XVI

Home means to my father. My mother died a long time ago. I have always been an orphan. Affection, tenderness, and warmth weaken character.

They indicate poor upbringing. They are petit bourgeois.

When I was eight, I got a wristwatch. It’s the only birthday I still remember. Otherwise, birthdays were like any other day. One just got something that one needed anyway.

I never got what I wished for. One shouldn’t spoil an only child. Should not endanger it. Should not let it slide into the petit bourgeois, selfish behavior. The girls in our building all had such beautiful doll carriages. I, too, longed for one of them.

Romania’s relations with China were still good back then. That could be seen in my toys. I had lots of mechanical toys from China, which my Mother was proud of. I was not yet political when I was six or seven, and I didn’t want to know anything about propaganda and good relations with Communist China. To me, a doll carriage, like the one Juliana got, a doll carriage from Germany, seemed much better, just what I wished for.

Both of my parents explained to me that more understanding was expected from me than from other children. That I had to learn to abstain and not give in to every whim. Be my own master. Control my- self. Show my strengths. Because we were supposed to be the New Humans. The people of the New Era. Stronger than nature. We, children of the Party, had to be an example for all the others.

I don’t know whether all of the children of the PCR block got this lecture. But at some point, all of the girls had these damned doll carriages. These capitalist white carriages. The ones that promoted comfort, laziness, and degeneracy. And at some point, I, too, got a buggy.

A buggy. A green one. So toilet-door green that I was ashamed. I should have been ashamed anyway, Father said. Because I couldn’t abstain. It was bad enough that Juliana’s parents had relatives in the West.

I don’t know whether the fall of Communism had already been determined at the time when little girls of the PCR-Block got their decadent doll carriages. You’ll see what will become of your daughter if you grant her every wish, said my father when my mother got weak, gave in, and bought me a doll carriage. A buggy. A green one.

I had given up on wishing very early on. Chinese toys, I did not want them. I wanted a doll carriage and a simple doll tea set. But I never got that. I wanted none of those flashy things that were in our glass vitrines. I had never been asked, and so they came as a surprise. Aren’t you happy, Mother asked.

I’d given up enjoying things very early on. The bear with the drum that I had never wished for. Not even the bear with the camera. Nor the ice cream vendor with his truck. Nor the Chinese man with the bicycle. And none of those objects that one had to wind up with a key, so that they circled on and on in their narrow world, always frozen in the same position. With a raised hand. With a camera in front of the eyes. With a drum in the air.

I had never wished for any of these toys, even if Mother was so proud of our collection. I was allowed to take it out of the glass vitrine, and show t when someone came to visit. But that rarely happened. Otherwise, I was not allowed to play with them — they shouldn’t break.

China, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and so on. One would think the entire Communist bloc was in agreement. This was before the Prague Spring. But even we children of the PCR-Block knew that wasn’t true. Radio Tirana spoke of the imperialistic Soviet Union and the revisionist Chinese. I can’t remember what Father thought of that. Mother’s thoughts, however, I remember. These little Albanians were paid by the Russians to emphasize freedom of expression in the Communist bloc. To display democracy. These little Albanians. They exaggerate. They take themselves too seriously.

The mood against the Russians began to spread more and more. Once the liberators had left the country, the murmurs became more and more distinct. That the Russians had taken away our agricultural products, mineral resources, and oil. As long as our oil was still there. Afterward, we reimported our oil. Only slightly more expensive murmured the voices.

What the Chinese got from us, I didn’t know.

But I knew that our Chinese brothers made lots of toys. Very efficiently. By hand. So that the children of their comrades in Romania would have something to play with. And so that millions and millions of little Chinese people could get work and eat their daily rice with chopsticks. So that every Chinese person could get a new suit every year.

That is Communism, my father said.

My friend Melitta and I listened to him with our mouths agape in amazement.

Romania’s relations with China were good back then.

They were even good when the new General Secretary of the Communist Party proclaimed himself President, the proud man who brought us the New Spirit from China. The Cultural Revolution. A gift from Mao. Shortly after the Prague Spring. A gift from professional revolutionaries. With a trip to China, our fraternization with the Giant Brother began. From then on, every little Chinese man was the brother of every little Romanian. But of course, some Chinese went away empty-handed. There were more and more jokes about the Chinese in Romanian folklore. And that indicated a kinship. A kinship in suffering. Only the little Chinese people were much worse off.

But when one wanted to point at someone even worse off, there they were. The Albanians. The Cultural Revolution had to be strictly protected. That’s why censorship was reinstituted. We had to build a Chinese Wall. But that didn’t fit with our Specific Național Goal. National pride had saved us once again. It stayed with the barbed wire. Vigilenţa. Vigilance. Death. Gray. Depression. Hundreds of words were banned. It was a positively minded society that threatened us. With negative effects.

Times have changed. Being connected to the outside world was suddenly a brave act.

Translated from German by Elena Mancini and Catharine J. Nicely

__________________________

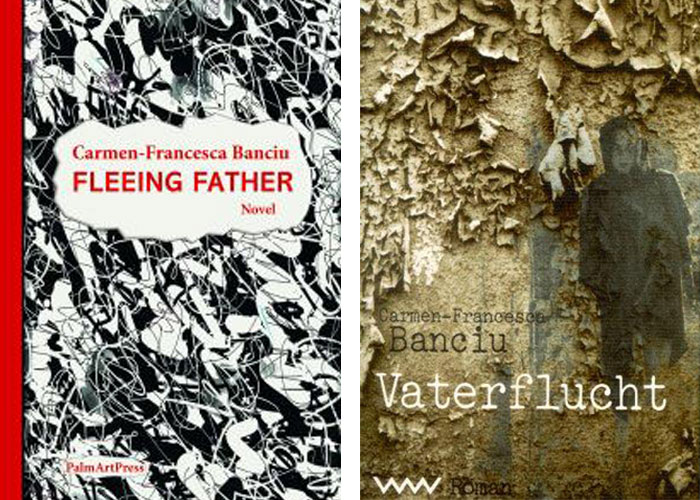

About the novel:

Fleeing Father / Vaterflucht is the first part of Trilogy of the Optimis by Carmen-Francesca Banciu, a German Writer of Romanian origin.The novel was written in German. When the precocious daughter of a high-ranking Communist official rebels against her patriarchal father and renounces the preordained path of the New Human – the ideal citizen who would embody the qualities needed to fulfill the vision of the utopian Communist system in Romania, she comes to a point of no return. Fleeing Father chronicles the courageous journey of a young woman’s struggle for freedom and individuality under the Communist regime in Romania. Through art and sheer strength of will, she resists the extravagantly cruel dehumanization wrought by the ideology she was made to represent and achieves selfhood – with all its concomitant triumphs and losses. Banciu’s hypnotic style and sparse and unsparing language is eloquent and emotionally penetrating and speak to all those who, at one time or another, had sought self-discovery, forgiveness, and a hope of healing in the face of psychological and ideological divisions.