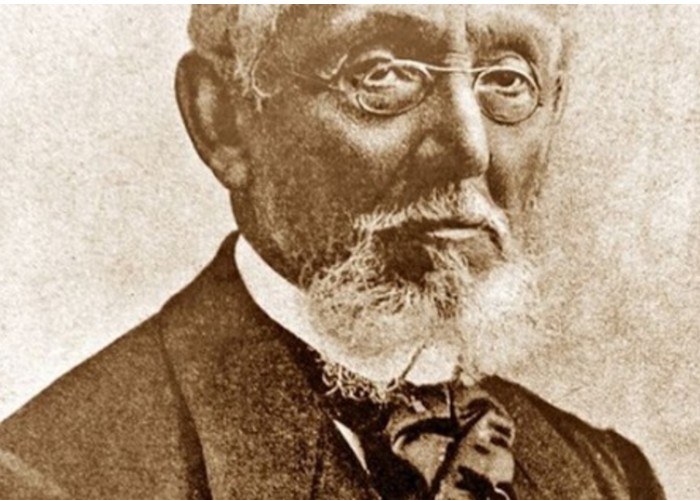

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born 163 years today, January 29, 1860.

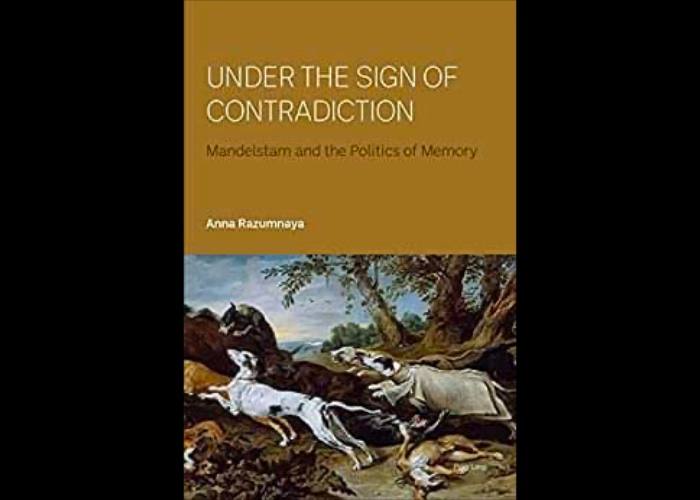

For Chekhov’s 160th birthday, Literaturnaya published an article about him, with Fedin’s words about talent gifting hope in the center of the text. In his commentary on Recaptured Youth, Zoshchenko also tried to clear Chekhov of accusations of “motives of melancholy, despondency, and tragic dissatisfaction”: Chekhov was in fact “cheerful, people-loving, hated any injustice, lies, violence, falsehood” – as if it were possible to hate injustice, lies, violence, falsehood and still love people who incessantly create all this, and continue to be cheerful (which Zoshchenko himself never succeeded in doing). Shestov was much closer to the truth: “Chekhov was a singer of hopelessness,” “Chekhov did only one thing: in one way or another he killed people’s hopes. And yet, children of so many nations would not be reading Chekhov if he did not bring them some kind of comfort. Which I would define as the aestheticization of powerlessness.

At our school arts soirées, especially against the background of poetry, which was perceived as an inevitable evil that had fallen on our heads for who knows what sins, the hilarious Chekhov was always received in triumph: “Fat and Thin,” “The Chameleon,” “A Horsey Name”…

But once, in a student dormitory when I was almost eighteen years old, I discovered “A Boring Story,” and I marveled at the yet unseen restrained nobility and incomprehensible beauty, which today I would rather call poetry. And by the time the muse began to appear to me, I had already idolized the sad intellectual in pince-nez to such an extent that his work seemed to me simply “the end of literature”. It seemed to me that there was nothing more to seek – neither exceptional events, nor great characters were needed, and all the drama of life could be conveyed without leaving the commonplace, without resorting to either stylistic tension or large-scale philosophy: just restraint, just subtext…

