Old Griet was grumbling. The master has completely lost his mind. Yesterday, as she peeked into his study, he was jigging up and down with excitement, crying, “This little thing looks like a slipper! By God, it’s like a tiny slipper!” He held one of those bizarre metal things of his, two plates and a piece of small glass between them that he was so fond of making lately. He closed one eye and was looking into the glass with the other, choking, gasping with agitation.

He looked crazy.

And the other day he bid her to come closer and to open her mouth. She faltered but he said softly, “Don’t be afraid, I am not going to hurt you.”

She reluctantly opened her mouth and he quickly poked in it with some stick. She felt a taste of metal on her tongue and wanted to spit.

“There, there!” said the master, wincing. He turned away and started looking into the small glass.

“God Almighty!” he cried so loudly that Griet jumped aside. “It’s a menagerie!”

“What?” she said in fear.

“You’ve got a whole menagerie in your mouth, Griet!”

She thus realised that he was off his head.

That afternoon she told Bea about this. Bea, a kitchen maid, was young but nevertheless revered by other servants for her wisdom.

“A menagerie?” said Bea. “Like animals in cages?”

“Yes! He said so!”

Bea started laughing. She was snorting like a horse.

“You’ve got a mouth full of caged beasts!” she was saying between bouts of laughter. “Tiny beasts in tiny cages!”

Griet gave her a long look.

“They say you are wise,” she said at last, “but you are just plain stupid.”

“You are the one who is stupid,” Bea retorted.

But Griet knew she was not stupid. It was that nutter, her master. He completely lost his mind.

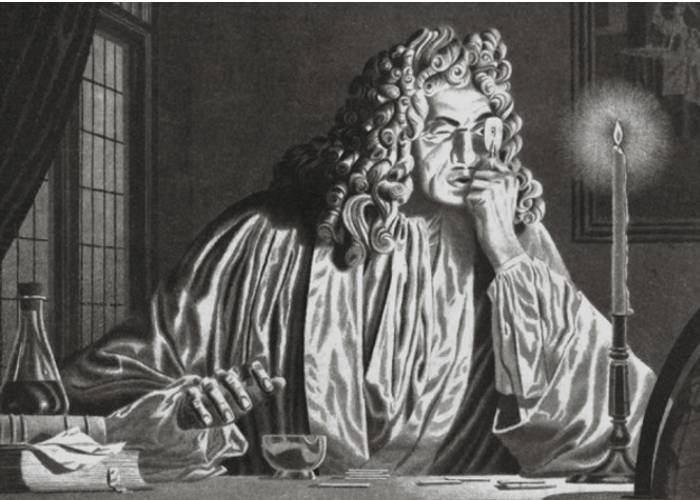

Her master, Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, has just discovered another wondrous animalcule in a scraping taken from his own mouth. The being was butternut shaped, with two rows of numerous abdominal leglets and three long antennae on what looked like a head. He observed it through the lens for so long that his eyes started aching. Another tiny being and indeed very voracious – he saw how it devoured a thin worm that happened to be near it.

There were other animalcules in that scraping from his mouth, lots of them – but he already knew them well. All those living creatures shaped like little eels, and drums, and balls with tails, and shoes – he had already observed them and described them in his detailed letters to the Royal Society.

Next morning, when he was sipping his coffee, he had a hunch. Having set a cup of coffee aside, he instantly collected the material directly from his tongue and put the smear under the glass. He could not believe his eyes. There was not a single tiny organism visible. Hot coffee must have eliminated all those fantastical forms altogether.

It was almost noon when he finally tore himself from the glass.

A man was walking through Delft – tall, gaunt, with a large, crooked nose and bulging eyes looking cheerfully and mischievously upon the city. Having reached Leeuwenhoek’s house, he rang up and said to Griet who opened the door, “Balthasar Bekker for Mynheer Leeuwenhoek. He is expecting me.”

Leeuwenhoek was in his studio sitting at his desk covered with books and papers, writing something.

“Ah, Mynheer Bekker!” he said a bit petulantly putting down the quill and rising from his chair.

“Good afternoon, Mynheer Leeuwenhoek,” said the guest. “It is such a pleasure to meet you after hearing so much about you and your marvellous discoveries.”

Leeuwenhoek nodded and said, “You have come a long way from Amsterdam. Please have a seat. Griet, bring us some wine please.”

“Mynheer Leeuwenhoek,” said the guest after he drank good health to the master of the house. “As I have mentioned in my letter, like so many in our country and beyond, I have heard a lot about your magical lenses. Please forgive me for tearing you away from your scientific studies, but there is a long-standing issue which I believe only you can help resolve.”

“I am not a scientist, Mynheer Bekker,” said Leeuwenhoek. “The townsfolk say I am just a merchant. But indeed I’m curious to know what has brought our acclaimed theologist to this house.”

Bekker, flattered, smiled. He reached inside his pocket and put something on the desk. It was a small wooden box.

“I am seeking your help in resolving one of the most important theological challenges, Mynheer Leeuwenhoek,” he said solemnly. “This issue was first mentioned by the English as purely scholastic. It does not seem so to me. I believe we can still find a scientific solution to this conundrum.”

