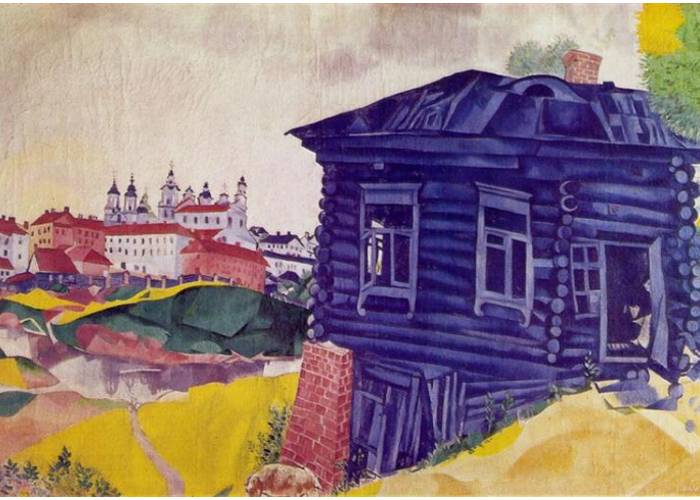

Everyone in Krasnopolye called her Old Countess. They said that before the revolution she really was either a countess or maybe just a landlady. She was German. Her name was Mrs. Greta. No one in the village remembered her young: to everyone she was “the Old Countess”. Before the revolution, she was either a countess or a landlady.

After the revolution, Krasnopolye was literally cleansed of local nobility: some were arrested, others were killed, still, others had managed to escape, and only the Countess remained untouched for whatever reason, while her estate was requisitioned by a local collective farm. Maybe because she was very old then, or maybe, as they said, her brother was some kind of higher-up in Germany and helped the revolution with money, and she received a telegram from the most important leader of the revolution. However if that were true, the next leader would have done away with her so that there would be no trace of her. Be that as it may, she was untouched by the revolution and afterward. She lived alone on the edge of Krasnopolye, her kitchen garden cutting into Malastovka village, her former estate. No one knew exactly how old she was, but it was clear that she was very old, and she probably wouldn’t have lasted this long alone if it hadn’t been for Elka, the red-haired niece of Dvosya the tailor, a neighbor. Elka was the daughter of Dvosya’s brother Abram, who for a while was a big boss in Kostyukovichi, and when he was arrested and his family exiled, the five-year-old Elia was somehow miraculously brought to Dvosya, joining Dvosya’s large family.

Elia dreamed of being a German teacher, like her mother whom she did not remember. When she was a little older, Dvosya set her up with Greta. And Elka became a kindred spirit to the lonely old Countess, “her Elsochka”, as the Countess called her in German. In return, Elia loved the Countess like her own grandmother. Dvosya was burdened with a large family: five daughters and a crippled husband, so it didn’t matter, as long as everyone was fed, thank God for that.

Elia stayed with the Countess all day, helping her with everything. Greta never talked about herself, but one day, when Elia was organizing stuff in the Countess’s trunk, she came across a little pendant with an old coat of arms on it, Greta said that this was their family coat of arms. And that’s when Elia realized that Greta was a real countess and that her nickname was not a joke made up by some local wits. By the way, we must mention a young history teacher Valentin Petrovich, with whom all the high school girl students were in love. And at every lesson, this Valentin Petrovich would remind Elia that her connection with the Countess, a bourgeois underdog, was a disgraceful stain on their Soviet school and that his Soviet conscience could not allow him to give her a grade higher than a “C” for history. Elia’s friends laughed, saying that this was Valentin Petrovich’s way to express his love for Elia, but Elia was frightened by his words, and the C’s in her report cards did nothing for her dreams of becoming a teacher.

But it turned out that C’s in history were not the main obstacle on the road to her dream of becoming a teacher, and that there was a more terrifying and ruthless obstacle – war!

The war came to Krasnopolye with a flood of refugees who were fleeing deep into Russia. The Jews of Krasnopolye were almost the last to join this human flood, either because of their naïve hope for a quick victory of Stalin’s falcons or an equally naïve belief in civilized Germans. Dvosya hesitated for a long time, not knowing whether it was better to stay or to run away with her completely unportable family and she even sought advice from Greta, who did not hesitate to tell Dvosya that they should all run away as soon as possible. Elia looked at the Countess in amazement and could not understand her words: after all, hadn’t she been telling them good things about the Germans all these years?

“The Jews will be killed: the evil spirit of the Nibelungs is released, and it rules Germany,” said the Countess. “Else, my granddaughter, listen to me, take your mother and run.”

“You should come with us, too,” said Dvosya, feeling confused.

“I must stay,” Greta stopped her, “I hope that my son Paul will come with them.”

“Your son?” Elia was surprised.

“Yes,” Greta nodded. “He was staying with my mother in Cologne when the revolution started. So he just stayed there. I haven’t seen him for almost thirty years.”

