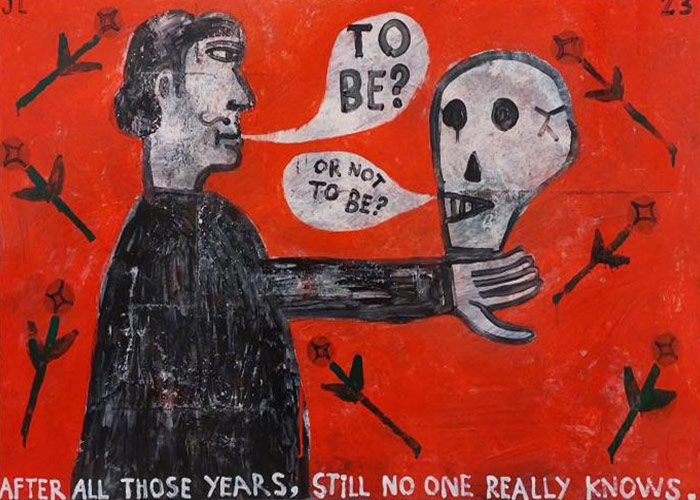

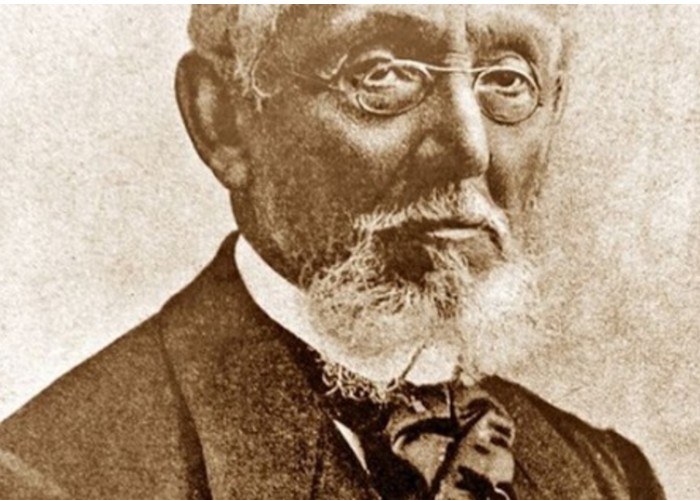

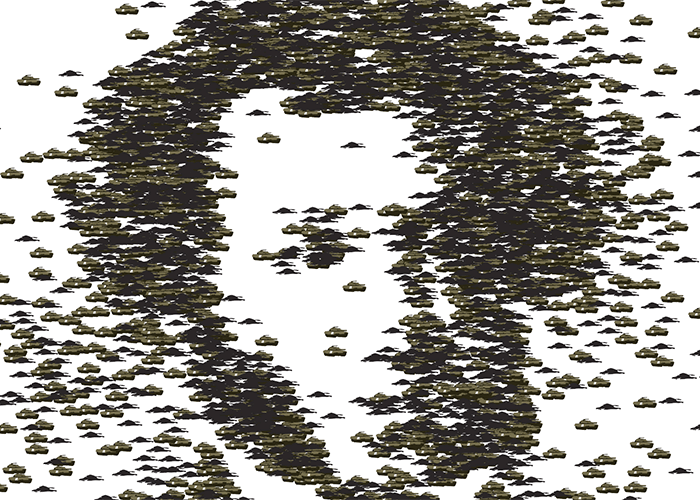

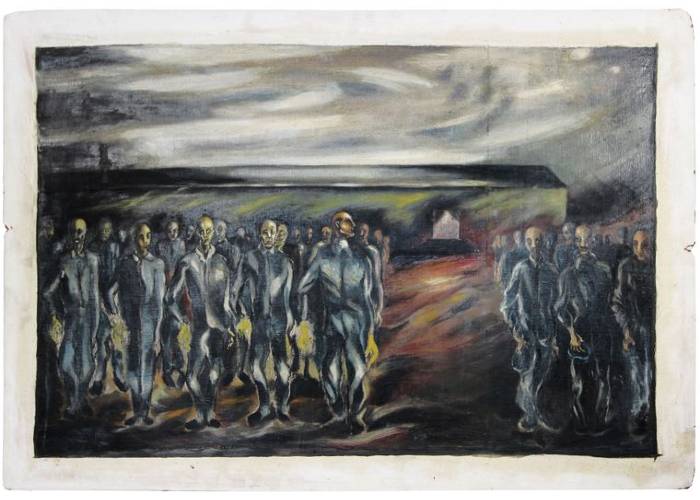

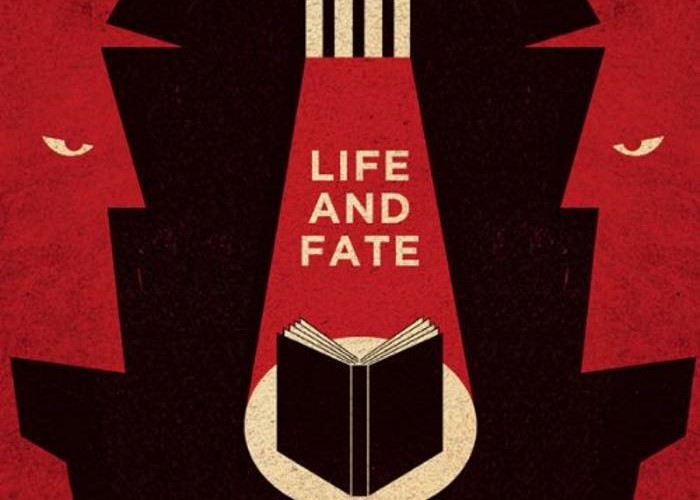

Grossman’s novel “Life and Fate” is neither forgotten, nor unread – it is included in the school curriculum, and even those who have not read it, have a rough idea of what it is about. Nothing else is needed, it seems, for it to be present in the culture’s awareness, yet somehow it does not arouse interest. It is not referred to in debates or argued about. Even the most vivid episodes, classical in their simplicity and precision – for example, the one where physicist Strum makes a scientific discovery after several hours of talking about politics, or the one where General Novikov delays a tank attack for eight minutes, resisting the force of an order issued at the top – these episodes are not remembered