant got out of one.

“Looks like we won’t be separated today,” the lieutenant joked, his smile on his face a little inappropriately. – Are you all right?

“I am. I nodded at the dead bandit, but the other one is alive and almost well.” But the other one is alive and almost well. I’d like to know who told them to kill me.

“Maybe it was an attempted robbery?” Supat suggested.

“Do you believe what you are saying?” I asked him in turn. The lieutenant shrugged his shoulders and ordered his subordinates to take the live bandit to the station and keep an eye on him.

CHAPTER SEVEN

A real breakfast. Grandpa and Grandma’s. A feast of taste. Puzzles without clues. Patrons of stranglers. Calling D. Corresponding with a friend. Pandit Chidambaram. A ticket to Varanasi. Indian visa.

To get your day off to the right start in Bangkok, you need to start with a proper breakfast. What kind of breakfast? What is an American breakfast in a hotel? Let the Americans choke on their toast and bacon – that’s their way of eating. We’ll go the other way.

We’re going a little away from the tourist spots. In one of the quiet neighborhoods near the Dusit* district, there’s a Thai street café. I call it: “Grandpa and Grandma’s. They’re in charge. Everyone works there: children and grandchildren, but the representative functions are entrusted to the grandfather. He greets everyone with a hearty “Sawatdi khap” and demonstrates the dishes. He already recognizes me, and knowing that I only eat one dish, he orders me to bring fish in curry sauce. And I don’t just eat it, I make a feast for my taste buds. I have to say that curry sauce is very common throughout Asia, but in no other country, nowhere else, have I found it so suitable for me.

I had breakfast and thought about the events of the previous day and night. The apprehension of the bandit who attacked me was not the end of the matter. When Supat and I arrived at the police station, the Cambodian (and the police confirmed that Cambodians had attacked me) was already dead. Whether he had hung himself or had been helped was still to be determined. But it was already clear that someone in the lieutenant’s entourage was working for the mysterious criminals.

But there were many mysteries… How come the criminals who killed Oleg were never seen? How did they get into his room? Apparently, he let them in himself. It is clear that Tugi are first and foremost tricksters, but how did they gain his trust?

Why haven’t there been murders like this in Bangkok before? No, people have strangled their own kind here from time to time, just like in any other city. But nothing before that indicated a gangster. Almost all strangulation murders are domestic.

What’s the conclusion? And this is the conclusion: the criminals arrived here not too long ago and just started their ritual murders. Or maybe they were better at hiding what they’ve done in the past. It would make sense to ask Supat to look into the missing travelers. And also the Indians who came to Thailand from India in the last few months.

And one more thing. These aren’t just hit-and-run killers. As soon as someone came forward to suggest that they were stranglers, that person (i.e., me) was immediately targeted. The perpetrators have good cover. And at the highest levels. A very frustrating factor, I must say. It will be difficult not only to get to the truth, but also to bring the killers to justice. The latter, however, is no longer my task, but D’s.

Just as I was thinking about my employer, he called. I briefly told him about my suspicions. He asked if I needed security (apparently, he had already received information about the failed attempt on my life). I thanked him and said no. D. wished me good luck, and that was the end of our brief conversation.

I went back to my thoughts. There was one more important point. We needed more information on the stranglers. What I knew and what Supat had found would only be of interest to a fiction writer. We needed more details, more specifics.

I am not a big fan of technological progress, but in this case its fruits are to my advantage. Without leaving the cafe, I entered the information room. The person I needed was also on the Internet, but on the other side of the world.

I started the correspondence: ”Hi!”

”Hi,” Sasha replied.

Sasha is a good friend of mine, a traveler, a great expert on India. I have known him for a long time, and I realized that if anyone could help me learn something about stranglers, it would be him.

I typed the following sentence on my keyboard:

”What’s up? Where are you?”

”In Mexico. Visiting Alia’s relatives.”

Sasha met Alia, a Mexican dancer who became his wife, in the mountains of northern Thailand in the small town of Pae, a popular tourist destination.

”Great!” I continued.

”Where are you?” Sasha said.

”In Bangkok. I need your help.”

”Anything I can do to help–”

”I need to meet someone who has the most comprehensive information on Indian tuga stranglers.”

”Wow! Are you serious?” The smiley faces added to the text expressed my friend’s surprise.”

”Quite.”

