FROM A DIARY OF THOSE YEARS (excerpts)

Before I even wаke up, I count days. Five in August, thirty in September… I stop doing this arithmetic at the end of the second month. Now I count weeks. It seems that this is how they count children – unborn or newborn. In four days is the anniversary: exactly three months since we’ve been in Chicago. I’m trying to understand: is this a lot or not? (November, 1996).

*

Pain pierces me, relentlessly. It comes back, like pains of a woman in labor, gnawing at me, never pausing. Sometimes I want to immerse myself in it, to adjust to it, to numb myself. I can’t. Of course, it does not leave me at night, only in my sleep I feel it as if from afar. A month of my farewell to Lithuania and a month and a half in Chicago passes with this pain. In Vilnius, the ambulance doctors try to help me to no avail. Finally, in the U.S., the pain is overcome by the usual pills I buy at Walgreens. The sages say that the Almighty warns us of something through the language of pain.

*

There’s one common measure of emigration: the English language. Our life with it and in it. My English teacher is Polish. He came to America as a child, now he is thirty-seven. How do I know that? He said so himself. He also told me about his wife, who is five years younger than him; who is a doctor and earns three times as much as M., and is a source of pride for him;

about his mistresses, his girlfriends he had before his wife, though the wife had been his girlfriend for several years;

about his wife’s tastes and dislikes—most of all, she hates bad breath and likes “making love,”

about the reasons for their quarrels. Here’s one that often comes up: when making a pee-pee in the toilet (the teacher pronounces it in Russian), M. lifts the toilet lid so as not to splash. Coming back from work, his wife hurriedly sits down directly on the cold earthenware surface, jumping up frightened, screaming….

Sometimes I think: does M. have a wife? Maybe it’s all just a trick—a pedagogical trick to intensify the perception of his beautiful English speech.

He sits in the middle of the room with his legs stretched out. He can, in full view of the whole group, without interrupting the story, tie his shoe laces or scratch any part of his seal-like body. He speaks with a discreet glance at his watch. I’ve checked many times: he doesn’t miss a single minute—he cuts off the conversation almost in the middle of a word, to say at exactly three o’clock:

“Break. Pereriv.”

No, he’s not a hack. He’s a virtuoso at his craft. And like any master of his craft, he enjoys it when I tell him so. “Is it true? Is it true?” he interjects.

He was especially virtuosic at the beginning of the course. Singing songs, playing a part of some animal or different types of Americans….. M. is also quite a virtuoso at hiding the fact that he knows Russian perfectly well.

There are usually ten or twelve people in the class. The tables are arranged in a semicircle. No textbooks. No grammar. Every day M. gives us xeroxed sheets of paper. It’s material for thinking. You have to imagine yourself as a banker who has to decide whether to give someone a loan. Or a member of a commission deciding which school programs to cut and which to keep. Or… There’s a sheet of paper with the raw data on it. “We’ll discuss it tomorrow.”

Exactly quarter to five M. closes his mouth and leaves the classroom. On a cold day he throws a brightly colored sweater over his shoulders. He doesn’t have far to go—just to the parking lot where his white Toyota Camry is parked.

I’ll never know where he is off to. (January, 1997)

*

“In-between”. This is a title of an article by Yuri Tynyanov on Russian poetry of the early nineteen twenties. “In-between” — can’t find a better definition for emigration. An emigrant is a person who is in-between.

*

Emigration or immigration? An unnecessary dispute. Any encyclopedia will provide a definition: an emigrant is someone who leaves his homeland; an immigrant is a person who has already arrived in another country. Why am I particularly interested in emigrants? Their fates invariably carry tragedy (or at least drama). They left Russia (or another former Soviet state) and never made it to America. They are “in between.” Forever?

*

Emigrants themselves, of course, are concerned with justifying their emigration. These justifications take different shape in different years. Now, as a rule, they are oriented not at the “top” but at the “bottom” of a person. Nowadays, not only will no one say, no one will even think “We are not exiles, we are messengers.” More convincing to many are the words written by a Chicago journalist, with simple-minded cynicism, in the early 2000s: Take a piece of fresh Borodino bread, spread it with Vologda butter, put a Doctor’s sausage* on top… You haven’t forgotten your nostalgia for your homeland yet? (Aug. 2005)

*

George Gurdjieff, that great “seeker of truth,” had no doubt: man is a machine. A creature living mechanically and immersed in the stupefaction of sleep. Gurdjieff’s experiments, which shocked and attracted the intellectuals of Europe, had one goal: to awaken man from the “dream of reality”.

Emigration, of course, awakens our sleeping consciousness. Let me quote Dina Rubina, who did not exaggerate when she said that emigration is “a harakiri, your intestines are slapped on the asphalt.”

Yet emigration itself is also a dream.

*

Scientists have a cheerful way of reasoning: “Moving to another place improves memory. An average person moves about 5 times in their lifetime. Studies have shown that moving is a difficult ordeal (harder than divorce). However, scientists from the University of New Hampshire have found that it has at least one plus. It helps us remember things that happen to us.” (August 2016 news reports)

*

…As if arguing against these arguments of science, a strange couple walks leisurely toward me along Devon Avenue in Chicago. She is tall, gaunt, like an autumn tree with leaves falling off. He is chubby, unnaturally red-cheeked, barely reaching her shoulder. When they notice me from a distance, they smile. Last fall in Hot Springs (a mountain resort in the south of the US) we often walked through an old park. Yuri, who once, like me, taught at a university (his lectures drew fans from other cities), was now shy and silent. The longest sentence he uttered at the beginning of our friendship was: “You can call me by my first name, because we meet in the West where people are not used to patrnonymics, right?”.

