What was it that had been attracting certain Western intellectuals so strongly to Soviet Russia, even during the darkest periods of her sinister history? For a long time, I tempted just to write these people off as ignorant lefties, “useful idiots” (Lenin), before I arrived at the most obvious of possible explanations: it was the will to power. For holding the wrong views in Stalin’s Russia you could be exiled to Siberia or executed, but the poet’s status as a superior being who conversed with tsars (and accordingly possessed real political power) was never in question. Soviet power as an ideological phenomenon was unthinkable without men of letters to interpret it to the masses. Western intellectuals felt an almost childish jealousy, consciously or unconsciously, of Russian literature’s political clout. This jealousy was often confused with admiration of the country’s profound spiritual complexity.

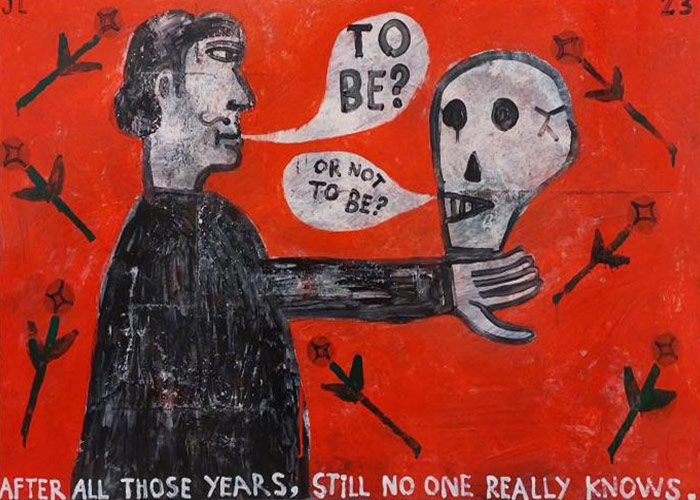

The childishness and, at the same time, cynicism of this attraction to state power, the sheer barbarism of this hankering after political potency, do not, however, mean that genuine, highbrow literature should shun authority. That is simply not the case. Literature does not reflect life, and life does not follow the dictates of literature: literature is a part of life, it is an extra life, in which the author rules as an autocrat. To the novelist, the thoughts of his characters, indeed the characters themselves, have just as much reality as trees, money, or the government. Unlike the latter, however, the words of the novelist are subject to his will: they exist, they have a life apart from the author only when they are heard back, or read, or denounced; the more people hear them, the more alive they become. The author fights to gain a public, to sway it, not for reasons of self-interest but for the greater good of his words. The more a poet is loved, the better his song.

But the years of total politicisation of Russian literature and the intimate proximity of Russian literary circles to the governmental ones has created an opposite – apolitical — trend amongst those who resented the establishment so much that they cultivated an ideal image of the writer as either as a dandy who has replaced the sword with a pen or as a kind of hermit who creates visions of beauty in the isolation of his cell. This image of the author as a monk playing only a spiritual part in human affairs does not, of course, correspond to any sort of reality. The attractiveness of that illusion to Russians is perfectly understandable. It results from a longing for civilised order amidst in the randomness of authoritarianism and nationalisation of the private word in Russia.

We should remember, though, that the separation of the private world of religion and state is not absolute and varies considerably between countries, from Israel to England. Literature, having lost its former status as sacramental religious texts, has not forfeited its role in forming society’s attitudes. Nobody in political life, having an occupation dependent on rhetoric, can get by without literature, because speech is founded on quotation. The social animal needs literary sources like a fish needs water. A sterile separation of literature from its social context implies a rigorous division of human beings into those who have and those who have not the power of speech.

To contain this power within the bounds of respectable civilised discourse and non-involvement is no better than censorship. To dispatch poets to the back shelf of a deserted little bookshop of an English village is a fate little better than Siberian exile. A major poet can be both a politician and a hermit, but major poetry is unthinkable without a major readership. A poet who renounces the social power of the word is considerably worse than King Lear when he decided to put the loyalty of his subjects to the test by abdicating, because a king without his crown is still a king by lineage, but a poet who condemns his words to eternal solitary confinement is no poet, but a tyrant.

