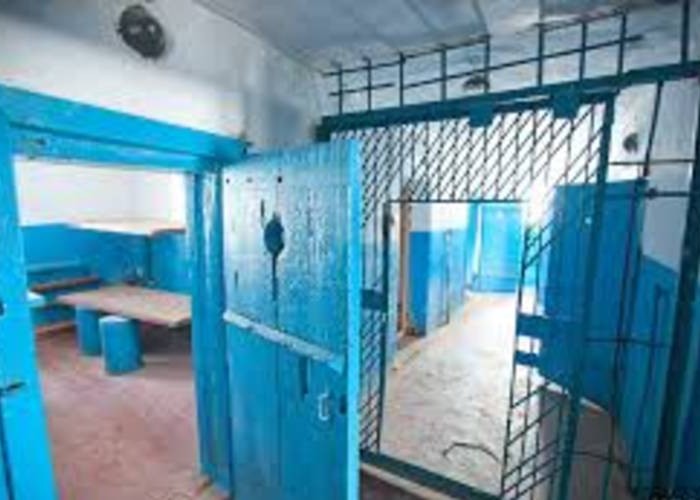

The poet was dying. His hands, swollen from hunger, lay still on his chest, pale, bloodless fingers with filthy, overgrown nails. He no longer tucked them under his shirt for warmth—there was too little left there. His mittens had long since been stolen. All it took was the nerve, and they’d steal them in broad daylight. A dim electric sun, clogged with flies and locked behind a circular grate, hung high on the ceiling. The light fell across the poet’s legs—he lay in the darkness, tucked into the lower tier of the wooden bunks, like a man in a coffin. His fingers would twitch now and then, snapping like castanets, feeling for a button, a hole in his jacket, brushing off some lint, then freezing again. He had been dying for so long that he no longer recognized it.

Now and then, a clear and simple thought would cut through the fog in his mind—his bread had been stolen, the loaf he had tucked under his head. The realization burned in him, an unbearable rage, and he was ready to argue, to fight, to demand answers. But he lacked the strength, and the thought of bread faded. His mind drifted instead to other things—the sea, how they were supposed to take everyone across the ocean, and for some reason, the steamboat was late. He was glad to still be here.

And just as easily and fleetingly, his mind wandered to the large birthmark on the face of the barracks guard. For most of the day, his thoughts circled around the small, immediate moments of camp life. There were no visions of childhood or youth, no memories of success. He had spent his whole life rushing somewhere. Now, it was a relief not to hurry. To think slowly.

He thought about the strange uniformity of a dying man’s movements, something doctors had written about long before the poets. The death mask—Hippocrates’ face—is familiar to every medical student. That repetition, those final gestures, had given Freud reason for his boldest hypotheses. Science thrives on repetition, on the search for patterns. But what is unique in death—this is for the poet to discover.

It was comforting to know that he could still think. Starvation’s nausea had become a constant companion, but it didn’t bother him anymore. Everything felt equal now—Hippocrates, the guard with the birthmark, his own filthy nails.

Life would enter him, then leave again, and he would be dying. But life returned. His eyes opened; thoughts began to form. Only desire was absent. He had lived long enough in a world where life was often brought back—by artificial respiration, by glucose, by camphor, caffeine. The dead returned to life often enough. Why not? He believed in immortality, in true human immortality. There was no biological reason, he thought, why a person shouldn’t live forever. Old age was just a curable disease, and if not for this one tragic misunderstanding, he could have lived forever. Or at least until he grew tired of it.

But he wasn’t tired of life. Not even now, in this transit barrack—the “transitka,” as the prisoners called it, almost affectionately. It was the threshold of terror, but not terror itself. In fact, the spirit of freedom still lingered here, and everyone could feel it. Ahead was the camp, behind them the prison. This was a world in transit, and the poet understood that.

There was another path to immortality—Tyutchev’s:

“Blessed is he who visited this world

In its dying moments.”

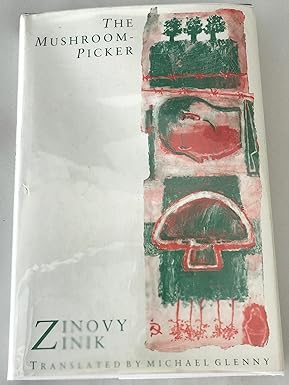

Even if, as it seemed, he hadn’t been granted physical immortality, at least there was artistic immortality. They called him the first poet of the twentieth century, and he believed it. He believed in the immortality of his verses. He had no disciples—what poet could endure them? He had written mediocre prose, some articles, but only in poetry had he found something truly new to offer, something important. His entire past life was a story, a book, a fairytale, a dream—only the present day was his true reality.

These thoughts didn’t stem from argument, but surfaced quietly, somewhere deep within him, lacking any trace of passion. Apathy had consumed him long ago. All this, he realized, was nonsense— “mouse’s errands” compared to the overwhelming weight of life. He was surprised at himself—how could he think this way about poetry when he knew, better than anyone, that it was all over?

Who needed him here? What was he worth? Why did any of this need understanding? And yet, he waited—and he understood.

When life flickered back into him—when his half-closed eyes suddenly began to see again, when his fingers twitched—thoughts returned too, thoughts he hadn’t expected to be his last.