I did not realize that he had been stricken with Alzheimer’s. With his wife’s help, he skillfully conceales it. Fira answers my questions about literature departments in Moldova. And Yuri nodded, sadly and affectionately.

Once, when he dozed off on a bench, intoxicated by the harsh mountain air, Fira whispered their story. Alzheimer’s had attacked her husband suddenly and was winning without much ceremony. Thank God we’re already here in Chicago, where the future isn’t so scary, she said. Thank God he hasn’t gotten violent, even though the doctor warned him about it. Thank God Yurochka hasn’t completely lost his mind. And he even came up with an explanation for his memorylessness: “Most writers, bringing back the past, revive it, savor their memories. But I don’t want to remember. My past is saturated with longing.”

*

“Emigration is a disease,” I write in my notebook. And I forget to think about the main thing: how long does this illness last? Of course, there are several options. Reading a book by Fritz Perls, founder of Gestalt therapy, I come across a reminder: illness is an unfinished situation; it “may end in recovery, death, or a reorganization of the organism.”

*

Russian-speaking communities in American cities are becoming shelters for the elderly. Mass emigration from Russia has long since ended. The heated debates in newspapers and on the radio about how many KGB agents came with us; who wrote And Quiet Flows the Don; who was Georgy Zhukov — the savior of Russia or a “butcher” who callously sent soldiers to certain death — have subsided. Disputants who, just yesterday, were intolerant of each other, peacefully meet today at an urologist’s office, on a cruise to the Bahamas or in a “kindergarten” for the elderly. (Dec. 2017)

*

Human destinies, in emigration barely immersed in everyday life, are laid bare. Emigration emphasizes their brokenness, their strangeness, often their enigma.

*

On the same Devon Avenue that for many years sheltered Russian emigration in Chicago, leaning against the wall of a grocery store, stands a man whose appearance repels and, at the same time, attracts passers-by. He says of himself: I work as a beggar. It is not easy to decide how old he is: between forty and sixty. In any case, I couldn’t see any gray in his blue, wispy beard. He has a prosthetic leg in place of his left leg, which is not hidden, as it happens, by his pants. His eyes are the most remarkable thing about his face: they are large, or seem so, because the man looks at you firmly and intently, almost without averting his gaze.

We haven’t said anything to each other in years. But I know his name: Ilyusha. A soft, warm name, it seems to have been unsuccessfully rented by him. Many American beggars hold out a jar or a box for alms, with a few dollars; coins jingle, as though to rebuke passers-by. But this legless man only looks at you, through you, and you yourself, without invitation, take out your purse.

One winter day, I met Ilyusha in a doctor’s waiting room. He was on his way out of the door, but he stopped when he recognized me. He asked me confidently: “Can you give me a ride to work?” It’s only a five-minute ride, but of course it’s hard for Ilyusha to walk: the scalding winter wind in Chicago knocks even healthy people off their feet. He sat silently next to me in the car, looking in a window — as if for the first time, he looked at the street where he spent decades of his life. Of course, Ilyusha was not at all embarrassed by the smell emanating from his gray jacket, which he wore in any weather.

I was told that he had once graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy at Moscow State University. Philosophy Department? I asked in my mind, with a chuckle. And immediately, I remembered sentimental novels of the century before last. I have no doubt that this was one of the myths of emigration, which was in love with myth-making. But then T., who knows everyone and everything, swore that he had actually seen Ilyusha’s MSU diploma.

What brought him to Chicago and made him choose the ancient profession? I often wanted to talk to Ilyusha. But every time, I was stopped by his rigid look. It was like a door bolt, not letting me in.

*

Anatoly Simonovich Liberman, a famous linguist, professor at the University of Minnesota, was talking on the phone:

“Our past Soviet life has averaged us out, to a surprizing degree. Our whole generation, we were like peas from a pod. To quote my wife, we all look alike, like a fireman’s gray pants. When we meet, we recognize each other. The same quotes, thoughts, memories.”

In fact, I recognize my kind everywhere. I recognize, unmistakably, the fear that most of us try to hide. It is the only baggage of an emigrant that, alas, cannot be lost or left in a locker.

Fear is one of the main themes of my book “Long Conversations in Expectation of a Happy Death. From the Diaries of These Years” (1996). For five years, I have been listening to the confession of the dying Lithuanian-Jewish playwright and critic Y. For five years, “at the very edge of life,” we have been trying to reconstruct his many fears, together. Or at least, to make sense of them. By the way, his fears ended only with his death.

*

The day before yesterday, after work, I was walking in a park near my house. I was talking on my cell phone. Suddenly I heard a voice with a strong accent: “How nice to hear beautiful Russian speech…” A middle-aged woman.

I asked her: “Are you from Russia?”

“No, I’m from Latvia. But I’ve been here for almost thirty years. And I miss the Russian language…”

“?!”

“I like to learn languages. I know five, and I’m learning the sixth one, Japanese…. I’m going to Japan for an internship.” She told me more about herself. The details were not important, even her profession was not too clear (something related to alternative medicine)…. We parted after a few minutes. She offered to exchange phone numbers.

Soon enough she called me: “I have a favor to ask you. If we meet by chance in some public place, pretend that you don’t know me…” She repeated this several times. I tried to calm her down. I gave her my word not to acknowledge her. And I didn’t ask her anything. I didn’t want to go into the depths of her fears.

