A few days ago I posted a link to the podcast that featured a conversation with writer Yossi Klein Halevi. Halevi brought up a few points that I think are very important to make and understand if we’re to identify the sources of the latest surge of antisemitism, which, it seems, is now being embraced and articulated by some of the West’s young and educated.

Like many Soviet kids of my generation, I grew up in the shadow of WWII. My grandfather perished in the siege of Leningrad, my grandmother died two years after the war – in part, due to malnutrition and other wartime deprivations. We were not directly affected by the Holocaust. But on my father’s side the family came from a shtetl in Belarus, which had a prewar Jewish population of about 4,000. As far as I know not one of those Jews was alive by 1945, the town itself vanished off the map. I’m writing about this not to showcase yet another tale of Jewish suffering, but to make it clear that for people like me, the existential danger to Jewish lives has always primarily emanated from the extreme right, from… well, from fascists. Yes, there was plenty of antisemitism in the Soviet Union, but I was lucky enough to grow up in the late-Soviet era when antisemitism was definitely felt but hardly deadly. I guess it could be deadly in an indirect way. For example, few Jewish students were admitted to the universities and colleges granting deferments from military service. At the height of the war in Afghanistan, that could become a problem with possibly fatal consequences. But I never felt threatened directly (a few fights with neighborhood hoodlums didn’t count).

When did I first feel personally threatened? Possibly during that white supremacist march in Charlottesville back in 2017. Watching the fascist goons parading down the street, chanting “Jews will not replace us”… that was unpleasant. Later on, seeing Trump’s serenely indifferent smug mug and hearing his “fine people on both sides” hardly alleviated those apprehensions. And then the Tree of Life Synagogue shooting followed and it became quite clear that something very poisonous was diffused in the air, that Trump’s very presence on the scene, his professed love for Israel and his Jewish grandkids notwithstanding, stirred up something very dark deep inside the American psyche. That was very worrying, but it was also obvious to me that the cultural, personal, and academic spaces that I inhabited were free of this poison. Friends, colleagues, students could be relied on to be appalled by rightwing antisemitism. In the aftermath of the Pittsburg shooting quite a few people on Facebook put up Jewish stars as their avatars. That was reassuring. But there were no stars of David following the antisemitic bloodbaths in Jersey City and Muncie, NY. No one seemed to notice the spree of almost weekly assaults on Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn that had escalated into a real community-wide crisis by 2020. The problem was quite clear but not appropriate for an honest conversation in polite company, because that violence was perpetrated not by some rightwing bozos, but by representatives of “minority populations.” Violence against Jews was readily condemned when it came from white supremacists and trumpist morons. But when the perpetrators could be construed as “oppressed” and “marginalized” then too many of my fellow liberals preferred to keep mum. Some facts were too inconvenient. To be honest, I found that strange silence in the face of violence to be disgustingly racist. John McWhorter has spoken and written eloquently about this sort of racist condescension that ultimately makes American racism even more entrenched. There is nothing enlightened or progressive in assigning different moral and ethical value to human behavior based on group affiliation. And there is nothing progressive in turning real human beings into the place holders and cutouts in the imagined pyramids of oppression.

And that brings us back to the issue of “Jewish power.” Or maybe it doesn’t… But whatever. In 1986, not eligible for a deferment because of the issue mentioned above, I was drafted into the army. Jewish families dreaded sending their sons into the military service as it was generally assumed that Jews would be mistreated. Many returned from the service traumatized. But my experience turned out to be ok – maybe on account of my personality (quite sunny back in the day) or just plain dumb luck. In fact, I still have some fond memories of that time, but that’s likely the function of nostalgia.

