1

Here I am by your side, a woman from a country of endless wars, an accursed land, a realm of mysterious killings, a world of charlatans where women are strangled, young girls are killed and other such horrors are commonplace. From a country where there’s plenty of grief, and plenty of joy. Oh yes, you said that being cheerful was never one of my traits! Okay, but what do you know of me to say that? There are lots of things I’m going to do that will surprise you. Believe me, they’ll surprise you. I swear, though I may look very serious on the outside, on the inside I’m light-hearted. I said ‘pass me that glass and you’ll find out’! You gave me your glass and I drank it in one swig. That day I very much wanted to get drunk.

What do you know of the violence I have seen? It’s true there’s violence everywhere and no one has monopoly on crime, but there is crime and there is crime. There are crimes motivated by passion, there are crimes motivated by ideology. With the first kind of crimes handsome men cause a lot of trouble.

“Do you think they’re handsome?” you asked me.

They wear smart, expensive clothes. They steal and corrupt women, or kill them because of love or hatred. Their lives don’t go any further than that. You could say that corrupting women is just as much a crime as murder is. Fanatics are more brutal. They kill children, rape women and corrupt the innocent. They impose an obscure way of speaking. Believe me, taking things seriously is often an important first step towards murder. It’s a holy act as far as they’re concerned, nothing else. It’s a holy act, holier than being a carpenter or a mason or a tailor or a plasterer or whatever.”

“Hey, let’s be done with that!” you told me.

Once I said to you, “It’s hard for me to express myself in a language that isn’t my first language. It’s something I can’t explain to you now, something I understand and feel, but it’s hard for me to put into words.”

I remember that day very clearly because it’s engraved in my memory like a lantern on a dark night. You had asked me to take off a hair band to let my hair blow loose in the sea breeze. You had taken off your sandals to feel the warmth of the sand on the beach path. My cotton skirt was flapping in the wind and you said ‘leave it so that I can see your brown legs every now and then’. Maybe you no longer remember that incident, but I remember it well. It’s imprinted in my mind. Your skin that day was radiant and glowing, and you were laughing. We were so close to each other than we couldn’t see each other. We were both absorbed in each other, in each other’s warmth and smell, mixed with the smell of the sea. Your left hand was on my hip, and you were devouring me with your eyes. Yes, I remember that incident well that day. You know I have good memory. You’ve told me that yourself several times.

You said, “Sophie, you have good memory. You even remember the tiniest details!”

Yes, I remember even the tiniest details clearly, as if they had happened now, not in the past.

I haven’t forgotten Jamila, the girl who was with me at school. I’d known her from childhood because their house was close to our house. Her long black hair, her slim limbs, the pallor of her face, which set off the black ribbons she wore. All this drew me to her. Unlike the others, who made fun of her for being so thin, pale and weak. I loved her sickly appearance, which made her look ethereal and angelic. We suited each other, and together we played truant from school. We wandered round the market and the streets in town. I was strangely in love with her and I wrote her many passionate letters. The intensity of my love surprised her at first but later she sincerely loved me in return.

Her father killed her mercilessly. He hit her on the head with a rock and she died. He killed her because our neighbours’ son had raped her. He raped her and ran away. She came back home terrified and without understanding what had happened to her. With childish innocence she asked her mother why she had blood between her legs, and her mother slapped her and told her father. The mother wanted to erase the shame by killing her.

When she died, I could sense her soul leaving her body at the very moment it happened. I would get up in the middle of the night, frightened and trembling. I had seen her disembodied spirit in the darkness and heard her voice calling me by name. I felt her spirit walking there, beyond the window. I pressed my face to the window pane and stared into the distance. I waited for her but in reality, there was no one there. There was no one beyond the window, nothing but some trees with their branches swaying mysteriously. Nothing but the summer clouds that covered the sky like smoke. The stars in the sky had disappeared and I could no longer see any light in the street. Nothing but pitch dark, like the darkness in my heart. Suddenly I thought I heard her faint, pale voice from far away, but gradually coming closer. It was the same voice that used to call me for help when boys surrounded her and were trying to hurt her. When her voice faded away, I knew, I don’t know how, that my past and all my memories were disappearing with it. All my happiness disappeared with it. Everything I had loved and treasured. With her departure everything said goodbye to me, then and forever. I said goodbye to all the happy moments with her that had gone by in a flash, and I went back to bed, wrapping the blankets around me as if I was being buried in a grave.