*

Interviews with those who suffer from insomnia in emigration: they wake up at three in the morning and do not sleep until morning. They say that at that time the heavens want to convey to them something important.

Another typical response: “I like to lie in the dark with my eyes closed. I try to see myself from the outside. Over the years, I have come to regard myself as an outsider. I ask: “Is there any meaning in this person’s life? And is it possible to change his fate?”

*

For over twenty years I have been editing a Russian-language monthly in Chicago. There are many publications of this type in America: something between a newspaper and a magazine. A book could be written about “how I worked as an editor”. Too bad such a book was written a long time ago. (See Mark Twain’s notes or Dina Rubina’s novels).

*

In the new edition of Yuri Olesha’s diary, which used to be called “Not a Day Without a Line,” and now, re-composed and supplemented, is published under the title The Book of Farewell, I read: “Human fate, the lonely fate of man (…) has been the most necessary theme, for generations. All the world’s literary works are built on it. Remarque’s book is the best that was written about it in recent years. It echoes another book of lonely fate — Hamsun’s “Hunger”. Now I turn to my own fate and see: loneliness. Let a book about loneliness emerge in the era of the greatest movement of the masses.”

Loneliness, like vulgarity, is a symbol of emigration. (Aug., 2000)

*

I don’t come to the editorial office at the same time: I come at nine, sometimes at ten or eleven in the morning. I have nowhere to hurry: I can work from home. And Boris sits in the reception room, waiting. I am ashamed; every time I apologize to him. Although it’s not my fault: in America, you’re supposed to arrange a meeting in advance, and here, unlike in Russia, no one comes by just “for a visit.”

“What’s new?” I say. And I know the answer in advance: “I’m sorry, I just miss socializing.” Boris is not a bad poet. I ask him to read old poems or to tell me about Tajikistan, where he used to live and where he was published. What else can I do for him?

*

Old emigrants (those who are eighty and older) are typical Soviet people. Very rare are their epiphanies, like that of Boris Z., who concludes his letter with a sigh: “The Communist idea is wonderful! We only have to make sure that it never comes to life.”