Sarcastic remarks by other greats about Chekhov bounced off me like peas off a wall. Tolstoy noted in his diary that Chekhov’s superiority over his characters is imaginary, that he knows no more than they do – well, so what? Chekhov discovered the most important thing: there are no trifles in the world; everything in the world is filled with significance as long as you look into it and tell it in Chekhov’s exact and ascetic language. In that romantic era, when young people were stuck on Hemingway’s subtexts, discovering that the most trifling dialogue fills them with mysterious depth when placed in a story, just as any object or even a spot becomes, when framed, a profound hint of who knows what — all of this was, for me, only an echo of Chekhov. (Yet Hemingway himself, who called Chekhov a clever doctor, did not mention any of his subtexts. Perhaps they were not so prominent in the translation?)

Although it was impossible to look down on Tolstoy, yet the refined natures of the Silver Age to evoke a condescending attitude in this reader – who did they think they were aiming at, poor souls! I have read Innokenty Annensky’s invectives with some sympathy for their author: did Russian literature have to sink into the swamps of Dostoevsky and cut down centuries-old trees with Tolstoy, in order to become the owner of this garden? Chekhov, according to Annensky, did not like anything but fresh milk and marmalade… Akhmatova with her absolute regality aroused rather an irritation, moderated by condescension to her lady-like infantilism – Chekhov’s world was grey and boring, it had neither sunshine, nor the clanging of swords – true, as a child, I liked Walter Scott with his countless swords, but now that we’re all adults, we understand that in today’s world, in our northern climate… – what do any swords or any special sunshine have to do with anything?

At that time I did not need either sunshine or swords, because I was intoxicated by my youthful chimeras and constantly dwelled amid the glitter and ringing. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky shook me too much and aroused too many feelings and thoughts to let me to mourn elegiacally. Paustovsky, my favorite, revealed the world as a beautiful romantic adventure – that’s what he seemed to me. While to complain of boredom and miserliness of being, when you practically do not know what boredom is, nor feel miserable for a minute – this exquisite coquetry was quite sweet! Yes, yes, the intoxicationwith with Chekhov’s sadness was real coquetry: it is quite pleasant to listen to a blizzard outside while staying warm.

But as one approaches old age, a sense of the frailty of all earthly things begins to haunt one seriously, there is no time for coquetry. When the feeling of insignificance of existence comes up too close, you can no longer hide behind Chekhov and it is time to reach for those romantic swords glittering under the midday sun…

Simply put, in my eyes, Chekhov ceased to cope with existential protection, the protection of man from the feeling of his own temporality and evanescence, which I now consider to be the first duty of art. Yes, of course, he sympathizes with us, this good Dr. Aibolit, he grieves with us, he condemns our abusers – but even the most hopeless patient would rather have medicine than sympathy from his medical staff! Likewise, I have begun to prefer books that awaken my pride and fearlessness rather than sad impotence: “Hadji Murat,” “The Old Man and the Sea,” rather than “A Boring Story” or “The Black Monk”. That’s when I began to hone my tooth for Chekhov – he had obscured the sky for me for too long. Unwittingly, he led me away from large-scale events to mundane minutiae, as if all the poetry and all the cruelty of the world were concentrated in everyday life – rather than heating it up in an artistic frying pan, as, say, Faulkner does.

But – Chekhov’s passionate admirers object – by depicting the everyday cruelty, which is almost imperceptible to the outsider’s eye, Chekhov awakens an aversion to narcissistic egotism – which might result in some of us taking a harder look at ourselves after reading, say, the typically Chekhov-inspired story “The Duchess. A young woman, who feels like a touching little bird, insults and harasses everyone around her, and when the doctor who has offended her etells the bitter truth to her face, she only hides in tears. One would hope that having seen herself in this mirror, the world will be made kinder.