Bekker opened the box. It was lined with black velvet. There was a needle inside.

“I washed this needle in Holy Water and then prayed over it for three days summoning angelic forces,” he said. “I am hopeful that they will help us to find an answer to the question which torments me. This question is how many angels can stand on the point of a needle. This needle.”

There was a pause, and then Leeuwenhoek asked, “Is this your most important theological challenge, Mynheer Bekker?”

“Well,” said Bekker, “I should think so, although I am also wondering if there are any angels on the needle’s head at all.”

Leeuwenhoek looked at him gravely.

“Do you believe that your prayers made the angels descend on the needle?” he asked.

“You are a scientist, Mynheer Leeuwenhoek,” said Bekker, wagging a finger at Leeuwenhoek humorously. “Only a man of science could ask this question. May I ask if you believe in God?”

There was another pause.

“Mynheer Bekker,” said Leeuwenhoek at last, “you said that you have come here to seek scientific advice. Now you are enquiring about my faith. Do I need to pray for three days before examining this needle through my lens? Or wash the lens in Holy Water? Perhaps this way the angels would become more visible?”

“No, no, Mynheer Leeuwenhoek,” laughed Bekker. “I did not mean to offend you. I just wanted to put this in the right context. If you do not believe in God or angels, it would be quite difficult for you to get a sight of them on this object.”

“I know what angels look like,” said Leeuwenhoek dryly. “Halos, wings and all. I am pretty sure I will recognize them. The question is, what makes you think that we will be able to see them through my lenses?”

“This is exactly what I wish to find out,” said Bekker. “Call this an experiment.”

“Something tells me that the English were right,” grumbled Leeuwenhoek. “This is not even worth a scholarly debate.” He opened a cabinet and took out one of his lens holders. “I am not going to waste any more of your time and will resolve your long-standing theological challenge right here,” he said.|

“By all means!” said Bekker with a courteous smile.

Through the lens the needle looked enormous like a bowsprit, and its point, blunt and flattened, was lined with deep wrinkles like a whale’s back.

“Ah,” said Leeuwenhoek. “There is enough room for a whole army here. If your angels were ants, a few hundred of them would fit into it.”

“Are there angels there?” cried Bekker ecstatically.

But Leeuwenhoek just laughed in amusement.

“Look at this thing,” he said. “Just look at it, Bekker. I have never thought that a needle would look like an old log.”

Bekker took the device and peered into the lens cautiously.

“Good Lord!” he gasped. “Is this really the needle?”

“Yes,” said Leeuwenhoek. “So, Mynheer Bekker, can you see the angels?”

“Not a single one,” said Bekker with a sigh, returning the lens.

“So much for this most pressing theological issue,” said Leeuwenhoek. “But let me have another look to be sure.”

He started looking into the glass and this time he did this for quite a long time.

“What?” said Bekker with renewed hope. “What’s there, Mynheer Leeuwenhoek?”

“I don’t know”, said Leeuwenhoek slowly, still examining the needle. “I think I should have a better look through a new lens. The one I was going to grind.”

“Do you think you see something?”

Leeuwenhoek put the lens on the desk.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Maybe. Are you staying in Delft for a while?”

“There is always business to do in Delft,” said Bekker. “How long will it take for you to make a new lens?”

“I’ll try to get it done as soon as I can. Please call to me the day after tomorrow. We’ll take a look together.”

“This is so very kind of you, sir,” said Bekker, radiant with joy and hope. At the door he stopped and asked, “What have you seen there?”

But Leeuwenhoek just shrugged.

When Bekker was gone, he grabbed the lens and started looking again.

After a while, deep in thought, he put the lens aside. “What have you seen?” asked Bekker. He did not respond because, in all truth, he did not know.

“Griet!” he called out. “Griet!”

The old maid came in instantly as if she was listening at the keyhole. She looked excited.

“More wine, sir?” she asked.

“Griet,” said her master, “I wanted to ask you a question.”

“Yes, sir?”

“How many angels do you think can sit on a needle’s head?”

She was gawping at him, wide-eyed.

“Griet?” he said gently. “I know, this is difficult. Just guess.”

“Eh?” she said.

“I’ve just asked you a question.”

“Heaven knows, sir! Why are you asking me that?”

“Because I am curious. Just answer the question.”

She was gawking at him.

“Not loads of them if they are fat,” she said finally and started laughing.

He was looking at her silently. Griet roared with laughter, her face turned red. At last she stopped and coughed, gurgling with her throat.

“Silly woman,” said Leeuwenhoek quietly. “Get out!”

She stared at him, her eyes popping out.

“Get out!” he yelled.

Griet shrieked in horror and ran out of the room.

That afternoon, Leeuwenhoek began grinding the lens. This process was always long and laborious. He started grinding the piece of glass into a cylindrical shape but then suddenly put it aside. It was raining hard outside, the rain drumming on the window. He stood there, looking out of the wet window, unable to resume work.