*

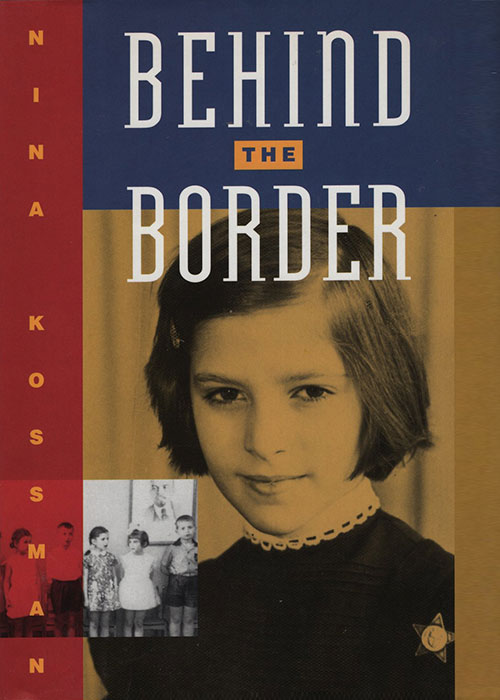

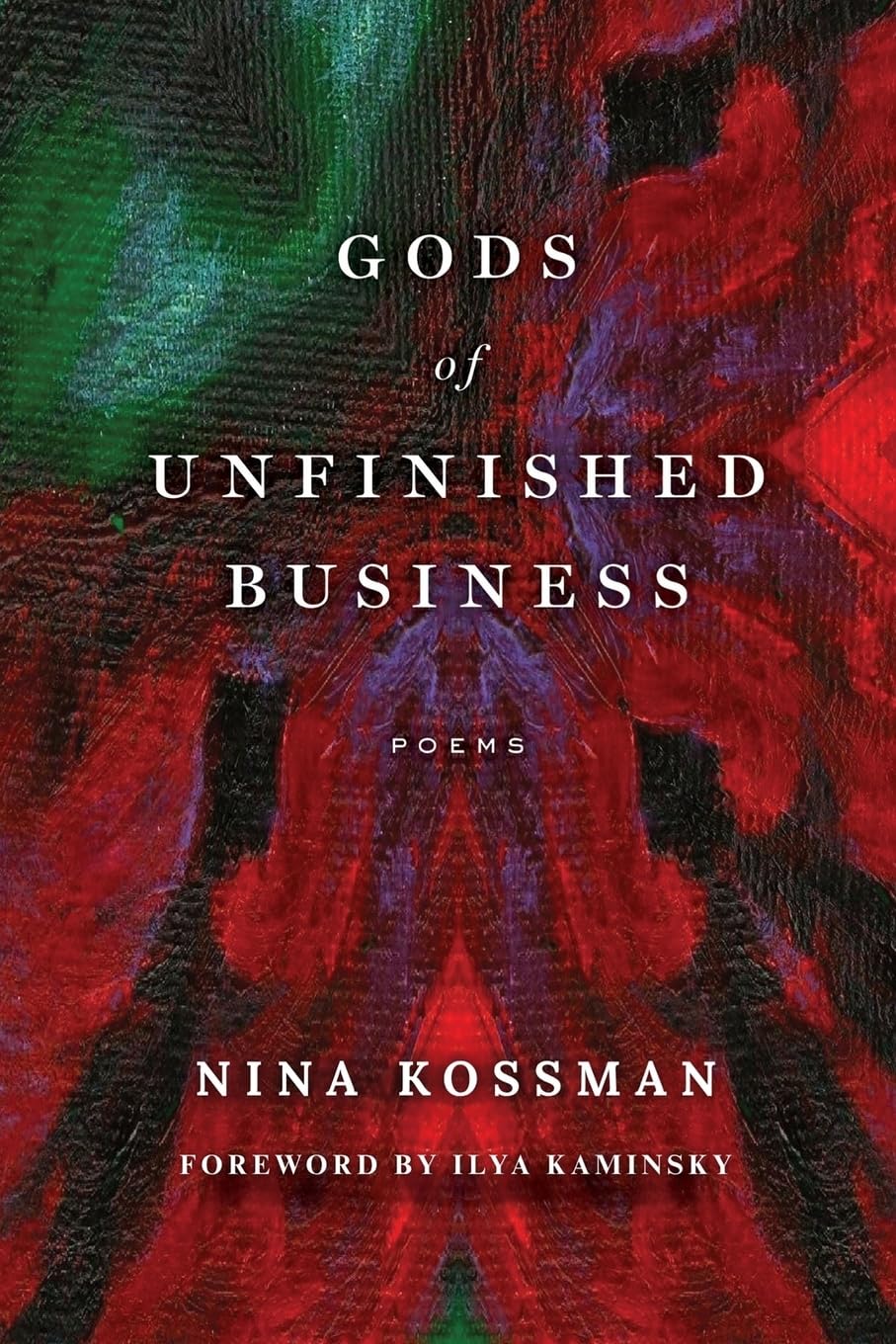

Books are pouring into the editorial office. I am perplexed: why do so many people, having just emigrated, want to become writers? They immediately “take up the pen”, i.e. master the computer.

A person here loses his profession (often, because no one needs it here). Meanwhile, deep inside, he has an unmistakable feeling that he has a unique experience of life, the world must know of it.

Alas, writing books is a profession. 99.9 percent of books published in emigration are colorless products of graphomaniacs.

*

Emigration as an idea and as reality are two different things.

As an idea, emigration is wonderful: it reveals to the writer the essence of many things — in particular, his true vocation.

Alas, the reality of emigration is something else. It’s crude. Cynical. Harsh. Emphasizing the uselessness of creativity.

*

A Russian literary man, of course, is one of the emigrants. It doesn’t matter whether he knows English. He thinks and writes in Russian.

He is in-between. Isn’t that why many literary men in emigration are filled with anxiety and irritation? At whom are they irritated? At Russia, where they were once unappreciated and where they are still ignored by literary critics. At antisemites in that same Russia they left (although state anti-Semitism has long since stopped being an issue there). At American bureaucrats. And at the end of the day, at themselves. At their own fate. Sooner or later they realize the senselessness of this feeling. Do they accept it or do they only pretend to?

The essence of this condition has been defined by F. Perls: anxiety is a gap, a tension between “now” and “then”.

*

That talented poet Alla T. Her articles about émigré writers are saturated with anger. A boomerang? How could she not realize it? Of course she did. But too late. When she was mortally ill, she reached out to people she had recently poured piles of mud on. Asked for forgiveness.

*

“Hello, bro, it’s very hard to write!” the Serapion Brothers used to say to each other. In emigration, this greeting sounds mocking: who can even hear the lonely voice of an author trying to say something in a foreign language?

Nevertheless, emigration is the best place for creativity. If, of course, one has managed to curb one’s irrepressible vanity.

*

In November 2013, Roman Vershgub, an old doctor and emigrant from Ukraine, passed away in Chicago. Many people take a secret with them when they die. It always seemed to me that it does not have to be solved at all — a person has the right to under-tell the story of his or her life. And yet this was a special case.

The first time I heard of Roman Vershgub’s writing was from Efim Petrovich Chepovetsky, a famous children’s poet, in his last years of life in Chicago. “Beautiful prose,” exclaimed H.P. “But the snag is that Roman doesn’t want to publish it.”

He typed his stories on a typewriter: two or three copies. And he’d let two or three people read them. When we met, Roman honored me with letting me read them. What struck me immediately about his stories? They were clearly written by a professional.

I made the same mistake as the others. I asked: would you like me to recommend your work to one of the emigrant magazines I have connections with? And I received the same categorical refusal.

He was already hopelessly ill. He knew it. And he gave in to the entreaties of his friends: he began to read his works in Chepovetsky’s literary studio. However, he spoke against the need for unnecessary publications even more firmly.

Maya, Roman’s widow, went against his will. It is not for me to reproach her. In the old days legends about Maya, a homeopathic doctor, were common in Kyiv. And now, a few decades later, she was practicing oriental gymnastics, driving a car. She came to my editorial office, more than once, for advice: how to compile a collection of her husband’s stories? How to name the book? But most importantly, to ask: how do I understand the subtext of this or that story?

She was also concerned about her husband’s secret. Roman never let his wife read his prose. Was he shy, knowing her taste and her categorical assessments? Maybe. Was it a matter of trust? Hardly. His life proves it: he loved Maya, was devoted to her throughout their long marriage.