On my very first day at the base, we young recruits were lined up in front of the barracks. The scene reminded one of those harrowing drawings of slave auctions in the American South: the officers inspected the new arrivals to pick out the ones they wanted for their battalions. The officers were especially interested in specialized skills, they wanted to know who could drive, who could cook, who could paint, who could repair engines, etc. I could do none of the above. Senior Lieutenant Andreev, a chubby but very handsome man, circled me with obvious curiosity. He brought his thumb and an index finger close to my nose, jokingly measuring its size and then issuing an appreciative whistle. “Impressive,” he said, “so you’re one of THEM, huh?” I didn’t have to ask him what he actually meant. Resigned to my fate I just nodded: yes, one of them. But unexpectedly, Andreev looked pleased, his rakish smile revealing two rows of glamorously white and evenly aligned teeth. I had never seen such beautiful teeth in the Soviet Union. It was those teeth more than anything else that made me realize the inevitability of my coming submission to his will. Andreev announced that I’ll be joining the battalion under his command because he “needed someone like you.” I didn’t dare to ask why I was needed, but Andreev explained anyway: “You people are really something else, there is nothing impossible for you. Stay close to me, I’ll make sure you live, and you’ll help me when I need you.” This declaration of partnership sounded like a threat, but I was in no position to either reject or question it.

Actually, our relationship would eventually evolve into a weird sort of friendship, whereas Andreev held all the power over me, but often sought my advice or expertise on a dizzying array of issues. For example, once he asked me to translate into Russian the lyrics of Stevie Wonder’s “I Just Call to Say I Love You.” The song was popular with junior officers, and Andreev in particular was obsessed with it. One day he placed me by a beat-up cassette player Vesna 202 in the Lenin Room and let me listen to the song and write down the translated lyrics. The assignment was a distraction from a pretty depressing routine in the barracks and out on the firing range and I welcomed it. My English was almost nonexistent, but Andreev didn’t know that. So I just made up some random words and made them rhyme, to Andreev’s exuberant delight. For weeks afterwards Andreev and his buddies sauntered around the base belting out my lyrics. I truly felt like an accomplished poet.

I have to say his confidence in my abilities was not confined to foreign languages and poetry. He also regularly consulted me on matters of his cock, of which he was very proud. Once he grilled me for what seemed like hours about various ways to improve his sexual performance. Deep inside his excitable mind there persisted some kind of association between Jews and medicine. At the time, he had just made the acquaintance of a young textile factory intern from Ukraine and was desperate to impress her in bed, or rather on a pile of discarded trench coats, assembled for such romantic purposes in the storeroom in the back of the canteen. I knew that in order to maintain the fiction of my omnipotence I had to come up with a plausible technique. We discussed a few options at length and settled on a trick that, I thought, would be less potentially harmful to his health. I’ll skip the titillating details, but it involved tightening up Andreev’s scrotum with a shoelace. To my great relief, the shoelace trick worked. At least that’s what Andreev claimed next time he barged (he never just ‘entered’) into the barracks. This was just one of many such tests that I dreaded of failing. Even at this early age I understood well that disappointing someone who imagines you to be all-powerful can be really dangerous. Incidentally, many years later I got a phone call from Andreev on one of my return trips to St. Petersburg. It took me a while to remember who he actually was, but when I did I experienced a mild nostalgic feeling. Andreev had left the army and was now selling cars in Moscow. He needed my advice, because he wanted to expand his car selling business into the United States. He offered to form a joint venture. With some trepidation I demurred. I explained to him that I was a graduate student in a small town in the Midwest, where I was delivering pizzas for a living. He asked me about a model of the car I was driving. “Honda,” I said, “Honda Civic.” The former senior lieutenant sounded impressed: “Wow. A Japanese car. That’s cool. You people always know how to get quality products.”

I heard somewhere that Andreev had died. Of what? Who knows… He drank too much even back in the army days. Already portly as a young lieutenant he had probably grown overweight in his later, car selling days – I’m sure of that. And, of course, he smoked like a chimney (wonder what happened to those beautiful white teeth of his…). Also his obsession with his dick could render him vulnerable to bad actors. If he was willing to choke off his cock with a shoelace for a promise of a prolonged erection at the age of twenty-four, I fear to think what else he was prepared to do to himself, especially as a mature adult. There are not enough Jewish doctors around to safeguard and cure every self-destructive antisemite, even the lovable and unselfconscious ones – like Andreev.