* * *

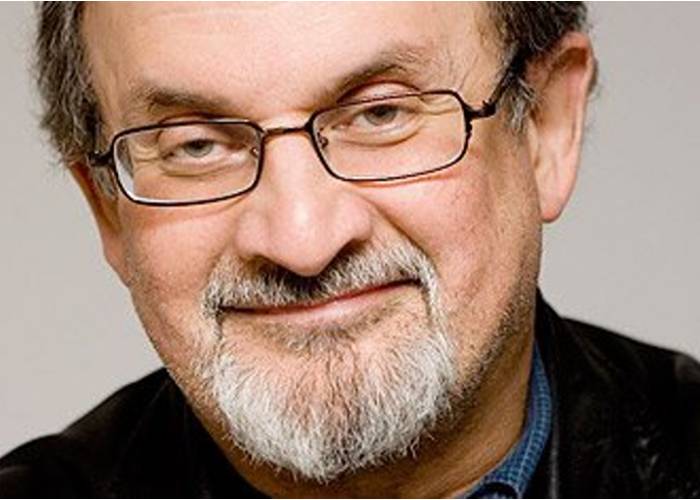

These deliberations over the question of political involvement of literature were provoked in my mind by my encounter with Salman Rushdie at an international literary conference* in Lisbon twenty years ago, at the very beginning of the Perestroika era. Knowing all that I do now, I can see why Salman Rushdie was so incensed by my essay “The Bilingual Minority”. The essay had been commissioned by the organisers of the conference, Anne Getty and Lord Weidenfeld. Translated into a number of tongues, it was intended to provide a starting point for the debating of contemporary aspects of Russian literature. I was writing about literature as a kind of verbal hybrid, born out of confrontation between the private conversation and public discourse (or soapbox oratory, or propaganda). I suggested that “a writer is by nature the bilingual minority in a monolingual crowd”. This bilingualism can be provoked both by ideological duplicity (as in the Soviet conflict between the state authorities and the intelligentsia), by the dichotomy of religious scruples in an age of atheism, or by the schizophrenia engendered by emigration. This does not mean that the writer as an individual, as a citizen, cannot profess an integrated and consistent ideology, or even be a party supporter, but his party allegiance ends when he takes up the pen as a novelist. Since these two areas of human activity (politics and writing) are overlapping, it is better for the writer to remain apolitical – which is a no less political stance. This was the area of controversy which brought about my run-in with Salman Rushdie.

In his 1940 essay, “Inside the Whale”, George Orwell, analysing the pornographic prose of Henry Miller in the 1930s about the seedy Paris of expatriate Americans, said that Miller’s dismissive attitude towards the ideological dilemmas of his epoch was the only worthy political stance in the then atmosphere of manipulation of such moral categories as social responsibility, conscience and political commitment. (This was the era of the Spanish Civil War.) It was in this connection that I quoted a pamphlet by Salman Rushdie in which he subjected Orwell to murderous criticism for his supposed quietism, accusing him of bourgeois escapism, and calling on all thinking members of the intelligentsia (or so I surmised at the time) to fashion their pens into swords.

On the very day of the panel discussion, of which my essay was supposed to be a key element, I spotted Salman Rushdie in the company of Martin Amis and Ian McEwan. The Russian participants of the debate on the stage were ingeniously divided by the organisers into three categories. Russian Soviet literature was represented by a critic Lev Anninsky and prose writers Tatyana Tolstaya and Anatoly Kim; Soviet non-Russian literature was present in the shape of Grant Matevosyan, an Armenian novelist; while holding the fort for Russian non-Soviet literature were Joseph Brodsky, Sergey Dovlatov (whose short stories appeared in the New Yorker), and yours truly.

We were all, though, coyly pretending to each other that the Soviet frontier did not exist. We were all supposedly former Soviet but now anti-Soviet writers scattered across the globe from Moscow to New York, people of the words not of deeds, and with no intention of engaging in demeaning political squabbles. However, we also all felt, like a Jew or a negro in a golf club, that at some point we would be reminded of our origins. I felt that anything negative said about Russian literature was going to be taken personally by my Soviet neighbours at the table, even though we all seemed willing to subscribe to a view of the writer as apolitical hero. Only Grant Matevosyan seemed in his corner to have no intention of concealing his socio-political commitment:

“Bastards! Bastards! Bastards!”

He repeated this at regular intervals and entirely audibly, although without making it clear who he was referring to. Only towards the end of our excursion to Portugal did I pluck up the courage to ask him whom he had in mind. It transpired that, as he looked out at the palaces and sunningly beautiful scenery of Portugal, he couldn’t forgive what the bastards – the Soviet leadership – had done to his own native land of Armenia.