I have a big file of Vershgub’s stories. Sometimes, I reread them. These stories are sad, and at first glance, hopeless. One of them has an epigraph: “Successes are imaginary, troubles are real”. The hero of this novella, Vitaly, a young scientist, who is rightly considered a genius, suddenly refuses to defend his dissertation, leaves his parents’ home, and goes to live with an ugly, much older woman. (“Mama’s son”). Surgeon Sasha, who is known for performing unique operations, suddenly loses his gift and agonizingly tries to understand who is to blame for this, instead of realizing that there is no one to blame. (“The Smith of His Happiness.”) “I recognize real events and real people in the stories,” says Maya. And finally, I guess: the space of the stories was for R.V. a kind of psychoanalyst’s laboratory. In his stories, Roman, who did not believe in God, but trusted fate, sought to penetrate the logic and meaning, or rather, the lack of logic and the senselessness of existence.

At the beginning of April, we ran into Maya on the same Devon Avenue. We hurriedly exchanged news. “Did they give you the book?” — “Not yet.” “Is it out yet?” “Congratulations! What’s the print run of the book?” — “Fifty copies.” — “So few…” — “So many. Thirty books lying around in my closet — no one wants them.”

Maya sighed: “Up there in heaven, Roman is surely judging me…”

*

There are over two million registered authors in the United States. When I think of this, I don’t feel like writing. I imagine an enormous number of ants participating in a contest.

*

But still, in defense of creativity. Man was created in the image of God. What does that mean? Man is — above all — created by the demiurge. Creativity helps the emigrant to preserve a thin, ever-dwindling layer of spirituality.

*

A tragedy of emigration: it gives freedom, but often, instead of opening the world, it closes it.

“What am I to do with my freedom?” This is the sort of question that Efim Petrovich Chepovetsky often asks me. He is in his nineties, but he still writes, and still loves feasts. Samuel Marshak, Lev Kassil, and Mikhail Svetlov, all praised his poems. Once upon a time, millions of children read his books. Many of us still remember their titles: “Myshonok Mytsik,” “Neposedenok, Myakish and Netak,” “About the glorious cow Nasturtia Petrovna,” “Soldier Peshkin and Company” …. I met Chepovetsky more than forty years ago, when I wrote my first book about the “school of Vsevolod Ivanov”. This pioneer of the Russian avant-garde in the 1920s, an oppositional classic of Soviet literature, taught young writers that an artist must search and doubt: this is what matters in art. In February 1972, I published Ivanov’s unknown reviews of “young writers” in Literaturnaya Gazeta. One of the most interesting reviews was devoted to the work of Yefim Chepovetsky. And now, forty-five years later, it is not for the first time that E.P. asks me, insistently: “What should I do with my freedom?”

*

Naum K. died, a grim man who had helped many people without expecting any gratitude in return. And, it seems, he never not received it. Nobody really knew his biography. K. himself told me: during the war he was a scout, ended up in a Stalin’s camp; after release, he rapidly made up for lost time, graduated from the university, quickly defended his thesis, and became famous for his inventions (they were the reason he was not allowed to go abroad for a long time). In his story I was confused by one detail: at the beginning of the war K. was a very young man, almost a boy, but very quickly was promoted to the rank of colonel, and this colonel’s rank was not returned to him after he was rehabilitated. K.’s American fate was obvious: he became a university professor, had graduate students, and created his own firm.

In his huge apartment, overflowing with antiques, K. seems to me a tired traveler who accidentally found himself in an expensive hotel. As if by the way, without giving importance to his confession, he remarks: “I have no one to talk to. I don’t watch television. I only read the news in the newspapers. Everything is quite clear to me.”

Three times a week, K. invariably visited nursing homes, and one day he visited the oncology unit at Lutheran General Hospital. He told me about his visits there, as always, nonchalantly and clearly: “They lie there, abandoned by their children, no one needs them. They have оnly one consolation: it would be even worse for them in Russia,” “When necessary, I become an interpreter — from English, Russian, Yiddish,” “I always read the Holy Scriptures to them. They listen with awe, and as a rule, they don’t understand anything.”

However, K. had his own special attitude towards the Bible. He spoke fearlessly and unapologetically:

“The Torah was given to us by aliens. All reasonable people know this. Aliens are representatives of the Supreme Intelligence. They brought to Earth the moral laws by which mankind should live. How could they not?”

He looked at me inquisitively, with a sly look, as if willing me to discuss the revelation at Mount Sinai. Of course, I did not argue with K.

*

My older friend, the excellent writer Vladimir Ilyich Porudominsky says about Cologne, where he has been living for eleven years: “I am not doing badly here, but this city will never become my past. It does not grow inside me in depth, only in breadth”.

V.I. left Moscow for Germany following the families of his two daughters. He left from the same room where he was born seventy-seven years ago (2005).

*

September 11, 2001. Las Vegas. I decided to meet here with my university friend Emil Goreshter and his wife Dina. The night before, September tenth, we had a wonderful evening, the four of us. In the morning, Emil’s call: “Turn on the TV.”

I watch the Twin Towers collapsing in New York and think: what is this? Is this the end of civilization?

On my way out of my hotel room, I pass through a casino hall. There, on every wall, are huge TV screens that no one pays any attention to. There’s still gambling going on.

*

Turns out my notebooks have long included waking dreams, or rather, dream people.

*

I call him and he comes. Businesslike, calm, he walks around the apartment with a tape measure and a calculator. He is not embarrassed by the circumstances of our repair: my wife and I want to paint the walls and ceilings, but, crushed by fatigue, we decide not to move the cabinets, not to remove shelves with books, not to rearrange dishes and papers in boxes. “Let’s call it a cosmetic repair,” Sergei says with a smile, having understood everything at once. He addresses me without ingratiation, but also without the barely concealed self-righteous boorishness of many Russian craftsmen. He quotes a price slightly higher than the one I was going to pay. I don’t argue, because I already know: I’ll hire him, he is right for me.

