An Apocryphal Essay

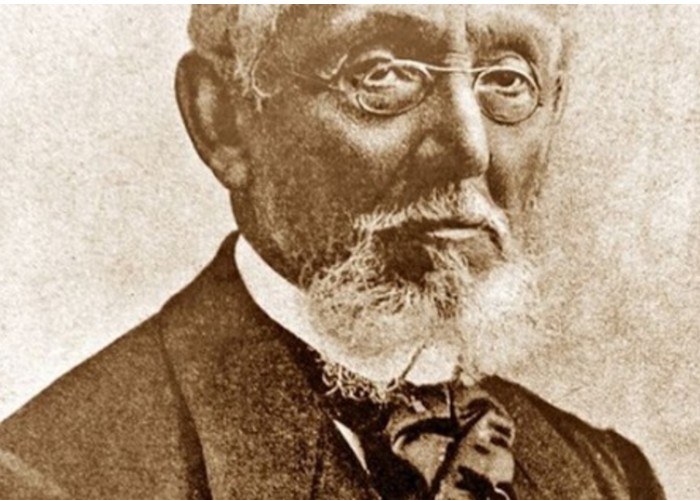

Leo Tolstoy wasn’t even-tempered. One might say, he was a bit contradictory. And to be honest, Leo Tolstoy had a bad temper.

Maxim Gorky came to Yasnaya Polyana and walked with the count for a long time in the surrounding meadows, trying to find out the secrets of his writing. After leaving the estate, at first, they usually walked along the road, and after passing a birch grove, they climbed a hill. Here they would take a break, and Tolstoy would perform a couple of exercises – he waved his arms and squatted, loudly crunching his knees, while Gorky stepped aside and lit a cigarette. From the hill, one could see a river, a skeleton of a burned-out mill with a black wheel, and an old humpbacked willow. The other bank, flat and dull, was filled with gardens, behind which could be seen the red roof of a barn and a well’s crane. Vegetable gardens spilled over into fields, which looked violet and somewhat ghostly; and on the horizon, a narrow strip of darkness was either a distant forest or a thick cloud filled with a July thunderstorm.

In the afternoon it got hot, and Tolstoy’s mood would deteriorate. Gorky, noticing this, became affectionate. This would anger Tolstoy even more. He would get thirsty, his shirt sticking to his back, and flies getting to him. Leo would turn gloomy, and walk faster, chopping off the heads of wayside burdock with his stick.

Gorky would follow, mumbling in his rounded baritone into the count’s back. Without turning around even once, Tolstoy either did not respond at all or responded only with interjections. He would puff and snort and quack. Gorky didn’t lag behind, pestered him with nonsense, joked, and laughed at his own jokes. He would ask something, without waiting for an answer, joke again, and laugh again. Tolstoy would just walk on. Swifts darted silently over the meadow, the west was darkening, a thunderstorm was creeping from the darkness.

“Lev Nikolaich, that dream of Anna’s … That dream where the dwarf forges iron and says something in French…” Gorky angrily slapped a horsefly on his cheek. “Bastard, sucking my blood …”

He wiped his palm disgustedly on his pants, still walking.

“So, I really want to know, Lev Nikolaich, what is the symbolism of that dream? Anna’s dream?”

The count suddenly stopped and turned around sharply.

“Do you really want to know?” Tolstoy asked glumly.

“I do,” said Gorky, baffled.

“You really want to?”

“Yes.”

Tolstoy grinned, scratched his beard, and spat into the grass.

“Then I won’t tell.”

* * *

Boring the reader is easy; all you need to do is tell him everything at once. This phrase was uttered by Anton Chekhov when he finally arrived at Yasnaya Polyana last summer. They drank tea on the veranda. It was August, the air was stuffy, flies were getting to them.

“This bastard was aiming at me, doc.” Tolstoy carefully removed a ladybug from his beard and threw it out into the garden. “The bastard.”

He thought about it but didn’t say anything. He just grunted and poured boiling water from the samovar into a glass. With his fingers, he pulled a piece of refined sugar out of the sugar bowl and dipped it into his tea.

“Smells like apples,” Chekhov snapped his fingers. “Is it saffron?”

“Devil only knows,” the count responded, jingling a spoon in his glass. “And you, Anton Palych, better help yourself to sushki. And to the jam, too – it’s gooseberries.”

“Am I allowed to smoke?”

The real Chekhov turned out to be totally different from his photographs, which depicted a weakling with a pince-nez and a goatee. This real Chekhov was half a head taller than Tolstoy himself, broad-shouldered, with an officer’s bearing. And his baritone was a pure jeune premier. Moscow women must be running after him in flocks. But where did he get the idea that my writing is boring? He must be talking about Anna; he himself, you see, doesn’t have the guts for a novel–stories and novellas are all he can pen. Or did he say that out of envy? Doesn’t look like it, though.

“The humidity…” Tolstoy moved the ashtray aside, lifted the sugar tongs, turned them this way and that, put them back on the tablecloth and some reason sniffed his fingers. “The stuffiness…”

“It’ll pour in the evening,” Chekhov took a tasteful drag on his cigarette and blew out the smoke aside. “It’s August…”

He wanted to say something important, something meaningful–on the way to Yasnaya Polyana, his thoughts formed into clever phrases – clear and honest, but now only lofty vulgarity, sticky and nasty, like honey and sand, came to mind. And this damn heat on top of it all…

“And you, Anton Palych,” Tolstoy asked with sudden enthusiasm. “Do you know how to swim?”

