A JEWISH MOTHER IN THE MISE-EN-SCENE OF THE HOLOCAUST AND AT OTHER TRAIN STOPS

To my grandmother

A Jewish mother survives exclusively on food leftovers, as is customary. She cleans plates after everyone.

“Once I finish your meal for you, I’ll know your thoughts.” I was dutifully frightened by every such nudge from my Grandma (and from Mom, too, as my mother had adopted her mother-in-law’s threat!) and smeared splotches of mashed potatoes over my plate with renewed vigor. My thoughts weren’t on the level. Although this had to be evident without finishing my mashed potatoes.

But their intrusive care was no less embarrassing than their desire to invade either my digestive process or my consciousness itself.

Soviet Jewish children learned to be ashamed of their overly-loving mothers. As for the American pop culture, there the Jewish mother came to be seen as a quote from a standup joke, a container of guilt, an almost-archetypal character.

I’d like to build something like a monument to a Jewish mother the guardian and strategist. Or rather, bring pebbles for a cairn. The notion of a cairn does not come from Judaism, but stones do have a special meaning. Piles of stones mark Jewish graves. They symbolize the eternal presence of a soul somewhere nearby. Beit Olam, a grave as the eternal home, is where the soul of the deceased stays and the stones merely hold the soul without letting it leave the grave, the receptacle of the decayed body. Let them be calm, let all their stuff be with them.

My first stone for the first soul commemorates a small woman, withered by osteoporosis and G-d knows what other ailments, who every Thursday, for years volunteered at the clinic where I used to work. A retired social worker, she didn’t want to stay at home, so she came in, answered calls, performed meticulous, even obsessive phone screenings with prospective patients, and gossiped with receptionists during breaks. With the arrogance of a young professional, I flew past those lowly clerks who were sitting in the open front area behind a wooly partition; that is until it came up in a conversation that she and I shared the same alma mater. I started to slow down and look closer. Soon I noticed an oversized navy-blue number, traveling across the light blue of her veins, barely fitting the shrunken wrist. Felicia did not hide the concentration camp ID, as it long became a part of her. One day at lunch, we discussed the transformation of Jewish surnames in the process of migration, and Felicia said, “You understand that I can’t be a Hyatt. You’re kidding, Hyatt!.. I’m Hymowitz, just Hymowitz. But it was better not to attract attention. McCarthy wasn’t crazy about Jews either…” And she went on to share how in the fifties she had to cover the title of Marx’s book, her School of Social Work’s reading assignment, while on the subway so she wouldn’t get in trouble.

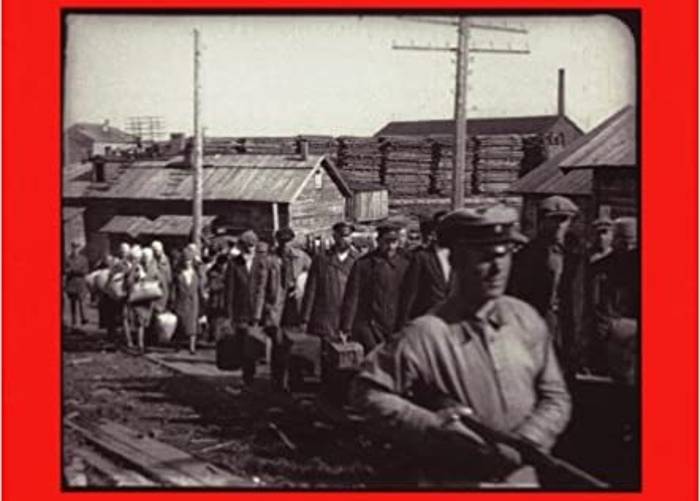

Didn’t I know the drill? I had to go through my own school of identity loss when Jewish names had to be concealed like a cattle brand. In Soviet times, the names had to match the standards of the Great Empire, had to be Slavic or Western depending on the fashion of the year. For example, my grandmother Ethel, Baruch’s daughter, was transcribed as Anna Borisovna in her Soviet passport. This name, Anna, rescued her from starvation. In 1941, after all, when the men had been drafted, my grandmother remained the only able-bodied person in a large family consisting of infants, the elderly, and less energetic female relatives. Many times I heard her story of transporting thirteen family members from Kirovohrad Oblast’ across the Dnieper to safety. They got off at the station of Kolyshley in Penza Oblast’. The grandmother saved the entire group in the challenging conditions of the countryside evacuation, where there was neither work nor housing for evacuees, thanks to the fact that she managed to get a new passport with a new nationality, “Ukrainian,” and with this passport she immediately found a job, and not just any job, but a cafeteria job. Even back then, she already could do any kind of work. No one else managed to land a job; therefore, until 1943, her earnings provided for all of them: for my teenage aunt and my toddler dad; for Grandma’s mother and mother-in-law, for her sister, nephews, aunts and for the sister-in-law with a baby …