Sergei works quietly, almost never distracting me with any questions. I am working on another issue of the magazine, sitting with my laptop in the kitchen, which was painted last year. At noon, I look in the refrigerator and find lunch, prepared by my wife. I invite Sergei to the table. He refuses, pulls out some food of his own from a blue bag. However, he agrees to have tea with sweets. Over tea, answering my questions, he calmly informs me that he is in the country illegally. Of course, I understand the logic of his audacity: in America no one will arrest him for such a confession, but — who knows — maybe I will help him in some way.

I look at Sergei, involuntarily calculating: he is thirty-five years old, eight of them he spent in Chicago. His neatly cut hair is the color of wheat; he has small yet always warm tiger-colored eyes, straight nose, big hands, which, as I have already seen, can do anything. He dresses not quite like a worker, as if expecting to be seen by someone whose opinion is important to him: tailored jeans, a gray flannel shirt. Surprisingly, at the end of the day Sergei looks just as neat, almost elegant.

What attracts me to him? Perhaps it is his calmness, or more exactly, a sense of freedom, which I cannot understand. It would seem that Sergei should rush back to Russia, that he should rush to live, not to spent all this time preparing for life. He left his wife Anya and his children, a boy and a girl, in Tambov. There are no prospects for him in America, but he breathes easily here. He sends money to his family via Western Union once a month, shows me a picture of a two-story house built according to his design. And he doesn’t talk about leaving.

I still want Sergei to stop by sometimes. The closet door in the hallway breaks, the rocking chair made in China falls apart. He fixes everything skillfully, quickly, and then we have breakfast (or lunch) and talk about life. Sergei does not want to take money from me. Now we are friends, or if not quite friends, then buddies. When we say goodbye, I invariably put money in his jacket pocket. Reesigned, he takes it, defeated by my argument: “If you don’t take it, I won’t be able to ask you for help next time.”

Of course, I soon learn the reason for his illogical optimism. “I should introduce you to Rita sometime,” Sergei says. They both live in a so-called Ukrainian village, in a four-family house. They have separate rooms but they are a couple, for six years now. He doesn’t talk again about Rita. Sergei tells me about their commune of illegal immigrants. “I’m sort of the headman there.” I can easily imagine their not infrequent feasts on holidays and birthdays (“We are fifteen people”), their unsentimental care for each other, without which it’s hard to survive here: illegal immigrants can’t easily get medical care. And their sad farewells: from time to time someone buys a one-way ticket, though often they can’t imagine any other life but this strange freedom.

~

“What do you do on Sundays?” I ask him one day when he comes to see me on Monday. For some reason I think that he wants me to ask him this question.

Nevertheless, he is embarrassed, even blushing: “All day long we are in bed. And we’re not tired at all.” His eyes light up — the usual, slightly ridiculous male pride. “And you know, sometimes when I wake up, I forget where I am. Then I think: I’m still in my village, and this is the first sweet year after my wife and I got married.”

~

I never got to meet Rita. I saw her only once in August — on a video on Sergei’s phone. She told him about her departure the day before her flight. “She couldn’t tll him earlier. She didn’t make up her mind. And I don’t blame her. Rita’s eldest son is getting married in Kaliningrad.” She walks to the landing without looking back. Small, as if frozen, in a fashionable summer suit, attractive even in her hopeless despair. (2016, Dec.)

*

The Joy of Oblivion. The topic of an essay that I have wanted to write for several years now, when I suddenly realize: this idea has become obvious to many.

As we know, accepting death, agreeing with it is one of the stages on the last path of man. But, as it turns out, one can humbly accept one’s remorselessness. And even find joy in this state.

…On Thursday Yura and Fira come for a visit. Confused and serene at the same time. They want to tell me about their recent choice, an unusual choice. “You know,” says Fira, “in the late seventies, Yurochka was dragged to the KGB for interrogation. Yes, for being anti-Soviet and a dissident. Then everything seemed to have calmed down, settled down. But many of Yurochka’s manuscripts, seized by the authorities, remained with them. And now, imagine, a young researcher from Moldova found us. And now we’re dumbfounded by the news! He found Yura’s play in the KGB archive. What play? It’s about daily life in ancient Rome. But permeated, as was customary at that time in liberal literature, with modern allusions. The play is brilliant! says the young man on the phone. He says they want t publish it. And he seems to have already agreed with editors of some anthology. And we’re at a loss. Yurochka claims that he never wrote that play at all. But I wasn’t there for him at that time. Maybe it’s confusion, some kind of Gabash setup? In short, we decided to abandon this publication. What’s it for? What will it change in our lives?”

I watched them from my window: they were walking along Devon Avenue, unhurriedly, as always. Yura, as if back in his childhood, is afraid to let go of his wife’s hand. And the great joy of oblivion, for the first time consciously chosen and accepted by their souls, makes them happy.

*

Many people resent vulgarity; it pervades everything in emigration. Yet vulgarity is the only unchanging soil of emigration.

*

A Russian restaurant with a pretentious name “Zhivago,” typical in emigration, opens near a cemetery. There are always customers in the restaurant: after the funeral, people come here to pay their respects. I like this. Remembering the deceased, people think of themselves. They say, and what about you, dear, you are not eternal. What did you do, what did you have time for? You adapted, you lied. You buried your talent so deep that you can’t even find it. Ahead of you, like ahead of everyone else, is an earthen pit covered with cement slabs. But in these reflections, under a shot of vodka, there is a sneaky joy that you are still alive, still alive!