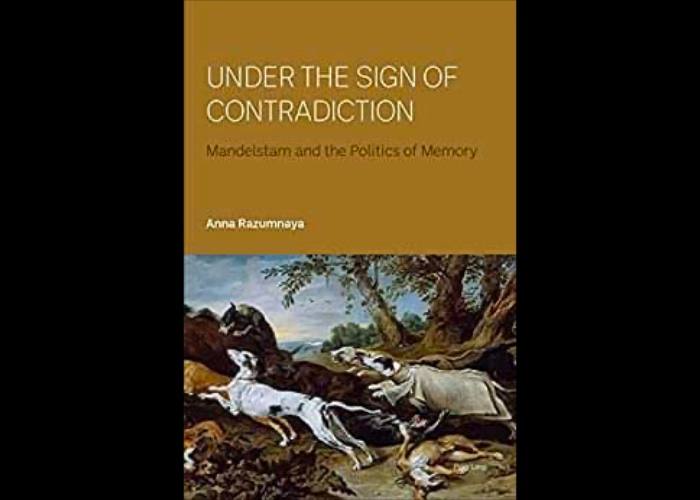

Conspiracy theories have long fascinated me. Now, after the experience of the last few years, I find them more scary than fascinating. It used to be just curiosity about a phenomenon that featured sometimes large groups of people embracing what seemed to me like obvious and easily disproven absurdities. Why would anyone follow Jim Jones into the jungle in Guyana? Why would a seemingly sane person listen to a creep like Keith Raniere for a couple of minutes and not realize that the guru is a bullshit artist (and a rather pathetic one)? Why would anyone take Trump seriously? Why would people believe in QAnon and all the extravagant and obviously moronic nonsense that it peddles? How can someone, who gets up in the morning, brews his coffee, and goes off to an office job, also believe that George Soros and Bill Gates are running a shadowy global government out of a mountainous hideout in Switzerland? How could an established Western academic apparently sincerely embrace a nightmarish vision of Israeli soldiers harvesting organs from Palestinians in the West Bank? With time, I began to find this conspiratorial outlook both disturbing and personally threatening. It seems that sooner or later pretty much any conspiracy theory leads its adherents to similar conclusions, and these conclusions bode ill for the Jews… What did Andreev see when he looked at me? Because he didn’t see what was palpably right in front of his eyes – a scared, skinny 19-year-old in an ill-fitting uniform. To my great regret and apprehension, I didn’t possess the powers he associated with “someone like me,” but was there any way for me to communicate this simple truth to “someone like him”? Would’ve it been possible for me to reject his notions of me and not antagonize him in the process? And if he persisted in his delusions (as he did) at what point could those delusions turn into fear? Or hatred? That’s what happens when we convert human beings into symbols, quite often this is a one-way journey, leading to doors of no return.

