Kamil Galeyev’s story of the conflict between two types of elites – the landed elites (Barons) and the courtiers (Courtiers) – can be seen as a particular example of the functioning of two competing but interrelated types of capital: material and symbolic (or, if you like, symbolic first-order (money) and symbolic second-order (power). It is clear, however, that the social hierarchies in which rents are redistributed can be based on both of these types of capital, and the nature of power flowing down the steps of the sacrificial pyramid and determining strategies of a struggle for more profitable places in its internal hierarchy is always of a mixed nature.

Such an optic allows us to take a new look at the transition from an autocratic system to a totalitarian one, the various signs of which Yudin recently spoke about. As the main signal of this transformation, he cites the permission to create new horizontal structures that are allowed to produce ideology “from below”.

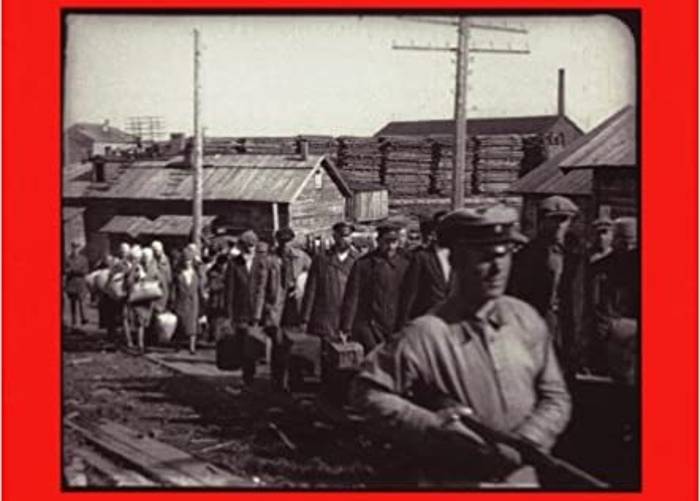

The reasons for this transition can be understood economically. When material resources, the control over which is distributed through a system of feeding down the pyramid of endlessly sprawling court power, consisting of thousands of officials, begin to run out, the top of the hierarchy must begin to cut the flows going to the lower floors (in particular, to the Barons) to maintain their usual level of comfort.

But disgruntled sub-elite groups are a direct threat to the Court which, in order to keep its position, needs to offer something to them.

This something turns out to be the right to create new hierarchies, built not so much on the distribution of material capital as on the distribution of symbolic capital. In these new hierarchies, they are given the right to occupy the top positions, while those below them are given new strategies of competition – this time not for material goods, which no longer exist, but for symbolic status.

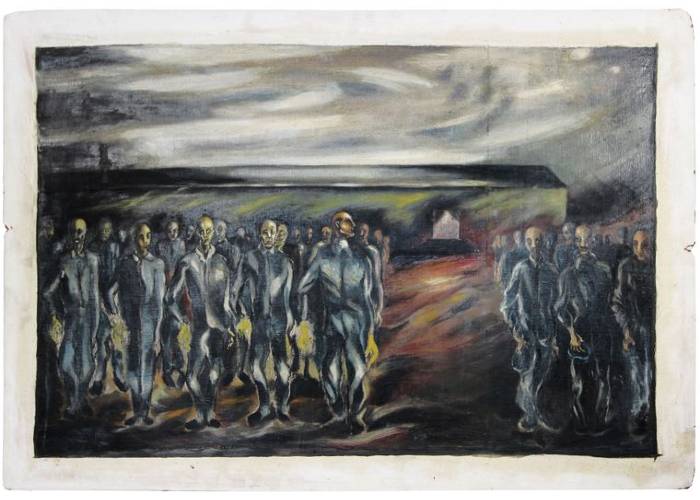

Pioneers, Komsomol, Cossacks, neighborhood brigades, and druzhiny are all characteristic examples of such new formations, which allow the system to remain stable by transferring the capital to the symbolic realm. Within the new pyramids, new models of the struggle for resources, now symbols, and new signs of status begin to emerge: shoulder straps, armbands, badges, neckties, boards of honor, etc.

