Sochi was the same as ten years ago. And the ennui was the same too. Only now, it fit me even better. For some reason, I thought I had grown out of it, but it was either too big for me before or it was dimensionless. And besides, it was raining. I drank the rain out of a coffee cup, until a sign said “Hairdresser’s Shop,” where my gaze lingered. I went in and wanted to leave right away, because there was no one there, and just then a girl in a white coat appeared suddenly, a clean white mouse with a jutting out ponytail. She pointed at one of the three chairs. When I sat down in it, she asked:

“How do you want your hair cut?”

“I would like to shave,” I said.

She must have interpreted my words not as a request, but as a confession of a secret pipe dream. She stood looking out the window. Then she turned to me and said:

“I am an intern.”

“So?” I asked, trying to understand what her voice reminded me of, her way of looking at the rain. She looked out the window again and said calmly:

“I can cut you.”

At first I was frightened. I thought that she was really capable of such a thing, and not accidentally, but on purpose, that is, if she suddenly felt like it. But the next moment I smiled at the joke of my imagination. “Strange,” I thought, “that my mind hasn’t replaced “cut” with “stab”. Ridiculous.

“Do you have to warn me about this?”

“No.”

“Well, then don’t give away any production secrets.”

She swung and covered me with a sheet, shoved a towel down my scruff, and began to soap my cheeks, waving the brush hard. As she swung the razor over me, I asked:

“Who do you practice on? Do you have test subjects?”

“No, we practice on balloons,” she said.

“How do you do that?”

“Very simple. You inflate the balloon, soap it up, and then use a razor to get the foam off. If it bursts, the soap splashes in the eyes. That’s how we learn.”

“Yeah, it’s brutal — soap in the eyes.”

“But it’s better than if а client bursts, right?”

“So am I the client or the balloon?”

“If you talk, I’ll cut you for sure,” she said, and I shut up.

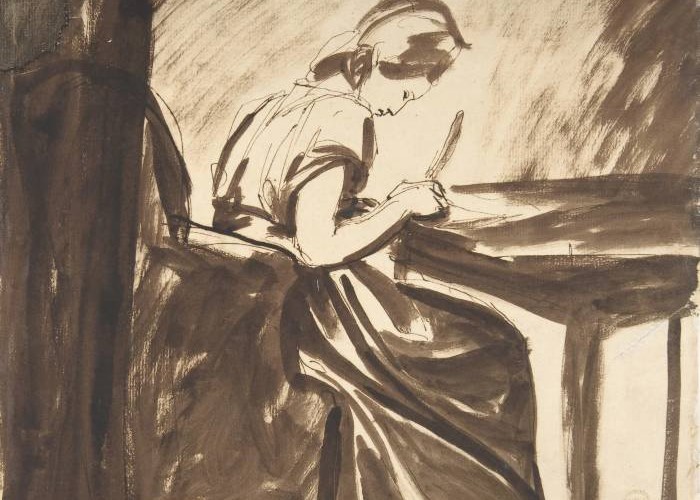

She slowly removed the foam with her razor and finger, and I closed my eyes and began to think of another topic for conversation. I wanted to talk to her and get acquainted, but, as luck would have it, nothing came to mind.

“Oh!” she exclaimed. “I told you…”

I felt nothing, but there was a red line on my white cheek. I sat there, fascinated, looking at my cheek. When I shifted my gaze to the girl, I saw that she was looking at the rain. “That’s sick,” I thought. Then she did turn to me. Apparently deciding that there was a need for moderation in bloodletting, she took a bottle of peroxide and a piece of absorbent cotton from the table. The blood was stopped. The girl offered to wash my bloody shirt.

I took off my shirt, gave it to her, and went to the other sink. I washed the foam and blood off my cheeks. There was still some stubble under my chin, but I thought that was enough experimentation for today. The girl was wringing out her shirt. I looked at her in the mirror. She looked up, and our eyes met. In the mirror. I said:

“Can I take you out someplace? Anywhere you want — I don’t know this town very well.”

“The city is full of people right now. They are left without sunshine and don’t know what to do, so they are out shopping. The best place to be is by the sea. There’s nobody there in this bad weather. We could go if you like.”

“Right now? Can you leave here?”

“Wait, I’ll change.”