Who came up with those names under which they could hide from death and from the cold of mortal agony?

A Jewish mother knows how to keep secrets.

But before I go back to Felicia and write about her mother, I want to identify the actors, the members of the secret society of the Holocaust silencers. The secret in common was their survival, the fact that they hadn’t perished in the Old World. Their secret became their shame, the guilt of those who escaped to the New World. I interviewed many representatives of the second generation of Holocaust survivors, those who grew up in the everlasting presence of secrecy.

The history of my people is a chronic malady, an imperceptible wound, a shameful irritation under clothes, and an annoying little pain that threatens to enlarge any stressor. It is not resolved, and there is no remission, and one has to put up with what has already happened. It elevates and disgraces at the same time, offering superficially tragic interpretations of key events for the rest of one’s life. Every rescue story is incredible, and the scars left in the next generation — the next generation’s legacy — don’t heal.

Here’s one story: “When the Nazis came to Holland, my father’s entire family hid in a shelter for the mentally ill. The father was the youngest and could not pass for the patient, so he was taken to the uninhabitable attic. After some time, all the patients were taken away. They were all shot, but no one went up to check the attic. My father told me this story just before he died. In all the previous years, he had never mentioned what happened to him during the war.”

Here’s one more: “My parents met at a relocation camp. That’s all I know about them. My sister once recorded a video where they talked about what happened to them and their families during the war, but I watched only up to the moment when my father described how the occupiers violently molested his younger sister; she jumped out the window that night. I don’t want that knowledge. I couldn’t watch any further. No one had grandparents, neither I, nor any of my friends in the neighborhood where I grew up. Very few had aunts and uncles. Yet, our parents all came from large families.”

It is the Jewish mother who becomes the root, the matrix that connects the present to the past and the future. She maintains unity.

The Jewish mother observes and infers, infuriates and figures out.

Felicia, who had gone through the schooling of psychodynamic psychotherapy, could not keep silent about what had happened to her and six million others, and wrote the book titled “Close Calls”. After the camp, Felicia could no longer carry the pregnancy to term, but in essence, she was a real representative of the constellation of Jewish mothers: her memoirs give us a proverbial JM’s advice, a step-by-step guide to survival anywhere, including in Birkenau and Auschwitz.

She describes in detail the last day spent with her mother in the vicinity of Chełm (Poland), Felicia’s hometown. At first, they found a hiding place for both of them, but then Felicia’s mother decided that together they had a lesser chance of survival. Her mother gave away her own coat and added, “I raised you like a good Jewish girl, but now I urge you to forget those rules of conduct that may prevent you from prolonging your life even for a day.” From that moment on, Felicia’s decisions, incredible for a nineteen-year-old, were based on her mother’s unconventional wisdom. She ended up in a concentration camp (not just any camp but a sinister branch of Auschwitz, Birkenau, an “official” death camp), as a result of weighing choices between a chance to survive in the camp and an imminent death in a soldier’s brothel. She survived the camp by creating her own system: to reason and calculate, to watch, neither overestimating nor underestimating the Germans, to remain humane and take into account the human nature of her guardians, never to get sick …

Her memoirs did not make the top of WWII reading lists: she wrote about the nitty-gritty of survival in too much detail, being too casual about the Holocaust. To me, the book seemed honest and open, like Felicia herself, filled with common sense and down-to-earth details that are more terrifying than a blood bath, and if no one has ever reviewed her memoir, then I must do so.

