“You’ll work with us,” said the man who invited me to the interview, confidently. “We need educated people.”

It was back in 1995, when I had grown tired of working in a nursing home for people with Alzheimer’s disease and was trying to get a job as a dental assistant in a successful office in New Jersey.

I was interviewed by the clinic’s chief physician, Dr. Ross. He was a short, balding man in his sixties, whose skin and entire appearance glowed from creams, ointments, massages, manicures, baths, and other treatments.

When he heard about my Russian dental degree, he hired me on the spot. During our conversation, the doctor told me that he had three large clinics, that they worked five days a week, 12 hours a day with a half-hour lunch break, that he had excellent doctors working with him, but that not everything was always in order with the assistants—not all of them were diligent, some were late for work, and some even got pregnant unexpectedly, disrupting the doctors’ work schedule. I listened to him carefully, answered his questions, and, delighted at the prospect of a change of scenery, didn’t even ask what my duties would be.

All night long, I imagined my future job. I imagined how I would arrive early in the morning at this chic office, how I—a doctor from Moscow!—would be introduced to the staff and put in charge of this whole bunch of assistants so that I could bring order, properly organize their senseless work, and ensure that all health and safety rules were followed.

I woke up early. I washed, shaved, got dressed, and even sprayed a little cologne on my cheeks, then smeared some butter on my forehead (to show that I’m not a bumpkin, that I also know how to take care of my skin, after all, I’m not from Syzran*, but from the white-stone city* itself), got into my old jalopy and drove across the Delaware River bridge connecting Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Forty minutes later, I was already at work—thirty minutes ahead of schedule. Because the boss always has to set an example of punctuality.

Work started at 9 a.m. At ten to nine, three shiny cars—a Porsche, a Mercedes, and a Jaguar—pulled up to the clinic. The doctors jumped out, waved at me, and went to drink coffee in the kitchen.

At five minutes to nine, the assistants’ beat-up cars pulled up. Sleepy faces of various shapes emerged from them. All of them were holding boxes of pizza and doughnuts in their left hands and cardboard cups of coffee in their right. One of the faces was visibly pregnant.

Dr. Ross gathered everyone in a spacious meeting room, sat us down at a table, and introduced me.

“Here,” he said, “an experienced doctor from Moscow. He’ll be working with us.”

I smiled broadly and kindly at everyone. In response, they nodded sleepily.

“All right, everyone!” shouted another doctor. “We’ve had our coffee, let’s get to work!”

Everyone put on beautiful disposable gowns and gloves. The doctors took binocular glasses out of expensive cases and put them on their noses. In a second, this gathering of sleepy people turned into a swarm of bees. They ran orderly through the numerous rooms of the clinic. Some quickly wiped down chairs, others even more quickly seated patients, of whom there were already a great many in the waiting room, while still others set out instruments. Pregnant Tara (that was the name of the assistant who had rushed in unasked) flitted about like a dragonfly, moving at the speed of sound from room to room.

I stood and watched all this commotion with my mouth wide open. I tried to figure out when I should start giving orders and what exactly I should say. The tension made beads of sweat appear on my forehead, which the butter made even more noticeable, and I looked like a rose that had been sprayed with water before being sold. I understood my own value and beauty, but I had no idea how to apply them.

Five minutes passed before Tara flew up to me, buzzing with all six propellers, and shouted: “Well, doctor from Moscow? What are you standing there like a dick after Viagra? Get to work!”

Well, no, Viagra didn’t exist back then, but she shouted something offensive.

I stared at her with a smart look and squeaked quietly, “What am I supposed to do?”

Then she grabbed me by the scruff of my neck, dragged me down the corridor with her strong arm, and threw me into a small room lit by a dim lamp, where there was a table, a sink, and several brushes with metal bristles lying next to the sink.

“We’ll bring all the dirty instruments from the three rooms here. And you’ll clean them thoroughly with these brushes and put them on these trays,” she said, pointing with her chubby hands to the table and the trays.

“And then I have to take them to be sterilized?” I asked quietly, hoping that I would be entrusted with at least something related to medical work.

“No, what are you thinking?” Tara smiled. “Sterilization requires knowledge and skill. Get cleaning! And hurry up. You’re wandering around here like a slacker!” She smiled and added, for some reason, “like a Russian bear” (offending all Russian bears with this remark).