Kinder… And then what? The father of the offended doctor – and his grandfather even more so – would have been whipped in the stable, without any explanation, if they dared to complain about anything to the ancestors of this duchess-bird. And they would sooner forget their humiliation than the doctor would forget his, whichwould be almost invisible to them, for no matter how much life improves, our demands on it grow even faster. If rudeness were to disappear from our relations altogether, if everyone only smiled at each other, we would begin to be hurt by a smile that was not wide enough or not sincere enough.

No kindness can protect us from the meaninglessness of existence: any scratch can kill a person with a weakened immune system, and it is hopeless to build a world in which nothing can hurt us. Empowering a person to endure mental wounds is far more important than removing sharp objects from their environment while increasing their vulnerability. Strength comes only from an exciting passion, an exciting goal, from the heights where everyday insults and failures begin to seem less important. Some twenty or twenty-five years ago, I was riding in a train from Peterhof with an acquaintance, a professor of mathematics, an excellent specialist, though by no means a genius, who was on his way to a hospital to have a neurosurgery, and throughout the whole ride, he was speaking with great excitement that one should not look at random processes this way, that one should look at them that way. I was glad for him, assuming that, if he was able to worry so much about small things on the way to the surgery, the operation was apparently not very serious, yet a few months later he was gone. On the other hand, the hero of “A Boring Story,” an eminent scientist who is on a friendly footing with Pirogov, in all his sad reflections does not mention science nearly once. He does mention something it very generally – but it is specific problems that captivate scientists!

And I realized then that what saves people is passion, excitement, which hides from them the futility and horror of being. And Chekhov’s heroes never had any goal for which it was worth exerting oneself, risking failure and humiliation. And so they would be doomed to ennui and emptiness, even if surrounded by superhuman kindness and delicacy: without an absorbing goal, it is impossible to be either strong or happy.

It has long been commonplace that Chekhov portrayed all of Russia. He has, in fact, as at Uncle Yakov’s, enough stuff about everyone – officials, peasants, landowners, actors, prostitutes, artists, engineers, but none of them is happy, none is involved in his work (except perhaps such weirdos as Dymov, while strong, smart, proud people are forbidden in Chekhov’s world). Even the artist Ryabovsky utters nothing but platitudes. All right, he was no Levitan, whose tears began to roll as soon as he saw hoarfrost on the glass or an autumn road (Korovin, who went to study with him, was always mocking him), but still, Ryabovsky was capable of painting “really splendid” pictures, he had experienced truly high moments, just as he had experienced many hours and years of hard work – why should he be depicted only in his moments of decline when Apollo was no no longer calling him to the lyre, so to speak?

Chekhov was a younger contemporary of the titans of the People’s Will, but the dreams of the people came into his world only as parody of vulgar or moody sourpusses. Perhaps, to a sober eye, they deserve nothing better, but it seems impossible not to admire the will – not the People’s will, but the human will. (Pushkin, by the way, perfectly understood the difference between the artist’s view and the politician’s view: it’s all fine poetically, but they must be crushed, he wrote about the rebel Poles.) And if there is a terrorist in Chekhov’s “Tale of an Unknown Man,” it is, of course, a disillusioned one. In my youth I worshipped these truly heroic figures, and when I reread the memoirs of those who, for whatever reason, were not hanged – Morozov, Figner… – I found that, after decades in prison, they didn’t show the slightest sign of disappointment in their earlier exploits. Yes, there was also Tikhomirov, but his way to disappointment in the revolution was a path of painful struggle, his diaries at times shock with the essence of pain and loneliness in a foreign land: “realist”, he is suddenly pierced by forgotten smells, colors, sounds of the Orthodox Church…

But in Chekhov there is no struggle at all, as if disillusionment in one’s work to which one has been ready to sacrifice one’s life, is something taken for granted. Forget the swords – even the sea does not seem to shine in Chekhov, and his characters never seem to bathe in it, no matter that this is an incomparable pleasure! It is for this, in fact, people go to the sea – not just so they can hang around the embankment and sit around in eateries. Good appetite, in Chekhov, primarily serves as a sign of moral degradation: if a hero can eat a portion of a farmer’s meat in a frying pan, then he is a lost man.