Dvosya was almost the last one to leave the shtetl. It was rumored that the German landing force had already occupied the Cherika road. But by some miracle, Dvosya’s whole mishpocha reached Krichev safely and got into the last freight train, which was leaving the already burning station. Elia helped everyone to get on the train but stayed at the station, saying that she would return to Krasnopolye because without her Aunt Greta would surely die and wouldn’t be able to continue waiting for her son.

“Tocherke, vos du tuts?” (Daughter, what are you doing? -Yiddish), Dvosya wailed. “The Germans are already there!”

“Aunt Greta is also German,” Elia answered.

It took her almost a week to get to Krasnopolye. Just like Dvosya said, the Germans were already there. The occupiers were represented by one low-rank officer, probably chosen given the insignificance of the shtetl, and by two elderly soldiers. The executive force of the new government was the police, drawn from the locals, and the village head. To everyone’s surprise, the head of the police was Valentin Petrovich, the history teacher.

When Elia returned, all the remaining Jews had already been moved to the ghetto, a small, narrow street at the edge of the shtetl. Houses of the Jews had been occupied by settlers from the surrounding villages and the local authorities.

The week Elia was away, Greta had given up on living. Before, she was still able to move around a little; now she could barely even sit up. She was surprised to see Elia. Her sunken eyes looked at Elia with fear:

“Granddaughter, why did you come back?”

Among all the bad news Greta told Elia, there was just one that was fairly good: the commandant of the shtetl promised Greta that, as an ethnic German, she would get a housekeeper from the ghetto, and that they would help her to find her family in Fütherland.

And so, Elia became the housekeeper. Greta begged her to go outside less often, but she had to go out for food, and one day Valentin Petrovich saw her and said, with a smile, that the Countess was not exactly eternal and that a moat behind the shtetl was waiting for the Jews of Krasnopolye. In the meantime, Greta was getting weaker and weaker. One day she asked Elia to give her a pen and paper. She was writing for a long time, then she put the sheet of paper in an envelope, wrote the name Paul von Dietrich on the envelope, and asked Elia to give this letter to her son when he arrived here.

“You should give it to him yourself,” said Elia.

“Oh, if I could meet him myself, I would not have written him this letter,” Greta smiled sadly. “My time is over.”

Two days later she passed. That same evening Elia was taken to the ghetto, and a few days later the Jews were made to go on their last journey. The commandant delegated the entire operation to the police, ordering them to save the bullets by making do with manual means. The commandant himself limited his job to inspecting the column of the Jews from the porch of a house that served as his office. Elia, standing in the front row, suddenly realized that these were her last minutes, and she remembered Greta’s letter. She took a step forward. They shouted at her, a policeman tried to push her back into the column, but the commandant, recognizing Frau Greta’s maid, asked her what was it that she wanted to say. And Elia, in German, managed to convey Greta’s request.

The commandant took the letter and promised to pass it on. Elia went back to the column.

They were taken to a ditch behind the shtetl, near the drying plant, and ordered to undress. They were led to the ditch in groups. Her former history teacher placed Elia at the end of the bloody conveyor belt. It was more terrible to be at the end of the line than in the beginning, and he knew it. The dance of death lasted a long time, and Elia, with her eyes closed, stood amid this terrible feast, waiting for her fate. Suddenly, amidst the groans and screams, she heard the screeching of a car, as its driver was hitting the brakes. She opened her eyes and saw a black Opel surrounded by motorcyclists. An officer literally jumped out of the Opel, and the police chief, not understanding anything in German shorthand, began to explain that the commandant’s order was being carried out to the letter: they were making do without bullets, and, wanting to show Mr. Officer how cleverly they were making do, he took an axe from one of his assistants, ran up with it to the thinning crowd of the doomed, and pulled out of it… Elia. The girl cringed, awaiting her end, but the officer began to shout. His words could no longer reach her, and suddenly she heard a word she recognized: Elsa. And then it suddenly dawned on her who the officer was.

“Paul!”

“O, mein Got!” the officer exclaimed, and ran up to Elsa, shoving the chief of police aside. “Ich Otto! Paul mein Vater! Die Grossmutter hat uber dich gesschriben. Du Deitsche! So die Grossmutter gesagt! Behalt! I am Otto! Paul is my father. Grandmother wrote about you. You are German. That’s what Grandma said! Remember – you’re German!” He repeated the last word twice.

Elia wanted to say that she was Jewish. But her tongue was not working, her legs buckled under her, and she fainted. She came to in a car, wrapped in an officer’s overcoat, and Otto, who looked remarkably like his grandmother, was sitting next to her.

After the war, when Dvosya returned to Krasnopolye, her neighbors told her about Elia. Their stories were tangled and mysterious, but Dvosya was afraid to ask for details. Those were not the right times for asking questions. Valentin Petrovich finished serving his twenty-year term and came back. He did not brag about his exploits, but when he was drunk, he would always say that Elia and Greta were German spies.

Translated from Russian by Nina Kossman