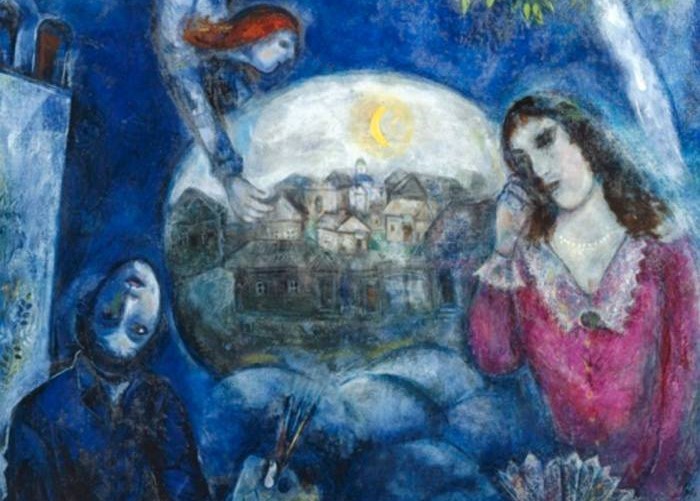

“Who is like G-d?”—that’s the meaning of Michael in Hebrew. Yet the god narrating this story carries a death sentence. He doesn’t rule the world; he can’t even control his bladder.

After the examination and biopsy, they handed me my diagnosis. The urologist at the district clinic, a sort of languid middle-aged man, glanced at his papers and declared: “Nothing to celebrate here.” A proverbial black cat of despair raked its claws across my soul. Need I tell you how big that cat was? As for my consciousness, it was now clouded and depressed. Alcohol would help me sleep for a few hours. But a choice had to be made: spend my nights wandering in the void between panic and hopelessness —or surrender to cognac? For a week, I chose the second option. I needed that time to map out the new rules of my existence.

I had to keep up with my colleagues’ jokes, hoping they wouldn’t sense the shift in me. How could I remain the boss who knew what, when, where, and why—who ensured the gears kept turning, leading us toward some collective success, an end goal, or whatever you want to call it? And how was I, with all that in mind, supposed to sit there humbly in the clinic’s waiting room, moving from the receptionist to the doctor, the professional who would decide my fate?

And so, at last, I made it to the specialized medical center, where I met a young woman. The doctor glanced through my paperwork, pressed her finger precisely where her medical knowledge and experience dictated, and asked, “Do you understand your diagnosis?” I named it plainly. I had to show that I was in control of something—however small—at the very least, my composure. Two existential questions loomed: To be or not to be? and Has my manhood—or perhaps even my life—already run its course? Inside my mind, they wrestled like fierce opponents—slaps, throws, brutal collisions. And then came a third: How many shots of cognac would either knock these sumo wrestlers out—or at least convince them to take a break?

“Tough day, Mondays,” the next doctor remarked offhandedly — the one tasked with venturing into my inner world and cutting away what, in his view, was causing me trouble. Instead, he scheduled my hospitalization for Tuesday.

That left me with four days. My wife knew what was happening. I told her, “Do what’s best for you,” hoping she would choose to stay by my side, just as she always had. And she did—which lifted my spirits, if only a little. As for the children, they were told, without much detail, that Daddy had to go to the hospital. They took it with understanding and quiet empathy.

With the rise of social media, it has become increasingly common to see posts—both photos and heartfelt tributes—about the passing of loved ones. But I’ve always preferred to feel the warmth of my family while I’m still here, rather than be met with a self-indulgent post: “How will I go on without you?!”

The day before my surgery, I gathered my colleagues and told them it was time for me to take care of my health. To cut off any further questions, I added with a touch of emphasis, “Everyone gets sick. Why should I be any different?”

Operation

Humanity will wait a long time yet for the words of the prophet Isaiah to come true:

“They shall beat their swords into plowshares,

And their spears into pruning hooks;

Nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

Neither shall they learn war anymore.”