Life re-entered him like a domineering mistress. He hadn’t invited it, but it came in all the same, into his body, into his mind—into him as poetry, as inspiration. For the first time, the meaning of the word “inspiration” became clear to him. Poetry was the force that had kept him alive. Without question. He didn’t live for poetry; he lived as poetry.

It was so clear to him now, as death loomed, that inspiration—breathing in—was life itself. He was granted the understanding that life was nothing but inspiration.

And he rejoiced that he had been allowed to understand this, at last.

Everything in the world was equal to poetry: work, the trampling of horses, home, birds, cliffs, love—all of life had always flowed effortlessly into his verses, finding its place there. And so it should be, for poetry was the Word.

The stanzas came to him now in waves, even though he hadn’t written anything down for a long time, nor did he have the strength to record them. Still, they came in a predetermined, unrepeatable rhythm. Rhyme became a divining rod, searching instinctively through words and meanings. Every word was part of the world, echoing with rhyme, and the whole world seemed to carry it forward at the speed of a machine. Everything cried out: Choose me. No, me. There was no need to search, only to reject. It was as if there were two of him: one who set the record spinning, faster and faster, and the other who, from time to time, lifted the needle.

And realizing that he was two people, the poet knew that he was still composing real poetry. So, what if it wasn’t written down? Writing or publishing was vanity—vanity beyond vanity. The best poetry, the highest, was that which was never recorded, that which was created and disappeared without a trace. Only the creative bliss remained, a sign that poetry had existed, that beauty had been made. Was he wrong? Wasn’t the joy of creation unmistakable?

He remembered how poor, how poetically helpless Blok’s last poems were, and how Blok, it seemed, didn’t realize this…

The poet forced himself to stop. It was easier to do here than it would have been in Leningrad or Moscow.

Now he realized that he hadn’t thought of anything for a long time… life was slipping away from him again.

For several hours, he lay still. Then, not far from him, something caught his eye—like a rifle target or a geological map. He squinted, trying to make sense of it. The map had no labels, and for a while, he tried in vain to understand what it depicted. It took him some time to realize that it was his own fingers. The faint, brownish traces of a smoked-down mahorka cigarette stained his fingertips—his fingerprints were shaded like the relief of a mountain range. The pattern was the same on all ten fingers—concentric circles, like the cut of a tree.

He remembered a Chinese man who had once stopped him on the street as a boy. The man came out of the laundry in the basement of their house and grabbed his hands, turning his palms upward. In his native language, the man had exclaimed something loudly and excitedly. It seemed to the poet that the man had declared him lucky—a bearer of good omens. The poet had recalled this moment many times throughout his life, especially when his first collection of poetry was published. Now, he remembered it without irony, without bitterness—just as it was.

The most important thing was that he hadn’t died yet.

What did it even mean to die a “poet’s death”? There should be something childlike, naive about it. Or perhaps something dramatic, theatrical—like Esenin or Mayakovsky.

An actor’s death is simple. But a poet’s?

He felt as if he were on the verge of understanding something important about what awaited him. He had learned so much on his way to this point. And he felt a quiet joy in his own weakness, a hope that death was near.

He remembered an argument from long ago in prison—what was worse: camp or prison? No one knew the answer, and all the points were speculative. But he remembered the grin of the man who had been transferred from camp to prison. That grin stayed with him, so much so that it now frightened him to recall it.

How easy it would be to deceive them, the ones who had put him here, if he died now. Ten whole years. A few years ago, during his exile, he had known that his name was on special lists—forever. Forever? The meaning of words had shifted; they no longer meant what they once did.

Again, he felt a surge of strength—like a tide rising within him, only to recede once more. But tides never stay away for good.

He would recover.

Suddenly, he wanted to eat, but he didn’t have the strength to move. Slowly, painstakingly, he remembered that he had given his soup to a neighbor. All he had consumed that day was a cup of hot water. Apart from the bread, of course. But that had been distributed long ago. And yesterday’s bread had been stolen. Someone still had the strength to steal.

So, he lay there, his mind light and empty until morning came. The electric light in the barracks grew slightly yellower, and the bread was brought in on large plywood trays, just as it always was.

But he no longer stirred. He no longer watched for a crust, no longer wept when someone else received more, no longer rushed to cram a morsel into his mouth with trembling fingers, savoring the taste, the smell, letting it melt slowly. He no longer felt the miracle—the small miracles that happened here—when the bread melted in his mouth, though his jaws barely moved, and his teeth were unable to chew.

When they placed his daily ration in his hands, his bloodless fingers grabbed the bread, and he pressed it to his mouth. He bit into the bread with his scurvy-ridden teeth; his gums bled, his teeth wobbled, but he felt no pain. With all his strength, he pressed the bread to his mouth, shoved it in, sucking, tearing, and gnawing at it.

His neighbors stopped him.

“Save it. Eat it later. You’ll need it later.”

And the poet understood. He opened his eyes wide, refusing to let go of the bloodied bread in his dirty, ashen fingers.

“Later? When?” he said clearly, distinctly. And he closed his eyes.

By the evening, he was dead.

But his death was recorded two days later—his inventive neighbors managed to collect his bread for two days by having the dead man raise his hand like a puppet. It turns out, he died earlier than the official date of death—a detail not without significance for his future biographers.

1958

_________________

Translated by Naza Semoniff