*

I always feel sorry for Russian doctors in America. Their path is predetermined and difficult. They arrive with diplomas from Russian medical schools when they are already over forty. They take exams (in English, of coursе) to confirm their diplomas. They study for several years in a residency program (just try to get in!). And they still have time to become millionaires.

*

“And your guts slap on the asphalt,” Dina Rubina writes about the first days of emigration. In late August and September 1996, the asphalt in Chicago melts from the heat. Our past life disappears without a trace — as if it never happened. And the new life does not begin…

It’s the same with everyone else. “Depression creeps in gradually. The world becomes dark.” This is Olga G. Although now she also shares her joy with me: “It’s as if I’ve been born again. It’s as if someone took the dark bag off my head.” (May 1, 2007). For how long?

*

Sasha G. confesses: “While driving the car, I sing. Strange as it may seem, it’s only two songs. “Okurochek” by Yuz Aleshkovsky and “Come on, boy, raise the gate higher…”. “I often sing them even when I’m traveling with my wife. It annoys her: for years — the same thing”. Has anyone ever thought that works on the prison-camp theme are important for emigrants as a kind of psychotherapy? In times of deep sadness I reread Shalamov’s most depressing stories.

*

Is emigration a dream? You open your eyes and — there is nothing. Come to think of it, how little remained of the Russian literary emigration of the twenties-thirties of the last century. Only the brightest names reached us, mostly the ones that had been known in pre-revolutionary Russia. And how many young talented voices never reached us. Their creativity remained a bitter mention – in other people’s letters and diaries. I am discussing this with Oleg Korostelev, a literary scholar. He created a miracle: reconstructing the life of the literary emigration of the 1920-1930s, he accomplished more than a whole scientific institute. And yet the failures of literary memory are enormous. And often, they are irreversible. One of my naive questions to Korostelev is “How can we make sure that this kind of thing does not happen again?” (You can read our conversation in Seagull Magazine, June 10, 2016).

*

Fifteen minutes before the Russian bookstore closes, an old woman appears on the doorstep. On her head is a white panama (a memory of her distant pioneer childhood). In her hand is a large straw purse: my grandmother used to go to the market with such a purse. This is not the first time the old woman is here. She goes straight to the shelf with books on esotericism. She is looking for something tensely, hurriedly looking through the tables of contents.

“Can I help you?” The saleswoman asks her.

“No, I can find it myself,” says the old woman firmly. She looks at her watch and, realizing that she arrived too late, has to ask for help: “I need a book on how to change one’s fate.”

Is it funny? Hardly. Again, the same theme characteristic of emigration: a change of destiny. (2008, April)

*

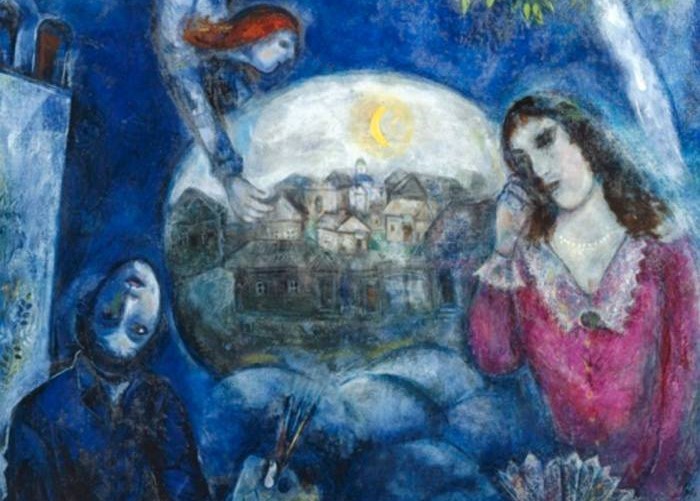

While I answer questions for “Khreshchatyk. Perekrestok,” the Russian-language journal based in Germany, following its anniversary in 2017, I suddenly remember how surprised and happy I was, after moving to Chicago, to find 21 Russian bookstores in the city. Five of them were very close to my home. Strangely enough, each store had its own face. One sold the latest novelties delivered from Moscow by plane. Another one was owned by a graduate of the Litin Institute; without a thought of profit, he ordered Russian and translated editions imbued with the spirit of experimentation. In the third one, I was attracted by monographs on art, albums of artists’ reproductions. However, I am sure: the most amazing one was the House of Russian Book. Here, among paintings and engravings, collections of works, and many rare editions, I was always waiting for unexpected finds. And if you were in the mood to ask questions, Ilya Rudyak, the hospitable owner of this festive kingdom, a writer and director from Odessa, would talk about almost every book inspiringly, as if reciting poetry. I often went there to talk, to breathe the special air, no, not book dust — the air of Russian culture. By the way, the great book lover Yevgeny Yevtushenko loved to come here as well.

…All these stores have long gone out of business. Their owners, mostly naive idealists, went bankrupt. Now books in Russian are sold in Chicago in three kiosks: one nestled in the “Russian gastronome”, and two, in so-called “Russian pharmacies”.

Of course, American bookstores are constantly closing, too. Palaces made of several floors, where one can spend a whole day, they are filled with books and magazines that you can not only look at, but also read. Here you can drink coffee with friends or have a snack. And then again venture bravely into the sea of books. Except that there are fewer and fewer travelers.