“Swim?”

“Well, yes, swim,” Tolstoy moved his arms like a bear wading through the bushes. “Swim!”

“I don’t even have a swimsuit…”

The Count muttered something disdainfully. He got out from behind the table, noisily–rattling a chair and clinking tea utensils. He stomped into the house and immediately returned with two towels. He threw one over to Chekhov and hung the other over his shoulder.

The weather was getting worse. When they climbed the hill, the sky was already covered with a gray haze, the sun became a round hole, bright, but not blinding. The heat seemed tangible, like in a steam room. Below the bend of the river darkened like tin, and a cloud, fat and shaggy, hung over the gray-yellow fields. In the violet distance, one could see the dark streaks of a shower, accompanied by a dull grunting.

They descended to the river along a curved path, dead clay with imprints of bare heels gleaming white like gypsum. Women with wet linen were walking up from below, pink and sweaty. They all fell silent at once and stepped aside, letting them pass. Tolstoy looked at the women as he walked, fixed his gaze on a strong young woman, who was dark, with heavy eyebrows; she glanced at him and turned away. Chekhov pretended not to notice, and for some reason, he began to whistle. In an early draft of “War and Peace,” there was an episode of Helene having fun with two Frenchmen at the same time, and when Sophia stumbled on it while copying, she said: “Ugh, Lyovushka, this is disgusting – it should be removed. Young ladies will be reading this. We must remove it.” So, he removed it.

The smell of warm mud wafted out from the river, and a new pool with footbridges peeped out of a willow. It smelled of fresh pine boards.

“The old one was knocked down last March.” Tolstoy pulled his shirt over his head. “Ice drift. Cut it off cleanly.”

Chekhov sat down on the bench, took off his hat, and put it beside him. He slowly unlaced his shoes. Tolstoy, already naked, crumpled up his clothes and shoved them under the bench along with his boots. Stomping loudly, he went to the footbridge. He looked around.

“Clothes go under the bench, Anton Palych! And cover them with a towel – it’ll pour any minute now! Cover them with a towel!”

He walked over to the edge and started funnily waving his arms, warming up. A skinny backside, a beard, gray hair – a spitting image of a goblin. His hands, large and bony, were brick-colored. Chekhov twisted his socks neatly and stuck them into his boots. The boards were almost hot. He got up and stretched, hesitating a little, then took off his pants.

A purple storm cloud has already covered half of the sky. It grew, and swelled, and its ragged edge curled overhead. A tough gust of wind washed over them with warmth and dust, with the spirit of dry grass. Ripples swept across the gray water, and the reeds bent down at once. The willows rustled; a shudder went through the gray underside of their small foliage. One drop splashed onto the planks of the platform, followed by another.

Tolstoy shouted something loudly and, pushing himself off, jumped off the footbridge into the river. He emerged, waved his hands, and dived again. A wave came; coastal water lilies nodded their yellow flowers in time. It was already raining heavily. Chekhov, stooping, went down the stairs into the water, lingering on the last step. He sat down, stretched out his neck, and swam. The sound of the rain was now a dense, thundering rumble.

Tolstoy emerged in the middle of the river, and it wasn’t a simple emerging but a powerful burst to the surface–with splashes and a roar. He screamed and snorted and waved his arms as if he were trying to take off. “Queen of Heaven! Ah, this is so good!”–-he repeated, slapping the water with his palms. He swam sazhenka strokes* to the mill – fishermen were hiding under the willow tree, and he talked to them. The peasants laughed at something, then pulled out a fish stringer with a huge pike from the water.

Chekhov swam gently, like a woman, to the middle of the river; there he turned over onto his back and, spreading out his arms like a cross, put his face to the rain. The current pulled him lazily southward. Raindrops tickled unbearably on his palate; Chekhov screwed up his eyes, and the downpour hit his forehead, lashed on his eyelids, and his cheeks. Through the sound of the rain, he heard: “Queen of Heaven! Ah, this is so good! So good!”

* * *

Chekhov left in the evening. He refused to spend the night, saying he had many things to do in the morning. Tolstoy came back to the terrace, followed the cart with his eyes, and when it disappeared behind the birches, he sat down in a wicker chair.

“What a man…,” he muttered, scratching the tablecloth with his fingernail, in displeasure. “He has the soul and the talent – he has everything… everything…”

On the train, Chekhov wrote: “It’s scary to think of the emptiness that will arise in my life when he is gone. It seems that I have never loved a single person so fully and so much.”

Chekhov will die first–in nine years.

“For me, the holy of holies,” he will write, “are the human body, health, intelligence, talent, inspiration, love, and absolute freedom – freedom from violence and falsehood, no matter what clothes they wear.”

He will die at forty-four years of age. Anton Chekhov.

Glory came to him early; people, total strangers, turned to him for help, for advice. He did not refuse anyone. An intellectual should be generous, he believed. Generous and modest: Chekhov read all the manuscripts that were sent to him, and he always wrote comments. He never denied anyone medical help; he never took money from the poor. He donated his fees to the construction of schools and the setting up of hospitals throughout Russia. Many of them still exist.

Good should be done secretly. Show-off generosity has a taste of boastfulness: virtue turns into bigotry, and a prophet turns into a bore. Chekhov never violated these commandments through word or deed.

In 1904, on the day of his death, Leo Tolstoy wrote in his diary: “I could not even imagine that he loved me so much.”

………………..

* sazhenka strokes (саженками) – an old Russian style of swimming

.

Translated from Russian by EastWest Literary Forum