In the morning I cried for her with indescribable bitterness and pain. I still mourn and weep for her today. Her silent, humble presence, which made me feel safe, has gone forever. Without her I was friendless. For years after I lived in terrible isolation, until I saw you. Your presence in my life has brought back all those happy times I had with her.

Another thing I won’t forget is my mother’s trembling voice at night. I wrapped myself up in bed and pretended to be asleep. “Don’t hit me in the face,” she said to Radi, the man she had married after the death of my father.

She tried to turn her face in the other direction but he pulled her with a strong, calloused hand and brought his other fist down hard on her face. Blood streamed from her nose.

“Whore, you whore,” he said. “Say you’re a whore. I won’t let you go till you say you’re a whore.”

“The girl’s asleep and I don’t want her to hear this,” she said.

The smell of alcohol mixed with garlic filled the room. Just because he was drunk, it didn’t mean he hit her with less force. “Say you’re a whore,” he repeated, in a steady, relentless voice.

“Radi, the girl’s asleep. For God’s sake, I’m worried she’ll wake up.”

“Your daughter’s going to be a whore like you. A dirty rotten whore. Get your hand off your face or I’ll kick the girl in the stomach.”

“Leave the girl alone for God’s sake.”

“Get your hand off your face.”

She took her hand slowly off her face, and he took her by surprise with a pitiless punch in the teeth. She screamed in pain. Blood poured from her mouth and ran over her chin onto the pillow. She was worried she would let out another scream. She held it back, stifled it inside herself. She thought I was asleep and she was frightened of waking me up.

She never spoke to me about him. She was always avoiding me, hiding her blue bruised face and her bloodshot eyes in the morning. Maybe she took revenge on him the day he died. A wall fell on him in an old house while he was gambling with friends. When news of his death arrived, she didn’t speak, not a single word, and I didn’t see any tears on her hollow cheeks. She was standing in the middle of the house, immobile in front of the stove, holding a large ladle in her tired hand and steadily stirring a pot coated with soot. The pot was full of a yellow broth, always without meat or tomato paste. Her other hand was on her hip. Her face was pale and sweaty. Her eyes were sunken and swollen, but she continued with her work.

I looked at her. I wanted to find out how she would react. Secretly I wondered how she could eat at such moments. She looked directly at me, a look I recognized in her. “From now on, I won’t let any man hurt you. As for today, I can tell you, his death won’t ruin our lives,” she said, calmly and wisely.

She picked up the pan and went into the other room. “The death of a man in this world won’t spoil the broth,” she added.

I lived in hard times, my dear. I’m from a land that’s as rugged as a farmer’s hands. The sands are cracked by the glare of the cruel heat. A land of desolate hills, with rocks that shield the horizon, so that people can see only themselves. A land where coarse men livecoarse lives and glower like clouds that linger close to the ground, and the oppressive climate gives them only archaic melancholy customs, because they can make a living only by violence and through delusions. But life was a rarity that no one dared to touch because it led to death, and it stood apart like an abandoned cake.

Life was an ordeal. We were short of love and of food, watched by cruel fanatical gunmen, tormented by the biting cold of the climate, without any soup! The need for love was very great, because people’s feelings became like rocks! Since an iron wall was built between men and women, unmarried men found what they wanted by sleeping with animals such as donkeys and cows.

What can I tell you, my dear, about those days, about the moment when we heard that the fanatics were going to come into town by night, and panic crept in everywhere and the men gathered in the house of our village chief, who was a wise old man. That day the men started running around in vicious circles like headless chickens. They didn’t know what to do. No one could stand up to the fanatics.

Then the village chief came to our house. He stood at the door with my father, trying to shoo away a fly that was buzzing rudely around his nose. He was moving his jaw nervously as he spoke, then he wiped his wet hands on his black jelaba, and said to my father, “We’ll resist them.”

But my father left him and went into the house nervously. My father had a big grudge against the rulers and blamed them for his poverty. He almost gave up hope when he thought bitterly about how conflicts were taking the country backwards. He almost ended up shouting at the walls in the house because no one would listen to him or answer him, and he got lost in a wasteland of rancour and hatred.