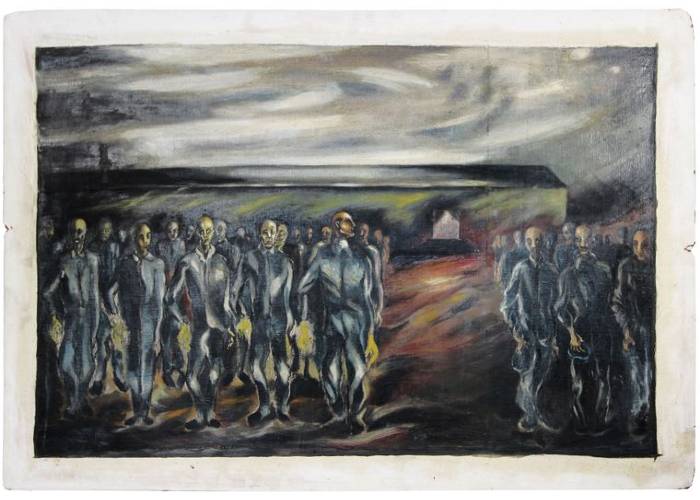

I place a mental pebble, a bookmark, in memory of her mother, whose grave could not be found, whose demise remained unknown, and will proceed to the next story that began (for me, at least) at the exhibition of Boris Lurie, the late artist, poet and memoirist, at New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Lurie’s memoir, “In Riga,” is based on diary entries that filled an old box found in his archive after his death. The central figure of the memoir is his mother. Sheina (Sofia) Borukhovna Lurie – a native of a Belarusian shtetl, who moved to Petrograd after getting married, then moved to Riga after Stalin came to power. Sheina was a practicing dentist until the very beginning of the war. Once she found herself in the Riga ghetto, the mother of sixteen-year-old Lurie decides to divide the family and tells her husband and son to report to a work camp. This is how the men avoided being shot. A timely decision saved the youngest and the eldest, Boris and his father, and they had a horrifying experience of watching, from behind the barbed wire, the shooting of the grandmother, mother, sister, and girlfriend of the memoirist. As a result of her timely decision, her men avoid execution. The extermination of women, through whom the Jewish lineage gets established, is a nightmarish metaphor for the destruction of the nation.

And what about the exhibition itself? Images of women transform from one painting to the next one. A dominatrix, a savior, a feisty bitch, a sadist, a lover, and, of course, a mother. The halo around the female figures, those painful breakthroughs through the fog, resemble Munch, but this is to be expected, as nightmares inspired both artists’ work.

Dreams, insomnia, the Holocaust – these could be the themes of a separate essay. Judging from his diary entries, Lurie slept only during the day; he learned this skill in Buchenwald, and that’s the way he functioned until the very end.

Here’s the story of yet another representative of the “second generation”, whose parents carried the Holocaust in them: “I do not know how to sleep. I can never fall soundly asleep. In my early childhood, I remember the attacks of the furniture, of a radiator from the corner. Later on, there were comic book heroes who tried to strangle me. Mom didn’t know what to do about my sleep problem because she herself never slept. I used to check at night to see if she would fall asleep. No, she didn’t sleep. She only closed her eyelids. But she was ready to jump up in a second. My mother and her older brother had been hidden by people on the farm. I don’t know if their parents paid these folks before being transported [to Majdanek], or if they knew this family before and just took pity on them. Some Poles took pity, too. During the day kids were hidden in a stable, and at night, when the occupiers came to the farm for fresh food, they were taken far into the field, and there they lay in the high grass. Mom remembered the alternating smells of manure and some herbs, and how planes crowded (sic!) in the sky above them. I don’t know anything else about that time in her life, and don’t ask me what happened next. But we never really learned to sleep – none of her children knew how to sleep. If you fall asleep soundly, you can be killed – we knew this much.” They lived in the time when the Jewish life as a whole was completely dismantled, dissolved in a fog, and individual human lives suspended.

I put an imaginary pebble on another grave that doesn’t exist: Lurie returned to the killing site, the Rumbula forest, in 1975. He took several photographs (his hands shook, and the image came out blurred), and then for the rest of his life he could not get rid of the compulsion to draw and redraw the exact plan of the execution grounds, marking the modern map of the area with an outline of the ditches (in the seventies, they erected a modest monument to the “peoples who suffered from Fascism”). I imagine placing it on top of the tombstone, as if this pebble could bring relief, forgiveness, and peace.

