In a gesture of solidarity with Great Britain’s vulnerable Muslim minority I recently visited a Moroccan bar located in the basement of a restaurant near my home in Belsize Park. The restaurant itself is best avoided. The stake here is on the penchant of fashionably bohemian Londoners for eastern exotica: chairs of twisted iron (impossible to sit on), sculpted candles in a variety of colours and other decorative bits and bobs, and very decent – but extremely expensive – food, like Moroccan couscous with lamb shoulder joint, leg or other animal parts. The legs and thighs that draw visitors to the downstairs bar are not of the couscous variety, however.

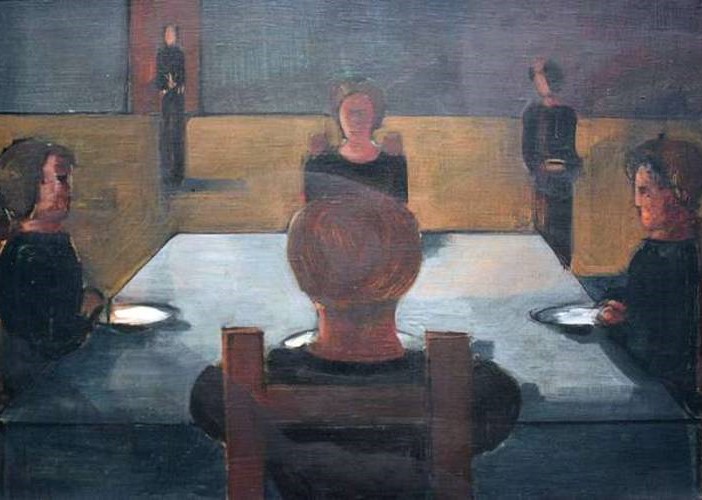

Officially the bar is open until one in the morning; in reality it rarely closes much before dawn. I had long been attracted by the unusual music emanating from it: something like the call of the muezzin blended with female contralto variations underscored by rock rhythms – in a word, Islamic rock ‘n roll. When I descended the staircase leading to the bar, solidarity with the Muslim minority was at its peak. Among the sofas and cushions of a far corner a young girl punk in torn jeans was performing a belly dance, egged on by the rhythmic clapping of an ethnically mixed crowd. I took in the scene from the vantage point of the bar, where I ordered my usual: vodka on ice with two lime eighths, which I squeeze out and drop in the vodka. My drink attracted the attention of the middle-eastern-looking man next to me; out of curiosity he ordered the same. He liked it. We ordered another round.

A conversation ensued from which it emerged that my interlocutor was an Iraqi émigré. In outward appearance he resembled a small shopkeeper from that region: outsized potbelly, fleshy nose, permanent stubble. Yet, strictures of Islam aside, his manner of consuming vodka was that of an old hand. In response to my comment he joked that it was wine Mohammed had outlawed, while the Koran made no mention of vodka. Not mentioned – therefore permitted.

Not long before my visit to the Moroccan bar I had chanced to watch a television documentary about Baghdad and the Iraqi intelligentsia. I was expecting something along the lines of Saudi Arabia, where hands are chopped off for petty theft, and public floggings are meted out for a shot of vodka. Not a bit of it. What I saw was far more akin to Moscow of the Brezhnev era: cafes nestling among enormous prefab housing estates, cavernous, smoke-filled apartments, noisy kitchen-table soirees of dissident intellectuals arguing over coffee-table tomes on Picasso and Bosch and exchanging Camus and Sartre novels. I was delighted by these analogies, so laden with nostalgia, in the geography and epochs of disparate countries and peoples. I liked the ease with which I could now hit upon a common language with an ordinary representative of the Muslim world and how clever I was in my mentioning, during our brief encounter, the sensation of political ambivalence that pervades life under the dictatorial eastern regime whose subjects spend their lives craving Western inner freedom.In this, I said, Saddam Hussein’s Baghdad was not that different from Brezhnev’s Moscow.

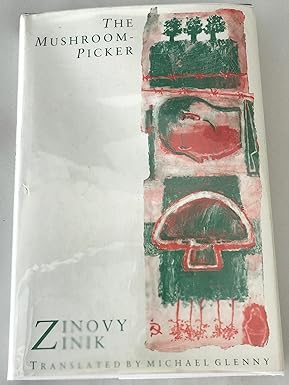

My interlocutor eagerly seized upon my train of thought: “Yes, yes!” he cried, “baktyn, baktyn!” I took the word “baktyn”, with the stress on the “a”, for an affirmative Arabic interjection, something along the lines of a “quite right!” or “precisely, old chap!”. Developing my thought further, he said that it was precisely this mirror-like ambivalence of the East in the Russian West and the West in the Iraqi East that accounted for the popularity of “baktyn” in translation among the Iraqi intelligentsia.

“Ahem… who?”

“Baktyn,” repeated my interlocutor. “Mikhail Baktyn.”

I began to blush, slowly and inexorably. The realization struck that this man, whom I had taken for an Iraqi shopkeeper, was referring to Mikhail Bakhtin, legendary Russian philologist of the 1930s and creator of the philosophy of carnival and ambivalence between rulers and ruled in street art. It turned out that I was talking to Iraq’s leading academic in the field of Russian philosophy and its chief translator of Mikhail Bakhtin. Like many Iraqi intellectuals, he had managed to make it to Moscow in the 1960s and on to the West, to London, in the 70s (we would have arrived at roughly the same time). He had passed through the same schooling in Russian intellectual vodka-shot chitchat as I myself had.

In parting he informed me that the bar’s music was not remotely Islamic, but actually rock variations on traditional Algerian Jewish melodies. The establishment, it transpired, was owned by Israelis of Moroccan extraction. Since my visit I have heard that it has gone out of business.

Translated from Russian by Ben Juda and the author.