He thought about angels. God’s messengers as they were, would not they come to the needle’s head only if God wanted them to? Ergo, would God only want them to descend onto the needle if He wanted them to be visible for some reason? What is a message they have to convey? And who is that pure soul that would be allowed to see the immortal spirits?

He took the needle. Holy Water! What nonsense!

The lens was before him, the window into the other world. He took the tiny piece of glass and put it to the rotating disc attached to his pedal lathe. After grinding it a bit he cast another cautious look at the needle through the newly ground lens.

There was nothing visible in the deep wrinkles on the needle’s head.

That night he had a dream – a giant eye was looking at him from above. His wife woke up from his deep groan.

Next morning he got down to work with a new zest. Fear has evaporated, as if the night dream had swept it away. Leeuwenhoek was grinding and polishing the lens until the early afternoon hours. Finally he got a feeling that the lens was ready. Never before has he worked on a lens with such fervour. He stood there hesitating for a while and then peered at the needle through the new lens.

He stood there gazing into the lens until his eyes welled with tears from strain.

Bekker turned up next morning and found Leeuwenhoek deep in some dismal thoughts.

“Sit down, Mynheer Bekker,” he said, not looking at the guest.

“Have you ground your new lens, Mynheer Leeuwenhoek?” asked Bekker, tingling with excitement.

“Yes.”

“Have you… have you seen anything through it?”

After a pause, Leeuwenhoek said, “Nothing resembling angels. You may want to have a look yourself. Who knows, perhaps you will see something.”

Bekker grabbed the device and pressed it against his eye. For a few moments, he was silent, only his breath was getting louder. Finally, disgruntled, he lowered his hand with the device.

“I… I cannot see anything,” he uttered.

“I am sorry, Mynheer Bekker,” said Leeuwenhoek. “Would you like some wi…”

“I can only see some repulsive creature,” said Bekker, pressing the device against his eye again. “It looks like… a slipper! It is exactly like my grandma’s slipper! But it’s moving! What have you done to my needle, Mynheer Leeuwenhoek? What is this thing there on the needle’s point?”

Leeuwenhoek laughed.

“Oh, never mind. Those are neither angels, nor demons. It is just one of those wonderful animalcules I have discovered,” he said. “They seem to be everywhere, in every drop of water.”

“But not in Holy Water!” cried Bekker. “They can’t be in this sanctified substance, these god-awful things! What are they doing on my needle?”

“As I have said, Mynheer Bekker,” said Leeuwenhoek, “they are everywhere. Even in rainwater. Why can’t they be in Holy Water? I believe they are living beings just like other animals living on this earth, only very tiny ones.”

Bekker looked at him narrow-eyed.

“Mynheer Leeuwenhoek,” he said slowly, “tell me frankly – is this the same needle? The one I gave you, the one that was blessed?”

“Let me show you something,” said Leeuwenhoek. “If you wait a moment, I will show you the creatures that are exactly the same. I’ll simply take a sample from that barrel with rainwater, and you will see that they are there, right in the water fallen from the sky. Or, if you permit, I’ll collect a swab from your tongue…”

Bekker sprang to his feet.

“This is outrageous,” he said. “I do not know what you are playing at. Is this some sort of a magic lantern? Are you going to show me the demons inhabiting my mouth?”

“Not exactly demons…”

“Enough of it!’ said Bekker. “I am leaving, Mynheer Leeuwenhoek. No one can play tricks on me.”

At the door he stopped and slurred over his shoulder, “Fancy finding not a serious scientist but a wag in this house!”

Leeuwenhoek remained seated. Slowly he took the needle and peered at it through the lens.

There was nothing on it.

Griet waited until the master left, apparently heading out for a walk, and then entered his studio. She did try to listen in when the master was speaking with the guest but could only pick up some words. What she grasped from their conversation clearly was that they were looking at a needle through one of those devices of her master’s. And, having rushed into the studio, she immediately saw the needle and the lens holder – both were on the master’s desk.

Quickly she grabbed the needle, pressed the lens against her eye and stared at the thing. Immediately she cried and dropped the device.

Later that afternoon, Griet came down to the kitchen. Bea was busy chopping meat for dinner. With a strange smile Griet said, “I’ve got something to tell you.”

“What’s that?” said Bea, her knife clattering against the chopping board.

“Our master’s got a needle,” said Griet. “Just a regular needle – but if you look at its point through one of his things, like I did, you’d see angels!”

Bea stopped chopping meat and stared at Griet.

“Like those in church? With wings?” she said.

“Yeah,” said Griet.

“They must be tiny if they can sit on a needle’s head,” said Bea.

“They are!” said Griet. “And there are dozens of them. Like small ants.”

“I wonder,” said Bea, resuming her chopping job, “how did he do that? Putting angels on a needle! God knows where he got so many of them!”

“And I wonder,” said Griet, “why did he put them on the needle? Do you know what they were doing?”

“No, what?” asked Bea.

“They were dancing!” said Griet.

“All of them?” asked Bea.

“Yes, all forty-seven of them,” said Griet. “He may have put the poor things onto the needle – but why did he force them to dance?”

And she added in astonishment, “Crazy man! Poor old looney!”