The person most nervous in the presence of his compatriots was Sergey Dovlatov:

“I have only been this nervous one time in my whole life,” he said. He told me the story of how he and his wife, after some drunken party, had been staggering through Manhattan late at night and got lost in downtown. It was a muggy New York summer night. Homeless people were sprawled in the streets, drug addicts were blundering about. It was a nightmare. Suddenly a huge – taller than Dovlatov a giant — negro appeared out of a side street and began heading straight towards them. The black man was almost naked in his narrow vest and boxer shorts, with biceps like dumbbells. Chains dangled round his neck, bracelets from his wrists, and his hair was braided in dreadlocks. Dovlatov prepared to take his leave of life. His wife had to tell him what happened next. Petrified for a moment, Sergey gave himself a shake and rushed towards the black man, enfolded him in his arms and kissed him full on the lips. “Have you ever seen a white negro?” his wife asked him later. Under the impact of that kiss the black man blenched with horror. Startled, he stared for a moment at the almost two-metre tall Dovlatov, before taking to his heels with shrieks of dismay, his chains and bracelets rattling.

I waited with interest to see how he would short-circuit the tension in the air on this occasion. Unlike his old friend, Brodsky, Dovlatov was a maverick and felt equally ill at ease among the literary elites of all kinds. He was drinking more by the day. During one of the breaks between sessions, Sergey clinked glasses with me and remarked, “On the subject of your bilingual minority, Zinovy: You can make yourself understood admirably in English, but have you ever stopped to think what kind of Englishmen you socialise with in London? What I mean is, what kind of foreign friends do you have? If you look closely, you will see that they are all abnormal, not necessarily mentally, but invariably they have a defect of some description. Of course they have. No normal, healthy human being has any interest in hanging around us. Why would he?”

Circling round us émigré authors was Anatoly Kim. He would sometimes touch us and murmur, “I thought Brodsky and the rest of you writers in the West were characters someone had dreamed up in Moscow as a joke.”

The situation was, however, only too real as we sat at the same conference table on that Russian panel. Lev Anninsky was the spokesman for the Soviet delegation. To tell the truth, I wasn’t really expecting much of a frank response from him to my essay; it was enough that they had been allowed out to the West. This was the first officially permitted meeting of the Soviet elite with those in emigration. In response to my ideological bilingualism, Anninsky conjured up ingenious parallels between Nazism and Stalinism (the Western Hitler was not better than the Eastern Stalin). I was sitting to the left of Dovlatov and Brodsky at the far end of the table, and observed with horror that Salman Rushdie in the front row ominously was dexterously underlining something on a conference handout that included a printed copy of my essay. When Anninsky’s sonorous tones (simultaneous translated into four languages) and the ensuing applause had died away, there was an awkward silence. At that point Rushdie rose to his feet.

He asked why Lev Anninsky was not discussing the essay “The Bilingual Minority” in which, in his opinion, Zinovy Zinik had levelled false accusations against him, Salman Rushdie. He had never called for party political commitment in literature, even less had he proposed fashioning the pen into a sword. He claimed he had said only that the writer by his very nature inevitably finds himself in conflict with society, and has no option but to become a political figure.

I had not heard by then of Satanic Verses in May 1989 for the simple reason that the book had been published a few months later. But his insightful disquisition on the topic of literature and politics somewhat deflated my essay. Its message had indeed been no more than a rather straightforward advocacy of “Down with ideological literature, Soviet or anti-Soviet propaganda” and referred solely to the situation in those years in Russia. In my heart of hearts I was fully aware that the thorny question of the proper relationship between the poet and society had existed long before the coming of Soviet power, as had the topic of prisons, psychiatric hospitals and exile. I wriggled out of the situation by replying to Rushdie that a writer should avoid acting as an intermediary between God and his readers and remember that in literature ideas belong to characters, not authors, and can change from one novel to the next. The writer, unlike the priest or the politician, shares the ideas and views of each of his heroes with equal enthusiasm, which is why the writer’s desk is neither a preacher’s pulpit nor a politician’s platform. Tatyana Tolstaya gave me an approving glance.

At this point there came from the auditorium the still voice of a seer:

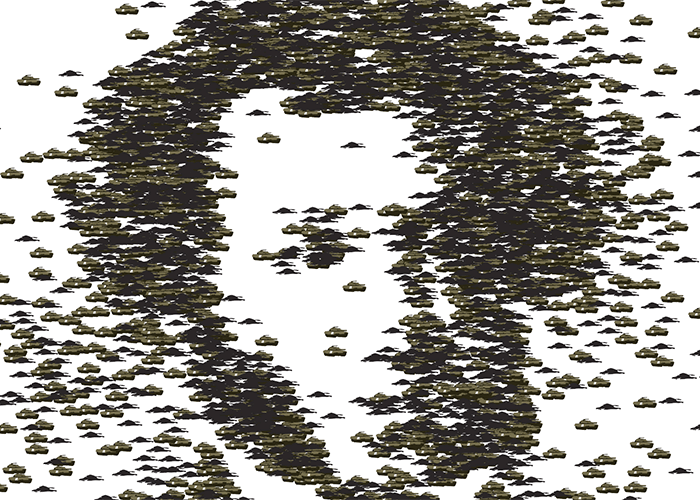

“Why is nobody in the Russian delegation talking about the presence of Soviet tanks in Central Europe?” The voice belonged to a writer called Conrad, and should have been replied to by a writer called Nabokov. Since, however, Conrad was not Joseph but George, not a Pole but a Hungarian, and since moreover this was a different age, he was replied to by a Tolstaya. Her brief (but not improperly brief) response suggested that Soviet power must be regarded as rain: outside the window it’s raining, but inside you are dry and clean and free. The Hungarian seer replied in the slow, still tones favoured by Central Europeans, “Let us out of your prison, and we will formulate our understanding of freedom for ourselves.” Joseph Brodsky rose and said that we all inside the Soviet empire live under Soviet power and there is no need to pretend that Central Europeans are any different from the rest; they are prisoners in the next cell to the Russian one, and there is nothing central about it. Czeslaw Milosz said (in the still tones of a seer) that he detected a note of irascibility in Joseph’s voice, the intonation of a latent tyrant. Tatyana Tolstaya supported Brodsky, adding that if it were not for Soviet power then so-called “Central” Europe would have continued to stew in cultural provincialism: Soviet tanks had given them a worthwhile topic for writing exciting epic novels about. That stirred up a hornet’s nest. Derek Walcott, an American from the Caribbean, detected echoes of colonialism in her words. Even I, given on the whole to excessive caution, rose to ask:

“What are you demanding of Tatyana Tolstaya? Do you expect her to hijack a tank during the Red Square parade and drive off to liberate you from the Soviet yoke?”

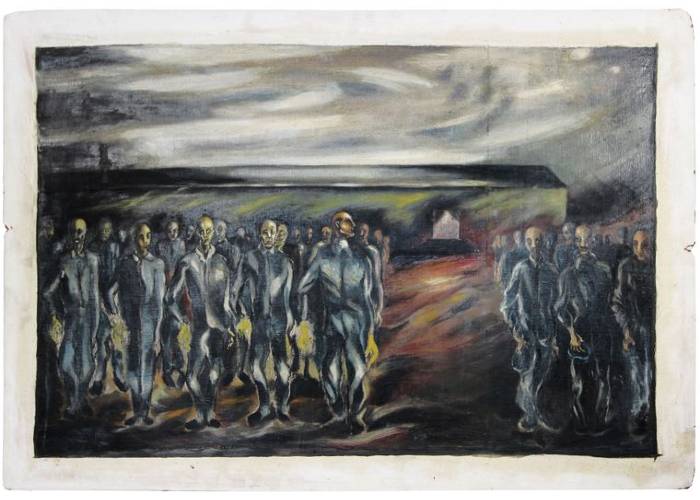

“No,” a mild-mannered Yugoslav called Danilo Kish responded, “But why do Russians write so much about the Gulag when there is not a single Russian novel about the Soviet occupation of Central Europe?”

It was a good question. At this moment I felt a stirring of the air to my left. It was the great bulk of Sergey Dovlatov rising from his seat. To rise was not an easy matter for him. He was as brimful of alcohol as a tumbler of vodka complete with meniscus. He was over-cautious not to spill a drop, but was finally on his feet and hadn’t staggered once.

“Spit at me,” he said in his clear, husky, enchanting, radio voice. “I am Russian literature, and I personally feel my disgrace, my guilt before you, our Slavic brothers. Spit at me!”

Nobody spat at him, as he started slowly sinking back into his chair. It occurred to me that Dovlatov had again been confronted by the ghost of his white negro. His contribution had been an ideological kiss of exorcism. The seers of Central Europe continued to speak in their slow, well-modulated, quiet way, but by now nobody was listening to them. Leaning over the table, Lev Anninsky, startled and nervous, told me in a loud whisper that there was so much he would have liked to say about my essay, and had even prepared his remarks, but he had to be careful in the given circumstances: “I do hope you understand. I’m sure you do.” He suddenly asked me, “Do you know why loggers attach a log to a raft of tree trunks?” I didn’t. He looked at me with knowledgeable irony and gave me the answer: “If the raft gets stranded on a sandbank, they throw the log out into the river, the current drags it downstream and the raft is lifted off the sandbank.” He paused dramatically. “Do you see? If Russia is the raft, then the émigrés are like the log which pulls us off the sandbank and helps us to overcome stagnation and crisis.”