Fortunately, such a transition is impossible outside a powerful ideological and mythological project capable of producing new symbolic capital.

II

Much has been written about the mythological background of the Russian ziggurat and its historiosophic foundations, both by the servants of this apocalyptic cult (starting with the pharaoh himself and his courtiers and ending with the half-mad priests) and by its researchers and vivisectors.

Leaving aside a detailed analysis of key mythologies, I would like to point out the fundamental connection between their inner forms and the socioeconomic models of redistribution of symbolic capitals of any order generated by them.

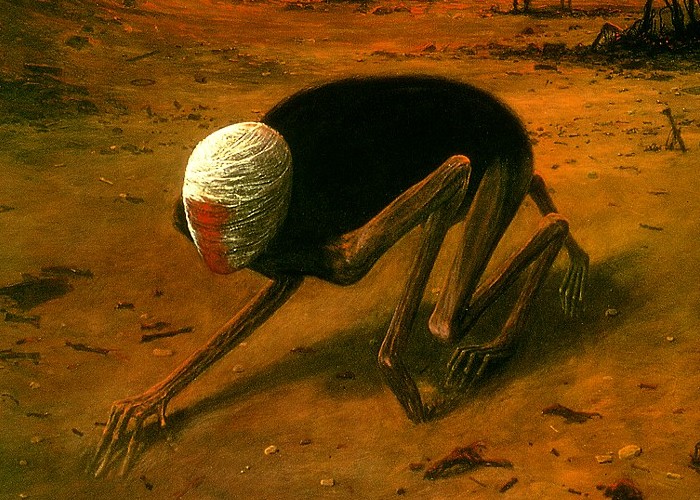

Nevzorov’s recent heroes, the cannibals, whose eating behavior he so deliciously and expertly described, exist in such a mythological or, more precisely, cosmological model within which their behavior is not simply logical, but corresponds to the inner form of the main or generative myth of their community.

We know that in traditional societies moving up the ranks of the social hierarchy is associated with a renewal of status requiring the performance of special rites of passage. For a boy to become a man, a hunter, he must perform a symbolic action, which, depending on the proto-mythologem of the tribe (from the legend of his magical ancestor) could be eating the brain of the enemy or, for example, hanging himself up on hooks by the skin on his back.

But the connection of various procreative myths with the logic of status change can also be traced in more developed societies, even at the macro level.

Thus, in Russian history, the folklore model of crossing the border between two worlds and obtaining a magical artifact, tool, or symbolic attribute is repeated many times. Examples are the calling of the Varangians, the two marriages of Prince Vladimir – to Princess Rogneda, a Varangian by birth, and to the Byzantine Princess Anna (this second marriage begins the unfortunate Crimean myth of Russian history), as well as Peter’s European journey.

However, this is only one such myth-logic.

Incidentally, Camille’s recent observation about the unconscious reproduction of the travesty image of the Enemy can also be interpreted as a reverse version of the same plot, in which the artifact obtained “over there, on the other side”, where it is an attribute of the monster, becomes an attribute of the hero’s renewed status (for example, the skin of the Nemean lion) “here”.

The influence of the internal form of myth on the properties of the system it generates is not limited to the mechanism of advancement in its hierarchy but extends to its other properties as well. Reproducing on all floors the model set by its own apex (be it a magical ancestor, a mythological hero, a prophet, or simply a ruler), the elements of the system in all their interrelations strive to reproduce its (the vertex’s) properties and strategies.

I recall Arestovich’s recent remark (by the way, note the structure of the name: Ares is the god of war) about the fundamental difference between the guerrilla logic of the organization of Ukrainian detachments, which can disband and reconvene as many times as desired, and the strict vertical hierarchy of Russian troops, which lose their combat effectiveness when the guiding will is removed.

This reminds me of Vyacheslav Ivanov’s reflections on the Legion and Sobornost’ as two fundamentally different ways of organizing elements in systems. By the way, here is another curious shift. The article was written during the First World War and contrasts the German “machine mentality” with the Russian Orthodox “organic mentality”. The entire current situation can be interpreted in the spirit of Ivanov’s opposition. In the context of contemporary Russia, which contains within itself the possibility of both paths, this idea is beautifully developed by Pastukhov.