The beach was indeed completely empty, and that made it seem wild, in spite of all its livability. The rain hung in the air, disembodied, invisible, a shy tickle that made you shudder but not laugh. The rocks rattled beneath my feet, and there was a low rumble, almost inaudible, the sky, like a slab of concrete, did not allow any sound to pass through. And the sea lived in that bag of stones. It was stirring a little, reminding me of my companion—lathering up the gray cheek of the beach, and immediately washing away the foam, and lathering it up again.

To make the resemblance complete, there were also mounds of cut black hair which smelled like algae during gusts of wind, when we were sitting in the first row of wooden beach beds.

She was constantly looking at herself—out the window, at the sea. But the sea was the most interesting thing, because there was the sea inside her, and not the one she was looking at, but the real sea, without shores. She couldn’t see it yet, but she felt

it more clearly, and so she looked at this blue model of herself… I was thnking all this out loud, while looking at the sea, and suddenly, she said:

“Yes, yes, that’s exactly how it is.”

I was glad I finally had someone to talk to about it. I wanted to say something to her, but suddenly I felt that there was nothing more to say, that my words were getting their inept feet on bare ice and falling down. All talk is an approximation of this, and we’ve already said it. I asked, just to keep the conversation going:

“Why did you choose this profession?”

“I don’t know… What difference does it make?”

She looked at me coldly. She realized that she had made a mistake, giving herself away to a stranger who had accidentally guessed what was inside her, and had not given it much thought, as if it was nothing compared to such things as choosing a profession. I didn’t know how to tell her now that… What? What could I say? So I remained silent. “She must sense in me the symptoms of her illness, and words have nothing to do with it,” I thought. I saw an old man walking slowly along the sea. He stopped, took a small black bag off his shoulder, tossed a bottle he had picked up under his feet, and walked on. He was still far away and seemed to be walking in place.

“I have some wine in my bag. Let’s drink it and give the bottle to that old man over there.”

She nodded. I pulled out the port and began to pull the plastic cork off with my flat key. The cork resisted as hard as it could and suddenly flew out. A red fountain burst from the bottle’s throat and poured down my companion’s white shorts and dark, thin legs. She laughed:

“This is revenge! Blood for blood!”

We drank the rest of the wine from the bottle. I put my arm around her shoulders and we waited for the old man, looking at the damp canvas that had three stripes on it—two gray ones and, in the middle, а blue one. The old man was now walking towards us, bent and withered, seeming more and more disembodied as he approached. Parts of him flew away like a dandelion’s as he walked on,. His head was shaking and he kept flinging the sack from one shoulder to the other. As he approached us, he took the bottle and murmured without moving his lips:

“Thank you. God bless you.” He went on, but suddenly turned around. “You are good people. I can take you with me when I collect the money.”

“What are you collecting for? Where will you take it?”

He looked at me in surprise and answered:

“A plane.”

“And how far are we flying?”

“To Mamayka. Will you fly too?”

“Of course!”

“I’ll find you,” he promised us and then turned and walked on to his nowhere.

I remembered about the flooded shorts and said:

“It’s my turn to do the laundry.”

“I’ll do it myself. On myself.”

“You’re not wearing a swimming costume?”

“You’re surprisingly intuitive! Are you always like this?”

“No.”

“But to me you will be forever. Let’s go to the sea.”

“You’ll freeze, wearing wet stuff will make you cold.” I kept making the same abrupt movement, trying to pull off my wet shirt. I succeeded only for a moment, and the fabric was clinging to my body again.

“It’s okay, I live here, not far from here. I won’t have time to freeze, let’s go!”

She ran towards the sea, but something kept me on land, and I remained sitting on the trestle bed. After five minutes, I undressed and swam, but she was already far away. Then I lost sight of her. I searched for her for a long time among the waves, until I realised it was pointless. I was not at all surprised by her disappearance. I wasn’t wondring about where she had gone—did she swim to another beach, did she drown, did she even exist at all? I was leaning towards the latter while walking to a train station under the bright Sochi lights on completely dry tiles. The whole day, with its rain and madness, was gone to waste, and I was no longer certain that I had seen anything in the city other than those lights. I boarded a passing train and went to a village on the outskirts of Greater Sochi. The carriage was empty. I took off my shirt, which still held some moisture. It was the only thing left from that day. I instantly fell asleep. I dreamed of an old man collecting bottles. He was leading me by the hand along the sea. His old hand held mine surprisingly firmly. Not that I was trying to break free.

_____________________

Translated from Russian by the author. The original of this story was published in Alexander Milstein’s first collection of stories “School of Cybernetics” (Olma-Press: Moscow, 2002).