On 24 February 2022, it was over. What remained of the legends common to the two nations died on that day. Whatever vestiges of fabled folklife the two peoples still shared, vanished into the thin air of Ukraine, riddled with Russian missiles. History fell on the people hunkered down underground. Perhaps, it was Putin’s only big promise which he kept: to make history great again. It took people a while to realize what the dickens was going on, but now, a year into the war, it is clear: The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich—about two neighbors, first friends, then foes, told by an ethnic Ukrainian and arguably the greatest Russian writer—had to give way to A Tale of Two Cities.

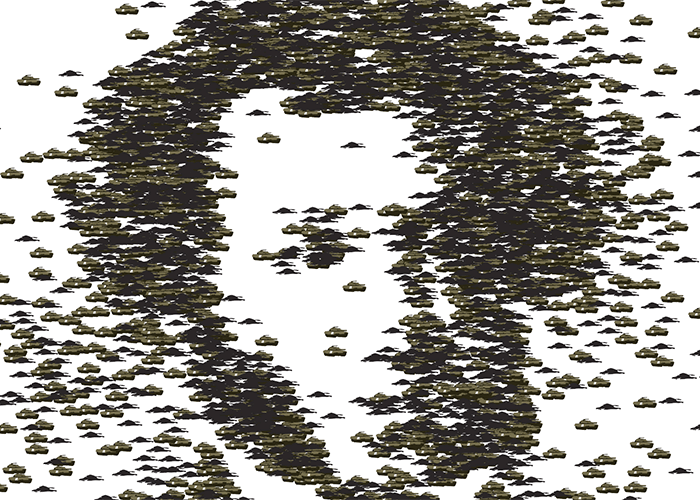

It is now the worst of times to pay homage to Russian culture, since Putin’s ruthless and senseless invasion of Ukraine rages on under the banner of the so-called Russian world, which comprises—and compromises—Russian language and culture. When on 10 October a swarm of Russian missiles attacked major Ukrainian cities, one of them hitting the former Department of Russian Philology at Taras Shevchenko National University in Kyiv/Kiev, it was all too symbolic.

The attack followed a major escalation in this war: on 21 September, Putin declared nationwide mobilization, and on 30 September the dictator yet again pledged to expand the borders of the Russian world (never mind the ensuing shrinkage of the Russian civilization) as he claimed whole regions of Ukraine as now parts of Russia. As ludicrous as it may sound, Putin bet on making Russia big again after sizing up public opinion. By 2022, the patriotic frenzy after the annexation of the Crimea had begun to wear off, and the discontent of ordinary people with the country’s economy and social policies simmered, so the gods of national self-love had to be conjured and propitiated. As per usual, the Russian führer gave a big speech aired on national television, mouthing off his jeremiads (duginiads?) about Russia defending herself against the encroachments of the treacherous West. Unsurprisingly, this did not lead to an upsurge of appreciation for all things Russian outside of Russia.