The clash of the two historical myth-models of the Slavic culture, embodied in conflicting political systems, is written today both by regime ideologists who speak of anti-Russia, and by somewhat more educated people who speak of the opposition between the Moscow Rus’, which inherited features of the Horde statehood, and the Lithuanian Rus’, which is closer to the European feudal model. It would be lovely to point out the opposition between the myth of the serpent-bearer (Saint George on the coat of arms of the Moscow principality) and the proto-Christian myth of the suffering deity, but it doesn’t work, at least not at the level of official heraldry (e.g., he Hunt on the coat of arms of the GDL).

What is important now is not a specific analysis of the myths actualizing today, but a general indication of the possibility of interpreting national and more broadly civilizational conflicts as the results of the opposition of the underlying derivative mythologemes – as clashes not only of states but also of their Cultural Heroes.

III

The post-structuralist, post-colonial, liberal, and post-modern trend in European culture in the twentieth century toward the struggle with mythology, which has its roots in the Enlightenment Project, should be recognized as a failure.

This is not only about the repetition of the unlearned lessons of the 20th century, not only that this monstrous repetition successfully justifies itself with the mythologemes of the day before yesterday.

The Leviathan of totalitarianism not only does not sink but also adopts the techniques of deconstruction. It builds its propaganda on the well-absorbed techniques of postmodern aesthetics.

Ultimately, poststructuralist, postcolonial critique itself can be seen today as a derivative of myth. This means that the weapon capable of defeating the dragon can only be found in the actualization of other alternative-producing mythologies.

In the clash between Slavophiles and Westerners, it is foolish to side with the West: this fight has already been lost more than once. The monster of the empire is successfully reassembling itself, growing new nuclear warheads.

Weapons that kill it must be sought in its own lair in the realm of the myth.

But rationalism’s fear of mythology, its reluctance to resort to it (or its fear of admitting this reluctance), does not arise out of nothing.

In order not to replace one dragon with another with our own hands, we need to be very clear about the consequences of using one weapon or another.

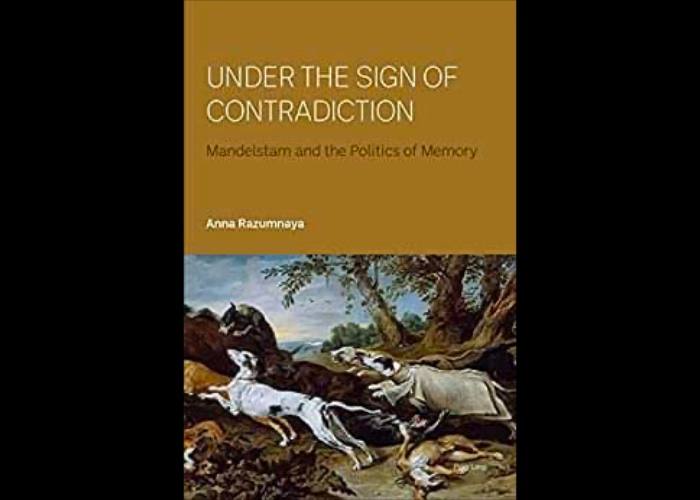

We have a huge cultural arsenal at our disposal: from ancient Ladoga to Novgorod veche, from Free Ingria to, God forbid, Hyperborea, from Veshyi Oleg to Alexander III, from Peter the Great to Alexander Pushkin, from God-building to God-seeking, from a bathhouse with spiders to the endless expanse.

But in looking at the fatal mistakes made by our culture today, it is important to remember that in the search for cultural heroes and myths, on which the new Russian dream might be built, we should focus not only on their recognizability, marketability, and trendiness but also on what strategies and practices of symbolic capital distribution in the socio-economic hierarchy will turn out to be built on them and their likeness.

Here, however, is already an inaccurate turn of phrase. Myth in this building is more of a capstone than a cornerstone.

The original (in Russian) was published in Syg.ma on April 5, 2022. The English version is published for the first time.