Leaving for America, I painfully said goodbye to my library, which I had been collecting since I was twelve years old, with passion I did not understand myself. Of course, many people felt the same way. Now we say another goodbye: to Readers of Books. They are leaving with frightening speed. It seems to me, more and more often, that emigrant publications are read only by their authors. (2017, Dec.)

*

An invasion of fortune-tellers, clairvoyants, and hereditary sorcerers. Ayun-batyr, a Siberian shaman, cures infertility during individual sessions. Bonifatius, a Contactor with the cosmos can change your fate … My friend M.K. had an appointment with a contactor. “Did he help you?” “Yes, he helped me a lot! I’m lucky: I bought the right to go to Bonifatius anytime, no waiting in line. I can call him and get his advice in any difficult situation.”

“How much did it cost you?” M.K. hesitates, not really wanting to talk about the price he paid, it’s not customary in the West. But then she remembers our friendship and says, “Five thousand.”

M.K. didn’t inherit her money. My sympathy for this heavy, aging, still beautiful woman has to do with her courageous resistance to emigration. She came to America at fifty, without any English, with a sick husband and two teenage girls. She once explained to me: “One was my husband’s daughter from his first marriage, the other was our daughter. The husband died a year later, so we had to decide what to do, quickly… And, like many people, I decided to clean other people’s apartments.” At the same time she learned English, started to drive, passed an exam confirming her qualification as a laboratory chemist (in her previous life she was a research chemist, head of a large laboratory). She counted every dollar, gave her daughters a good ducation, bought a good apartment.

M.K. is not an idiot. But she is lonely: her daughters are busy with their own lives. And she’s been diagnosed with cancer. And she has to choose between surgery or waiting. The Contactor, a sweet young man with a determined look, tells her what she wants to hear: wait. After a concilium of doctors, M.K. has the surgery, after all. “Do you communicate with Bonifatius?” I ask her a few months later. “He’s become difficult to contact,” M.K. says without judgment. Perhaps she is still thinking of the higher powers intervening in her life.

*

A cover of a Russian-language Chicago weekly has a portrait of a priest in church vestments. And his words, in quotation marks, next to the picture: “I apologize to everyone!” Michael Ts., a priest of the Apostolic Orthodox Church, gives an interview to a journalist. He fervently repents his sins. In 1978, in Kyiv, he dreamed of becoming a priest but instead became a KGB agent. M.C. himself suggested his pseudonym: Atos. (The pseudonym was not accidental: the future batyushka** was a fencer, a master of sports). After leaving the KGB and coming to the United States, he discovered a different calling: he started making international driver’s licenses for illegal Mexicans. One day, he says, “Special Forces swooped in and I was declared almost the godfather of the Russian mafia in Chicago… I got out of jail on bail, and got a suspended sentence.” All this happened a long time ago, he says, twenty years ago. Now his voice trembles, “I would like to apologize to everyone for my sins and mistakes.” But that’s not all. M.C. makes a final gift to his readers: “In Chicago, I am the only priest who, given our ‘battlefield conditions,’ takes confession over the phone…of course, completely free of charge.” (Apr., 2018)

*

Does a person have a premonition of his or her death? The answer is obvious. Immediately, I recall many stories. But I will tell only one, my own.

Like everyone else, I often heard stories about attacks in “bad” neighborhoods of Chicago. The advice of experienced people: in no case should you argue, run away, resist, call for help…. Give what you can and what they want. And best of all, have a small amount of money in your pocket (what if there is a drug addict with a disturbed mind in front of you? He won’t hesitate to shoot or hit you).

Last Saturday I was walking home from a synagogue. It was about one o’clock in the afternoon. It rained in the morning but now it was dry and a little frosty. I walk, thinking: “Here is the life that has passed…. No, not like that. Gone is the uncertainty of youth. Now everything ahead is clear. Only one thing is not clear: what the end will be and when will it come…”

It is said that when souls descend into this world to put on flesh, the exact date of our departure from here has already been determined. So is the mission which we came here to fulfill. Of course, the Most High gives a person a choice: the route of our earthly path depends on ourselves. But the final date cannot be changed.

Such banal thoughts…

A walk takes me about fifteen minutes. Suddenly, in one of the alleys (near a construction site of modest two-million-dollar mansions), two young men catch up with me. Both are about eighteen. Both are decently dressed. One runs ahead, extends his arm to me: “Good shabes!”

And immediately, with a different — threatening — intonation: “Give me your money …. Fast. Otherwise I’ll shoot you.”

He dips his hand into his jacket pocket, takes out a revolver, hides it again, points the muzzle at me through his jacket.

Why am I calm? Maybe because I immediately recall my musings of just a few minutes ago. Is this really how the Almighty was preparing me for death?

“I have no money.” It’s true. On Shabbat, Jews aren’t supposed to have money with them.

They look around. There’s still no one in the street.

“I’ll count to three, then shoot. One… two…”

He counts to eight. I’m waiting for a shot. Is this really it?

As if on cue, I suddenly take off my new Italian coat:

“This is for you!”

Realizing that I really don’t have any money on me and ignoring my coat, they turn around and leave.

~

Four days later, the whole thing still looks strange.

Odd: on Shabbat in our neighborhood, where most residents are orthodox Jews, there were no passersby on the street (and the synagogues had just finished services). The odd thing is that they showed up here. And another odd thing is that they left silently…

~

Was this a rehearsal of death or just a waking dream?

_________________________________________________________

NOTES

* Doctor’s sausage* (doktorskaya kolbasa) — a sausage popular in the Soviet Union

** batyushka — a priest; literal translation: father