A war raged in the neighboring country. Innocent people were dying. You turn on the news, hoping to hear that the madness has ended. Instead, men and women in expensive suits and religious robes continue to explain why this is the proper way to lighten the burden of the earth.

Receiving your diagnosis only increases your perception of impotence. You reach the grim realization that you have no control over anything—not over the world you live in, not even over yourself. How can you make the world a better place when you yourself are in need of serious repair, and even that repair comes with no guarantees? One thing, at least, is certain: just when you think you’ve hit rock bottom, someone quietly knocks from below…

It was in this state of mind that I found myself in the hospital’s emergency room. I received my number for the queue. Along the way, I read the signs marking the various departments: Endoscopic, Radiological, Oncosurgical. One door bore a sign that read Enema Room—something crude, perhaps, but not dangerous.

Soon, changed into hospital attire and officially registered, I arrived in a two-bed room. My roommate, as it turned out, was an elderly man who longed to return to his dacha, where he lived year-round and where, in winter, the air “rang like a bell.” In the past, he had served as deputy chairman of the Union of Composers of Belarus. “Nobody needs that anymore,” he lamented. “These days, the music they play is foreign, pop, lighthearted—whatever sells the most concert tickets.” A tube protruded from his body, a silent marker of his post-op state.

In the next room lay a young man—37 years old, tall, with a sculpted torso. The following day, two nurses arrived, joking as they ordered him to strip and lie on the gurney, as if trying to lighten the mood. Then they wheeled him off to the operating room.

A few hours later, they brought him back—conscious. For 24 hours, he lay there silently, without a whimper. Then he got up and started walking. Like my elderly roommate, he too had tubes protruding from his body, discreetly tucked away in a polyethylene bag.

I took note of all of these details knowing that something similar awaited me. When you are told that for lunch, you will get only soup, and for dinner, just water, and in the morning, nothing, you understand that tomorrow, they are coming for you.

And they did come—two women in white, a nurse and an orderly. My last attempt to keep something on, “at least my glasses,” was rejected. I climbed onto the gurney, naked as the day I was born, and was covered with a sheet. I was handed a vial filled with something unknown and told to keep it upright. And so I went, holding the vial like a candle.

Perhaps I would’ve preferred to have been conscious and in control during the operation. But that was not in the cards, and for that reason, I can’t say how it went.

Here and Alive

Happiness came during my tongue-tied come down, just to be alive. The painkillers prompted a sort of clear and giddy mental space.

What was upsetting though, was the drain sticking out of my side. The catheter upset me even more. What customer service, you don’t even need to run to the toilet; for this, a plastic bag was attached to the other end of the little tube.

My doctor would pop over, never lingering for more than a few minutes, as he’d be busy with operations. He’d ask and answer questions, look me over. Surgeons are there for surgery, not psychotherapy, though I wouldn’t have minded some.

The nurses did their injections, gauzed me up, sanitized the stitches, measured my temperature. The orderlies kept things in order. The food was mediocre, but that didn’t matter as I had no appetite.

Great joy came for the first time when they said I could shower. “Can I really?” I asked in disbelief. “Am I allowed… everything?” There are those who dream of a second Chateau on the Côte d’Azur. All I wished for was to stand under the warm shower streams in order to believe that a return to normalcy was possible.

Soon the drain was removed. A young nurse took out my catheter. She did it efficiently, quickly, compassionately. Where did my self-consciousness go? I stripped naked, let her rub my intimate parts with sanitizer. They took out my tubes.

The doctor announced my discharge date, for ‘further recovery at home’. My former life awaited me. The hospital, which I now knew intimately – is a factory of health, a place where people are healed and saved, and even tumors and excess are removed. Here there’s less pretense – weakness is not something to be ashamed of in a hospital. It’s a place of truth. Illness will reveal if your loved ones truly love you.

Life is beautiful.