In Chekhov’s world, it is as if people do not experience the physical joys of movement, delicious food, sex…

In short, the spaces of the real world, where sparkling rivers of joy and excitement run from the peaks of strength and pride, are wiped out by deserts on Chekhov’s map. Looking at this map, I was, at times, ready to brand Chekhov’s world as an ingenious slander of God’s world. After all, he himself lived a very ascetic life and could see and admire heroes – his response to Przhevalsky’s death is super-romantic: “It is clear why Przhevalsky spent the best years of his life in Central Asia; the sense of the dangers and privations to which he exposed himself, the horror of his death far from home as well as his death wish – to continue his work after death and to enliven the desert with his grave -… Reading his biography, no one will ask: why? Why? What is the point? But everyone will say: he is right.”

This is pure Nietzsche: nothing more beautiful than to die for a great and useless cause.

* * *

Тhe reader might see this as an offence: while his favorite writer takes his heroes as models, the reader gets only sulky people who scowl in the twilight. But no, it is the reader himself that chose the scowl and the twilight.

Not all readers would be offended, of course, only those who turned Chekhov into a cult writer, and only something simple and useful can become a cult object. Therefore, neither the subtle lyricist, nor the insightful ironist, nor the ruthless depicter of stupidity and atrocity (and Chekhov, by some miracle, combined all these in himself) can become cult writers. It seems to me that the origins of Chekhov’s cult are most easily discerned in his export version, which is the one most liberated from the power of Russian reality and the luxuries of the Russian language; it is no accident that Chekhov the playwright is most popular in the West: his plays seem to be more widely read there than Shakespeare’s. What is the secret of their fascination? A singer of hopelessness, a killer of human hopes, of everything people live for and take pride in – if Chekhov really corresponded to these stigmas of Shestov, no one would love him, read him, or stage him, except for isolated misanthropes: people seek existential protection as unconsciously as sunflowers seek sunlight. If they have loved and even adored someone for more than a hundred years, it means he comforts them with something – what is it?

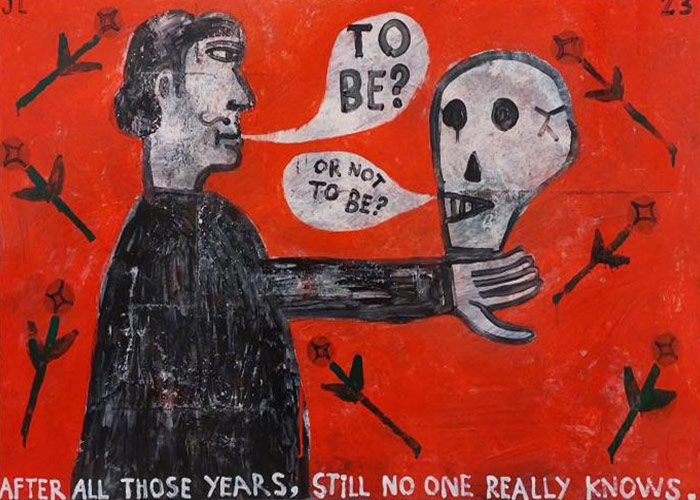

Tolstoy the Thunderer, who sincerely loved Chekhov (ah, what a nice man, just like a young lady!) once hugged him goodbye and said: nevertheless, I don’t like your plays – Shakespeare writes badly, and you, even worse. Lev Nikolaevich accused Shakespeare of a tendency to exaggerate, to create exceptional situations, and to overdo philosophical maxims that destroy the plausibility of characters and situations. But the most prominent literary authorities of the same fin de siècle accused Chekhov of exactly the opposite: he has no exceptional events, no great characters, no lavish turns, and no large-scale philosophy.