At night, when the donkeys started to bray and the dogs to howl, the militiamen quietly attacked the village and took complete control of it. My father soon decided to join them. The muezzin gave the call to prayer while my mother was trying to persuade him not to join them. But he went into a long silence. His face that day was a blank canvas that didn’t convey anything – frowning, silent, severe and completely incomprehensible.

“What can I do here?” he shouted at my mother one day. “Stay in this impoverished village to chase flies?”

He brushed the dust off his jelaba and went down the dusty road that led to where the militamen were.

Night rose like a storm and swallowed up the small village. We could hear the wind in the trees and hear it sighing in the long grass.

One day my father came home early and said we were going to move somewhere else. I didn’t know why he didn’t say more than that, but later I saw him discussing things with my mother in the other room. My mother was anxious and frightened. I asked my mother what the matter was but she didn’t say anything. The next day we moved our things to the other side of the village. We went to live in a large house where the militiamen had been staying. They looked strange, they wore strange clothes and turbans on their heads. They scowled and had long beards. In the house there was a large room where food was served in large quantities, always accompanied by loud shouting. Behind that room there was a long room for women who wore niqab, and my mother’s job was to clean the whole house from morning till noon, then we would move to a small house attached to the same building, rather like a pen for animals where we slept and ate. My mother and I stayed in this small house but my father stayed in the big house and didn’t come back. Maybe he was doing other jobs that the armed men gave him to do.

I had to help my mother with the cleaning and other chores. We got up early, before everyone else, and cleaned the house from top to bottom. You can’t imagine how tired my little hands were, and my body and my feet.

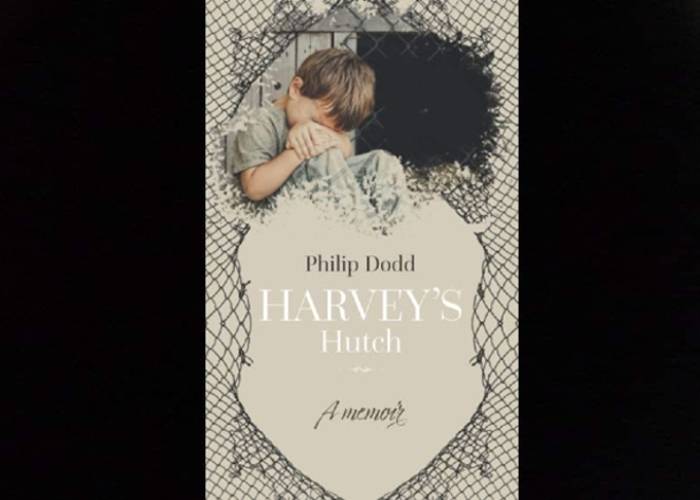

This novel was published, in Arabic, in Beirut in 2015; it was translated into English by Jonathan Wright.

~ ~ ~

About the novel: The Infidel Woman /The Godless Woman is the story of Fatma, who changes her name to Sophie. Fatma lives in a village near a small, remote town on the edge of the desert. The village is controlled by a fanatical militia that imposes its own laws on it. Fatma’s family takes sides with the militiamen, and Fatima and her mother work as servants to them. After her father dies in a suicide operation, Fatma marries a young good-for-nothing unemployed man who comes to the conclusion that the only way he can give his life meaning in society is through a suicide operation. He thinks that will transform him from failure to hero and win him entry to Paradise, where seventy houris await him. After her husband is killed, the militiamen decide to marry her off to one of their members. She flees to Europe through a smuggler who rapes her on the way. She arrives in Brussels, throws off the niqab and changes her name from Fatma to Sophie. She now has two personalities – Fatma, who works in the morning for a cleaning company, and Sophie, the young European woman who goes to bars every evening and comes home with a handsome young man as a form of revenge on her husband. He told her he was carrying out the suicide operation in order to have seventy houris in heaven, so she decides to sleep with seventy men in Europe. But she happens falls in love with a young Scandinavian called Adrian, an aeronautical engineer. She has a complicated love affair with him and often travels with him, but then she discovers he is married and has two daughters. At first, she accepts this situation but later rebels against it. She wants to keep him all for herself. One day she argues with him before a party they’ve been invited to. He leaves the house in a temper and has a car accident. He is hospitalized, in a coma. Sophie sits by his side, and tells him her life story.