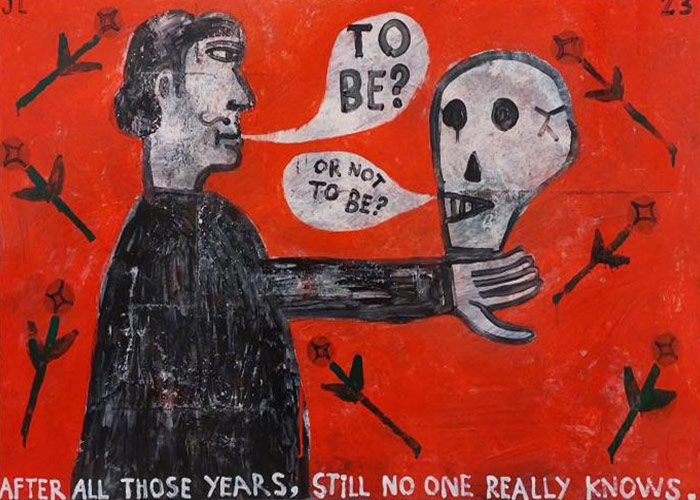

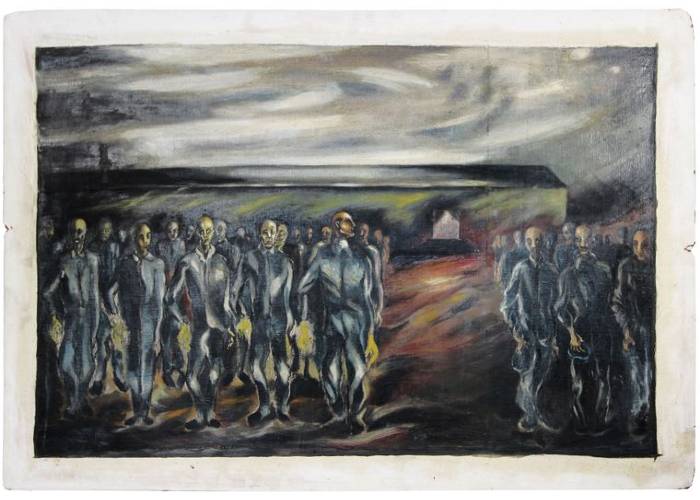

However, it is for the very same reason that the worst of times is perhaps the best of times for throwing a spotlight on Russian culture—and not just for Russian culture’s sake. Let us ask ourselves: what do we do as readers when a personage of a novel or a film is breaking bad—or worse, has sold his soul to the devil? Why, we follow the story with greater attention than before, as we follow Faust or Raskolnikov, or the lost souls described by Dante and Shalamov, Flaubert and Chekhov: we walk together with them along the path to hell so as never to tread it. It is for the same reason that we take an interest in Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Pushkin’s Boris Godunov, in Lermontov’s Pechorin and Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde, for any person can fall victim to the demons of pride and cowardice, lust for power and money, or despondency and hatred, especially hatred towards the vexing freedom of the Other.

Yet our culture is not that of crime and punishment alone; it is three-dimensional, the third dimension being redemption. The divine right to redemption is the premise of any liberal, humane, society. That is why tragedies with their “bad” endings feel cathartic, rewarding: the characters with whom we commiserate suffer so that we would not have to in our own reality. The stories of dead souls prove to be more liberating for the reader than a narrative with a politically correct protagonist who hasn’t got any prejudices, isn’t privileged, and, in a word, is not problematic.

By contrast, one of the missions of culture from the first epics to nursery rhymes has been to vent the fears, resentment, aggression, and many other execrable excesses of people, much like in our dreams: to intercept and our ugly desires and displace them from the dark recesses of the unconscious. In modern psychology, people may be judged based on their dreams, but never sentenced. The same, it would seem, should apply to genuinely free culture.

At the same time, those who fetishize Russian culture and use it as a human, or rather humane, shield in Putin’s shameful war, are not much different from those who demonize it. Both underestimate and oversimplify culture, and, at the same time, both take culture too seriously, oblivious to the fact that culture—more specifically, art—is make-believe. That it is should not beg responsibility, but it should defer it, so that we could get a chance to think: a suspension of the verdict is as crucial to art as that of disbelief. The next step is to go on with our lives, where we cannot but confront existential choices, so we act, and that is precisely when we are duly judged. That is why, however understandable, the public backlash against Russian culture after Putin’s Hitleresque invasion of Ukraine betrays those of little faith. Likewise, the silence of the idolaters of Russian culture who show no scruples about the evidence of the heinous crimes committed by the Russian army in Mariupol and Bucha betrays a lack of understanding of the texts written by Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, or Lermontov and Gogol—rife with sarcastic observations about Russia.