A Jewish mother, amidst endless valuable instructions on how to live one’s life right, orders her children to forget her and her CW (conventional wisdom) if necessary.

Felicia’s mother gives away her only coat, quite unequivocally recommending prioritizing survival over previously proclaimed moral values.

Lurie’s mother pushes the decision onto her men.

My grandmother, who was evacuated to the unfamiliar Penza Oblast’, an unfriendly territory, uses the opportunity to cross the constricting word, “A Jew”, out of her passport.

The other day, Tino Villanueva, a poet, sent me his book about Penelope. His preface explains that Homer’s Penelope evokes for him the image of his own grandmother. I wondered which of the characters from Greek mythology my grandmother resembled. Perhaps, she’s closer to Odysseus. The roads that she chose to take in orderb to return to Ukraine; tricks that she resorted to in order to survive, to save her “gang”, to get closer to her vital goal – your regular Odysseus in a skirt, give or take!

The Jewish mother combines in herself qualities of protagonists of the picaresque novel as well as of the heroic epic. How could it be otherwise?

Speaking of my grandmother, she was the most fortunate of all the above-mentioned mothers, the only one who died in old age, in New York, at a safe distance from the stage on which the tragedy of the Jewish people’s extermination played out. I must say that the price for parting with one’s own identity turned into lifetime payments. My grandmother was afraid of everyone and everything: the neighbor-“goy”: the “eavesdropping” phone operators; discussing anything within earshot of a passerby. Not that she was afraid that her deception would be revealed (after all, her nationality was too evident, a proverbial Le Secret de Polichinelle), but she simply had grown accustomed to fear. On her tombstone, there’s her Russian name in English letters, and above it is a Star of David, a standard Jewish fare. At least that. I always forget to bring enough pebbles for everyone who’s already buried there, but hers is the first, the most memorable one.

A Jewish mother saves her children by devouring her own flesh.

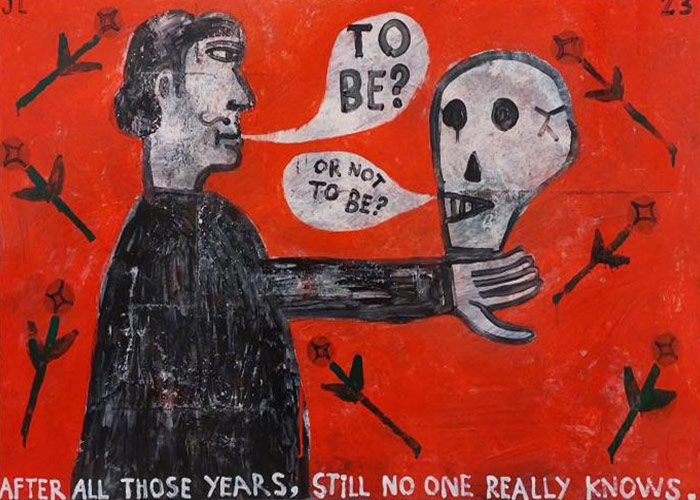

Primo Levi, an Italian Jew, a chemist who, after the war and the concentration camp experience, became a writer, in his collection of essays “The Drowned and the Saved,” analyzed the personal qualities of those few who went through the daily torture of the concentration camp and emerged. In his essays, he taps into the role of shame in the process of victimization of survivors. A mother who makes a shameful or otherwise compromising decision and takes responsibility for it, helps others to stay alive — not only physically. This also eases the future burden of shame for her surviving, maturing child. They call it “post-traumatic growth.”

An unexpected afterword is written by life itself.

The chronology of events is important here. All of the above was written in January 2022, and by the end of February I began to work with civilians in Ukraine, who, with the onset of war, found themselves in the role of those psychological children who needed to hear from professionals, “Do everything it takes to survive.” Presently, I, a therapist and a mother, tell young women and their children to “forget all the rules of behavior if they interfere with prolonging your life even for a day.” I talk to people in the occupied zones; I talk via unstable Internet. I talk to those trafficked to Russia, to those who try to get out of hell. It’s an amazing phenomenon, an amazing belief in the power of the superego. Such is post-traumatic growth, a messed-up punch line, an out-of-character solution. Here I am, dear G-d, the Jewish mother of the Ukrainian people.

Self-translated from Russian