”Where to meet? In Thailand?”

”That would be nice.”

”It won’t work. They don’t have people like that there. Go to India.”

”Okay! Do you know anyone?” I asked.

”Uh-huh. At the University of Varanasi*. Dr. Palaniappan Chidambaram. Give him my regards and I think he will help you.”

”Is there any way to contact him on the Internet, Skype?”

”I don’t think so. He is a classical pundit, committed to tradition. Memorizing the Vedas is for him, and computer work is for the youth.”

”You mean we have to go?”

”If it’s important to you, yes. By the way, why are you doing all this?”

”I’ll tell you sometime. And preferably in person. You’re not going to Mexico forever, are you?”

”I guess not.”

”Hope to see you soon then. Thanks a lot for your help!”

”Uh-huh. Good luck! And be careful with those phasing arrows,” Sasha said one last time.

Okay, I guess I should hit the road. I called Supat, told him what I was going to do, and asked him if he could make copies of all the documents on the case for me. He had no objection, on the contrary, he was sure it could help our investigation. We agreed to meet him at the station in half an hour. In that time, I had to decide how to get to Varanasi. As far as I knew, there were no direct flights from Bangkok to this most ancient city on earth, so I would have to change planes. And after all, it turned out that the most convenient option was to go via Kolkata.

I got the tickets quickly. Ten minutes and both tickets were in my pocket. The connection was convenient – only an hour and a half between flights. I left Bangkok in the evening and had to fly to Varanasi in the morning.

But that wasn’t the hardest part. Much more difficult, if not impossible, was getting an Indian visa in Bangkok in one day. But that’s if it’s legal. And if it is illegal, you can offer money to one of the consular officials. But this may not work – the money will be taken, and the result is not guaranteed. But if you pay the right person very well, then I think there will be no problem. But it’s not my job to find such a person and give him so much money that he can’t refuse. I called D. He listened to me and promised to do his best.

_____________________________

NOTES

Chapter One

*Kroonghthep is the abbreviated official name of the city. The full name is the longest city name in the world. It sounds like this: Krungthepmahanakkhon Amonrathanakosin Mahintharayutthaya Mahadilokpphonapharathatrathchathaniburirom Udomratchanivetmahan Amonphimanavatansathit Sakkathathattiyavitsanukamprasit. Translated all this means: “The City of the Sons of Heaven (Immortals), the Great City, the Throne of the Emerald Buddha, the Invulnerable City of Indra, the Great Capital of the World, endowed with the Nine Priceless Pearls, the Happy City abounding in Royal Palaces, resembling the Celestial Abode where the Reincarnated Gods reside, the City given by Indra and built by Vishnukarma.

*City of Angels – The popular press and some travel guides often refer to Bangkok as the City of Angels, which, in my opinion, is completely unjustified. It is more accurate to call it the City of Heavenly Beings (because, according to Buddhist mythology, there are not only those beings that correspond to angels, but many others who live in the sky).

Chapter Two

*Vizbor – Soviet bard

*Leps and Stas Mikhailov – Russian pop singers, favorites of the uncultured public

*Vizbor from Gorodnitsky and Galich from Berkovsky – Soviet bards

Chapter Six

*Khlongs are a network of canals that encircle Bangkok. In the past, when they were much more numerous, Bangkok was called the Venice of Southeast Asia. Many khlongs have been filled in for the simple reason that the land in the city center is highly valuable.

*I practiced Kali nightly – I remember Angel taking me to a river at night and saying, “Your job is to cross to the other side. I didn’t want to go into that river, which was full of snakes and crocodiles, even during the day, but at night. But I had to. I still have scars from crocodile teeth on my left leg, and a local antidote neutralized three snake bites. And how many gray hairs I got that night (I still had hair then)….

Chapter Seven

*Dusit is an area of Bangkok that houses the royal palace complex, the Throne Hall, and the country’s most important administrative offices.

*The University of Varanasi is one of the finest institutions of higher learning in India. It was founded in 1916.

*Pandit is a Sanskrit term meaning “scholar”. It means a learned Brahman.

*The Vedas are an ancient collection of sacred texts of Hinduism. The four main Vedas are the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Atharhaveda, and the Somaveda. They have been passed down orally since ancient times. Among the adherents of the tradition, such transmission of these texts continues today.

_______________________

Translated from Russian by the author