At that time, it was unthinkable to be a great writer without a great idea. Dostoyevsky dreamed of no less than uniting the state with the church; he offered the Russian man the great historical mission of universal responsiveness: to understand and love the truth of all people deeper than they understand and love themselves. Tolstoy demanded the rejection of property and state violence, starting with the army and the police. In the theater, the Symbolist drama sparkled – Ibsen, Maeterlinck – taking a swing at world issues in grandiose metaphors. Quasi-realist literature tried to keep up with it. Maxim Gorky alluded to the Nietzschean superman with his rebellious bums, and through his self-aware workers he openly called for revolution. Leonid Andreev quite overtly tried to cross realism with symbolism, anticipating the future dramaturgy of the existentialists (Sartre, Camus, Anouilh) and the prose of Saramago, inventing a new interpretation of classical images (“Judas Iscariot”).

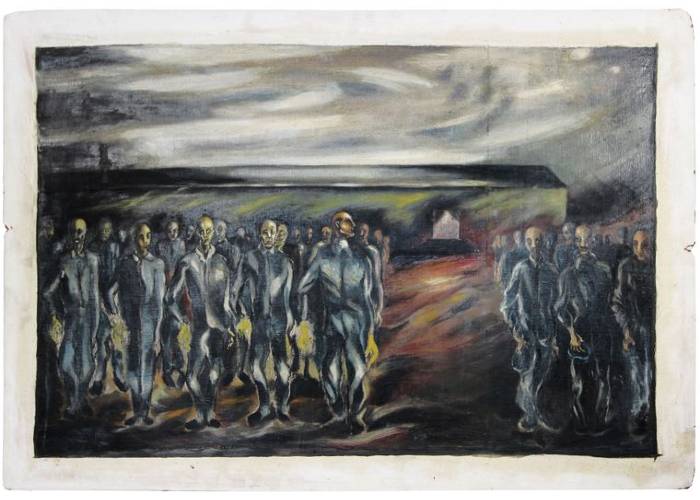

Everything bubbled and sparkled, promising unheard-of changes and unprecedented revolts. But Chekhov promises exactly nothing, referring to the rather gloomy (though not terribly miserable!) daily lives of not very happy (though not terribly miserable!) people, who, in order to feel lonesome, rise above their environment to a certain extent, though not enough to become heroes and leaders.

This is what most decent, intelligent people feel today. Today it is the norm. But then!..

Too normal – that was the common verdict of the “decadents” who wanted to build a life according to the laws of art. Not ideal enough, it did not call for a just social order, the “progressive public” believed. Not only we, with our nightmares, but the entire Western world had to endure the horrors of wars and the subsequent disappointment in all the pompous chimeras and witness the unheard-of changes and unprecedented rebellions – at least in our neighboring countries (however, everyone has had their fill of them) in order to appreciate Chekhov’s main insight: normal, not too cheerful everyday life is the most we can count on.

Chekhov portrayed, with sad compassion and stunning authenticity, the everyday life of a nice but not overly determined man – and this man pays him back in love and gratitude, in the entire world. Chekhov, by eliminating the Przewalski and Zhelyabovs from his universe, by eliminating the mighty and the determined, has thereby removed from view everything that could serve as a reproach to the weak, reminding them that man is a strong and high creature. It is more pleasant for the weak to think that it is not he personally, but man, in general, is a weak and lonely creature, whom God has allowed to bear at least his own existence, and this aestheticization of powerlessness, combined with the discrediting of power, seems to be the most suitable outlook for the modern cultural man.

Chekhov provides this ordinary man with an honorable surrender to the formidable challenges of life, and will therefore remain the favorite of intellectuals of all countries and continents until the average intellectual is transformed either into a real hero, who no longer needs a beautiful justification for his weakness or into Zoshchenko’s hero, who sees nothing humiliating in his position.