I set to work. The bees brought me trays with used instruments, and I scrubbed all the tips, tweezers, files, forceps, and probes with brushes, cleaning them of blood, dirt, and pieces of flesh. The instruments arrived in huge batches, and I scrubbed them for four hours straight without stopping. Three times they returned the trays to me, demanding that I redo the work. I worked in a half-bent position. By twelve o’clock my back was aching. At one o’clock my arms and legs were aching. I cursed everything in the world and encouraged myself with the thought that Dr. Ross was just testing me. That he would soon see all my diligence and immediately appoint me chief. I didn’t know why exactly chief, but I was sure that as chief, for whatever reason, I would be more useful to him.

Finally, at half past one, Dr. Ross came into my little room.

“Eric, come with me,” he said quietly.

“Finally,” I thought. “It’s happening,” and I followed him.

We went into one of the offices.

“Meet him!” my boss exclaimed happily and pointed to a chair. “This is Michael!”

Sitting in the chair was a heavyset man in his fifties. He was wearing a beige shirt with the top two buttons undone. He had on well-pressed dark brown pants and clean, shiny dark burgundy shoes.

“Michael is from Moscow!” Ross explained happily again and turned to Michael. “And this is Eric. He’s also from Moscow. Do you know each other?”

I looked sadly at Mikhail. He sat with his mouth wide open, which was covered by a metal frame; a green rubber band was stretched across the frame — that horrible device that makes the dentist’s job easier when he cleans root canals, but makes it impossible for the patient to say anything. All I could see of Michael’s face were his large protruding ears, a white tooth gleaming from under the rubber band, and his large eyes with olive-colored pupils, which Misha rolled around in surprise, muttering something.

“Nnyyy znyyy,” I heard his muffled voice.

“I don’t know him either,” I said wearily to Dr. Ross. “Moscow is a big city,” I added. And seeing the disappointment in my boss’s eyes, I said, “But we both know the bear.”

“What bear?” the doctor asked, surprised but pleased.

“The one that, when he drinks vodka, walks around the capital playing the balalaika,” I added confidently, looking boldly into my boss’s eyes.

Ross thought for a moment. It was clear that he was trying to remember or understand something. Finally, it dawned on him, and he smiled.

“You’re joking, Eric, right?”

Without thinking, I replied that I wasn’t joking. And I left the room, from which I could hear the bubbling and grunting of Michael, who was in high spirits.

I didn’t go into the dark room. Instead, I went into the kitchen. Because it was lunchtime. It was the official half-hour break time. All the bees, having folded their wings, sat quietly at their desks and quickly but wearily chewed pizza and doughnuts, holding them in their hands.

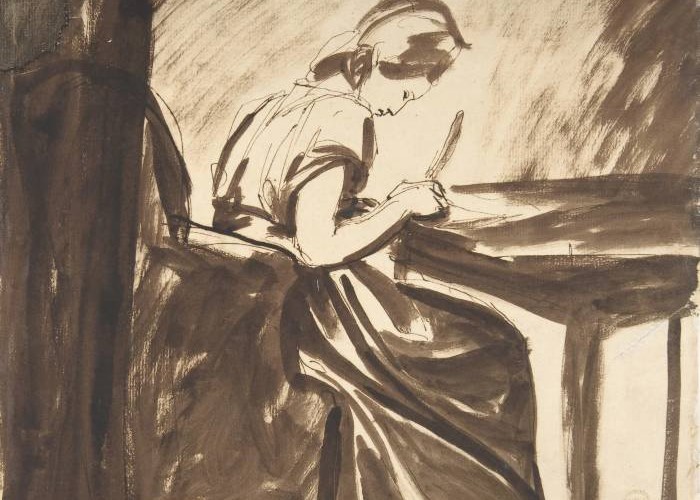

I silently went to my bag and took out a small plastic container with cutlets and mashed potatoes. I went to the microwave, heated up my food, sat down at the table, took a knife in my right hand and a fork in my left, and began to eat beautifully and solemnly.

After all, I was a doctor from Moscow.

______________________

NOTES

*”I’m not from Syzran, but from the white-stone city” – Syzran is a provincial city in Russia. The “white-stone city” is Moscow.