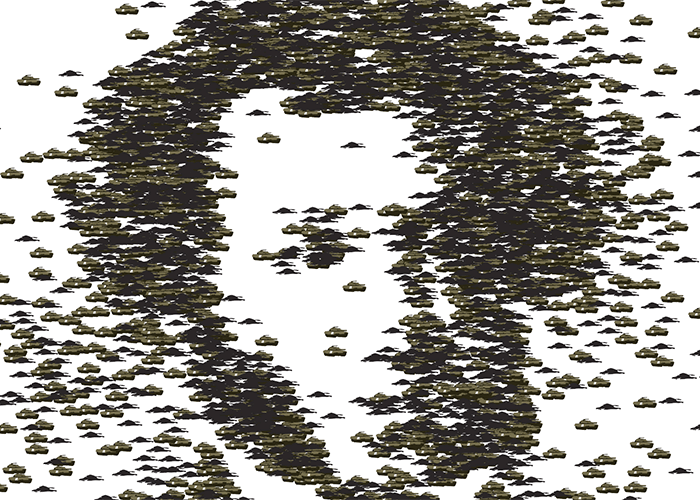

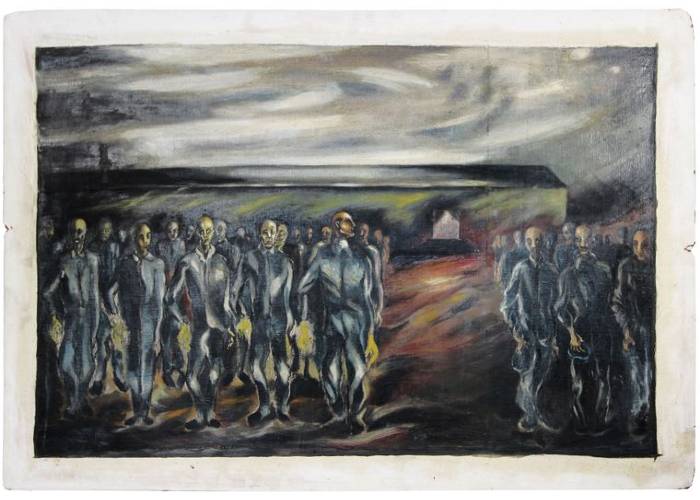

Last winter, I spent hours walking through the snowy woods of Northeastern Pennsylvania, listening to an audible edition of Ullrich Volker’s new two-volume biography of Hitler (yes, my idea of pastime). An absolutely incredible book, which I cannot recommend highly enough. I’m not an expert on German or World War II history, so I found a lot of things new and surprising. And what surprised me most was Hitler’s attitude towards the Jews. You may think, duh, who doesn’t know that Hitler hated the Jews… And you’re right. Of course, we know about Hitler’s obsessive antisemitism. But I was surprised to learn how much Hitler (and Goebbels and quite a few other Nazi goons) feared the Jews. Jews terrified them. Even when they were gassing and shooting Jewish men, women, and children in millions, they were afraid of them. Hitler had convinced himself that the war he was waging against the British, the Soviets, the Americans… was a war against the Jews. Ideologically, the Nazis had been conditioned to see past or through the corporeal. When they herded the Jews into those ghastly gas chambers, they were not dispatching the terrified and the powerless, they were destroying a symbol of power. Yes, they were acutely conscious of hierarchies of power and it was that consciousness of injustice and it was their fear that motivated them to murder the alleged oppressors. Not every single Nazi was a psychopath, probably, most of them were just regular and… gulp… well-meaning people (just read Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men). But many of them had internalized a worldview that identified the Jews as all powerful and deadly. They were saving themselves from a mighty adversary. And they were saving the world.

This is something that occurred to me as I was listening to that interview with Yossi Klein Halevi. He was asked about this bizarre fad of Western students tearing down the flyers with faces of Israeli captives. I mean, you can support the cause of free Palestine all you want, but destroying an image of a 9-month baby, whose parents were brutally murdered just a few weeks earlier and who is now kept in captivity in some underground tunnel? And the violence, with which these young and well-intentioned Westerners destroy these flyers… They really rip them to pieces – it’s a symbolic act of vandalism and ritualistic murder that needs to be understood. And here Halevi, I think, is prescient. He doesn’t attribute these acts of symbolic violence to antisemitism, at least not for everyone involved in them. Something else seems to be afoot here. It is unbearable for these youngsters to see Israelis as victims, because such imagery undermines the main premise of their worldview: evil needs to be powerful to motivate the just to destroy it. These flyers truly make these students mad, because they can potentially make them question the righteousness of their worldview. And that questioning is absolutely unacceptable. The Israelis, the Jews are powerful, they oppress, they exploit, they “colonize”… Any story or depiction of Jewish suffering that runs contrary to this conviction needs to be ignored or better yet expunged. Hey-hey, Ho-ho, Holocaust Studies got to go! Did you hear that chant? Not yet? You will hear it soon.

Wonder what my old friend Andreev would’ve made of it… Wonder if he went to his grave still believing that a skinny kid from Leningrad was actually a miracle worker in disguise. In some ways, I have lived my life in the shadow of his expectations. He was like a Jewish mother to me. He expected much from “people like me” and I didn’t want to disappoint him. But also… also… I feared him. I feared that he was afraid of me.