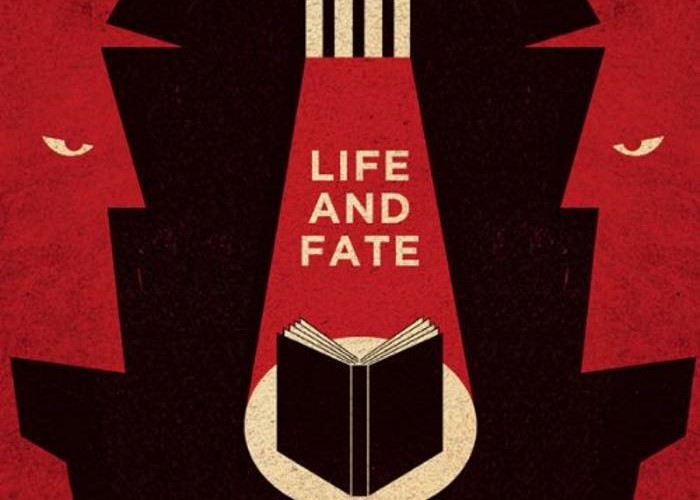

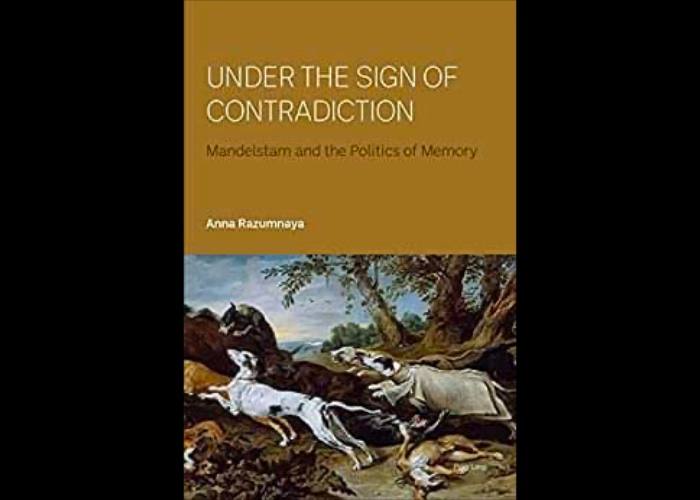

Sadly, too many people, including those opposed to Putin, swallow the bait and play into Putin’s hands when they concede classical “Russian culture” to him. I put quotation marks around “Russian culture” since by now it sounds almost like a brand for some and a label for others—and definitely not the thing it is supposed to denote: the place where people seek freedom and truth—a galaxy of meanings, neither “good” nor “bad,” its gravity impossible to deny. What we deal with here, as with most generalizations, is a strawman—a trap to make us lapse into the same fallacies as Putin.

The first fallacy is when we hypostasize, that is, personify, Russian culture as though a leviathan, mythologizing it and thereby presenting it as exceptional. The second fallacy is that of anachronism: we wrongly consider Putin as a legitimate successor of Russian nineteenth-century rulers and Putin’s Russia, an extension of the same old Russian Empire. Both assumptions are part of Putin’s false narrative; meanwhile, suffice it to read Russian literature of the nineteenth century to see how different the social structure of Russian society was. The original sins of Russian culture, whatever they are, remain, but not the sinners, much better judged by the juries of their own time. Furthermore, the fact that the whole of Russian culture is made a scapegoat for Putin’s crimes is another false narrative—that of centralization, when, time and again, those superb poets of today who write in Russian and yet are not Russians but Ukrainians, are associated with the kind of Russian culture that is headquartered in the Kremlin, so to speak. When France does something terrible, the whole of Francophonie is not held responsible for it; the same is true for the Anglophone world, and while the Russian state brought the boycott of Russian culture upon itself, it is up to us whether to perpetuate the attempts of talentless Russian rulers to hold the whole of Russian culture hostage. Consequently, the third fallacy is that by blaming the crimes of the Russian government on Russian culture, we downplay Putin and his cabal’s personal accountability.

The truth of the matter is that, more than the bulk of today’s critics of Russian culture combined, it is classical Russian authors who brought Russia to book — or rather to the books they wrote: Chaadaev, who doubted Russia as a fully-fledged nation partaking in world history; Saltykov-Shchedrin, with his scathing satires of both the government and the common people; Gogol, Goncharov, or Turgenev, who unveiled the existential abyss of the Russian soul; Dostoyevsky, with his prophetic writings about the Grand Inquisitor and the lost, confused people who turn into idolaters; and, of course, Tolstoy, whose anti-war writings, if he lived today, would get him the Nobel Peace Prize, for which he was nominated but which he did not crave, because Tolstoy was bigger than national and linguistic borders and even those of the noblest of institutions, showing us all how not to be cowed into conformism—a sin which is especially tempting in our global village with its hive mind.

And yet the history of our civilization, recorded and philosophized in our cultures, Russian culture included, shows that the crimes committed on behalf of the country turn into the original sin of all, making every citizen an accessory, if not before than after the fact. That is the tragedy of humankind, and, alas, it is Russia’s turn to teach the lesson. Before Russia, it was Germany’s, which is why it seems appropriate to conclude this essay with the words of a prominent representative of the German-speaking world, Carl Gustav Jung:

“Now that the angel of history has abandoned the Germans, the demons will seek a new victim. And that won’t be difficult. Every man who loses his shadow, every nation that falls into self-righteousness, is their prey…. We should not forget that exactly the same fatal tendency to collectivization is present in the victorious nations as in the Germans, that they can just as suddenly become a victim of the demonic powers.”