“My dear Lev, are you really likening Zinovy Zinik to a log?” Tatyana Tolstaya enquired loudly. Anninsky retreated in confusion.

Down in the auditorium Salman Rushdie locked eyes with me and smiled ironically. He had emerged the victor in our dispute: in the current circumstances my apolitical stance looked absurd. Four months after our Lisbon encounter, his Satanic Verses were published, and four months after that it became known that the mullahs were promising any right-thinking Muslim a million pounds up-front and a place in paradise in return for the head of Salman Rushdie.

* * *

Ten years after the conference, at the preview of an exhibition by a Russian émigré artist Ilya Kabakov in the Round House, London, I saw Rushdie again. The appearance of the famous writer, accompanied by his bodyguards, at some private function is the stuff the gossip is fed on. One of such tall stories that I heard at that time was telling us of a smart London dinner party, during which a naive admirer of Rushdie is said to have crassly asked him to what extent he felt responsible for the deaths of those associated with the translation and publication of his Satanic Verses in various foreign languages. It is was an awkward question. How, for instance, would Nietzsche have felt if he had known how his concept of the Superman would be exploited by Hitler? How did Solzhenitsyn feel when he learnt that the typist, from whom the KGB confiscated the copies of his Gulag Archipelago, had hanged herself? For the overly curious young man at that party, this was an abstract philosophical question. For Rushdie, however, the very posing of the question seemed to find him guilty: his literary challenge to the Muslim world had brought about the death of innocent people. Before those present at the dinner party had gathered what the difficulty was, Rushdie, pale with fury, stalked towards the door. The hosts of the soirée, aghast, tried to persuade him to stay, apologising for the tactlessness of their young guest, but Rushdie thundered that he would not remain another minute under the roof of this house. In the hallway, however, his bodyguards informed him that under no circumstances could he leave: his car had been arranged for midnight, and it was strictly against their orders to alter the time or route of his transportation. He had to spend the remainder of the evening in the company of his bodyguards in a dressing-room, since to return to the dinner table would have been too humiliating. What Rushdie talked about all evening to those representatives of Her Majesty’s Secret Service, while fragments of urbane chit-chat floated up to him through the half-open doors of the dining-room, we can only imagine. It is a situation worthy of the pen of Tom Stoppard or, for that matter, suited to a short story by Salman Rushdie. Perhaps, indeed, he made the whole story up himself.

Throughout the two decades of the fatwa, Rushdie never stopped writing. “Even as the heart is mourning its loss, the soul is rejoicing at its find.” I quote this Sufi aphorism because Rushdie spoke in some detail about the traditions of Sufism in his family. The pathos of Sufism is its mystical duality, the ambiguousness of the hidden manifestations of human nature. There is a duality in the nature of Islam itself, caught in a dilemma between the two older world religions of Judaism and Christianity. Rushdie’s Satanic Verses are a systematic dramatisation of that duality, present also in the world his émigré characters inhabit, both in respect of religion and of education, in their Indian Englishness.

I am mentioning all theses well-known details now in order to demonstrate that Rushdie was much more, than I thought, aware of an intricate knot of political intrigues with which the group of Russian émigré writers and their Soviet counterparts at Lisbon conference were tied up together. The trouble with a strict political stance, though, is that, once adopted, it overshadows the author’s persona as a novelist who, unlike the politician, is supposed to be empathising with the whole spectre of political views.

A gigantic installation, created by Ilya Kabakov for his London show a decade later, was called “The Palace of Projects”, a parody of every conceivable shape and form of Utopian thinking. As if the representative of Utopianism on earth, the then Minister of Culture, Peter Mandelson, gave a speech at the opening: he was at that time in charge of the project for a gigantic Millennium Dome at Greenwich to commemorate two millennia of Christianity. Against the Kabakov’s installation in the background – a parody of the Soviet universe — the stage podium resembled the saluting platform on Lenin’s mausoleum. Standing alongside the Minister, Salman Rushdie ceased to look like a dissident writer, the latest victim of religious fanaticism, but was transformed in our eyes into the figurehead in a great queue of moralists, reformers and enlighteners of the ignorant masses, stretching over two centuries of the Great Utopia of Liberty, Fraternity and Equality, from the guillotine on Place de Grève to the monument to Dzerzhinsky on Lubyanka Square.

____________________________________

* The Wheatland Foundation International Conference, Lisbon, May 1988

___________________________________

This essay was first published in Times Literary Supplement, May 30, 2008