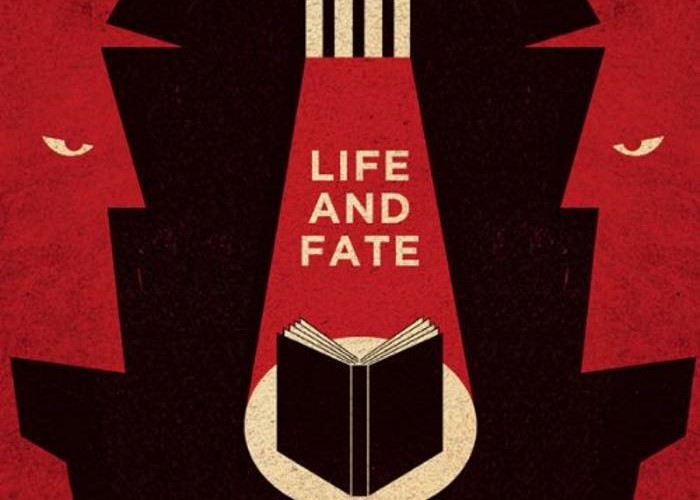

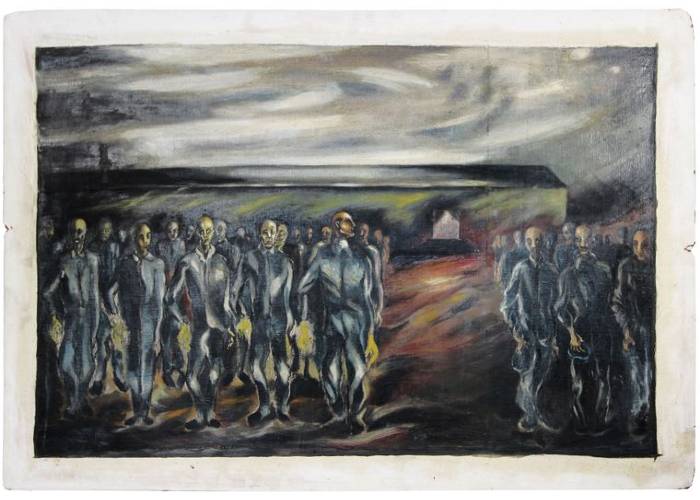

I’ve begun reading Yuri Slezkine’s mammoth work The House of Government, which is a history of the Soviet Union told through the eyes of the inhabitants of Moscow’s House of Government– -a huge residential complex created to house the government and Communist Party elite after they moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow. There are many vivid literary accounts of terror-stricken life within the Soviet Union but Slezkine’s story is populated by characters for whom the revolution was not some wild storm that blew their lives to bits, but rather a rational construct that was the necessary precursor to ultimate human flourishing.

They were the true believers. Yet even before the worst of the Stalinist terror and purges it’s astonishing how quickly these people are reduced to hollow shells and nervous wrecks– unsalvageable human ruins.

I’ve been discussing this with a couple of acquaintances and the consensus seems to be that this was a result of remorse of conscience. Maybe. I’m becoming more convinced it was simply stress– -the unanticipated stress that results from having your props jerked out from under you, props you didn’t know existed until they were gone. Even a strong, centered person might crack under the circumstances that were unfolding. As shitty as the old world may have been, it was normal, predictable, accounted for.

The new world was—what? Still an idea, and even worse, an idea without legs, “legs” being the huge interconnected web of laws, customs, institutions, and offices that allow a society to function day to day. The old legs were in the process of being chopped off on the theory that they supported the old regime and had to go. But the legs that were to replace them were entirely theoretical and made no appearance of themselves. So the head of the machine had no choice but to become the legs as well, which it tried to do extemporaneously with administrative diktats and guns. Unfortunately, this didn’t close the distance to the new world, it just replaced the old world with a world of complete uncertainty and hazard, where only raw power prevailed. Who wouldn’t go to pieces in such a place, especially those in a position to see it unfold in all its hellish clarity?

And the typical revolutionary-become-bureaucrat was weak. He was not a successful, experienced man of the world– -he existed at the fringes of society: poor, angry, feeling disenfranchised, unlistened to– committed to an ideal that may have well as come from Mars. But suddenly such people became the decision makers, or at least decision implementers, and stood at the center of political life. Slezkine’s portrayal indicates that very few of them were suited for such roles—children suddenly required to become directors of state, and given responsibilities far beyond anything they could have imagined let alone held.

There’s no doubt that a similar (though less dramatic) story unfolded when the Soviet Union collapsed. Steven Myers’ biography of Putin discusses how he succeeded in rebuilding portions of St. Petersburg’s infrastructure when he worked for the city’s mayor in the early 1990s. Among other things, he wrote and managed privately-issued public construction contracts that would have been illegal in most of the Western world. Why were they not illegal in Russia? Because the Soviet Union was not a capitalist society—competitive contracting, procurement law, and all the rest of the vast paraphernalia and custom that supports free commerce was not practiced and did not exist there—all such things were controlled by the state.

With the collapse of that state, once again their society had no legs. This left the door open to those who could achieve success by any means, and for whom crime was defined weakly by rumor rather than strongly by law. Frankly, it is probably impossible to understand the full effect of this from the outside, where all the fiendish intricacies supporting our way of of life are completely taken for granted, and the consequences of losing such support could not be calculated or even imagined. But Slezkine gives us a good glimpse of it, with all of its stress, desperation, and abandonment to power.