and do not come up in conversations. Until you begin to reread the novel, it seems that its points about totalitarian regimes are written in a correct, naive and traditionally banal form, the way things are often written for schoolchildren.

The form of the novel is completely original, but its originality and beauty can be seen not so much at the level of its verbal constructions (Grossman’s words are precise and clear but they lack any magic) as at the level of its structure. Its form is based not on insights but on decisions; a bridge or a skyscraper can be beautiful – and in this, Grossman resembles classical authors who were more like modern architects and engineers than writers. This similarity is not only formal.

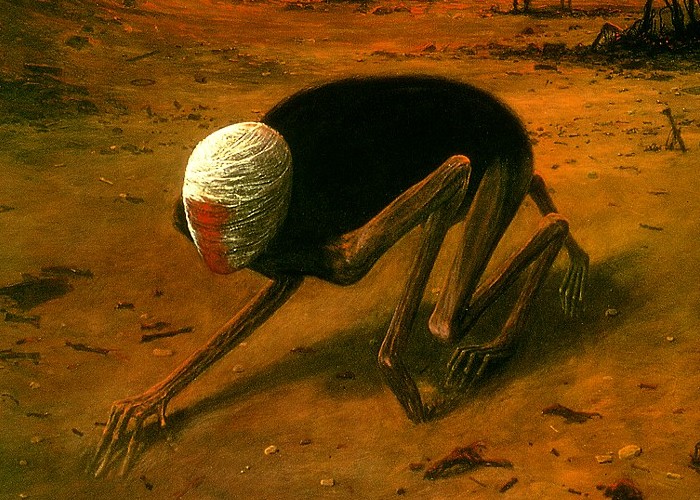

Grossman’s central idea is that the highest value in the world are instances of humanity that occur despite an inhuman force that destroys people’s humanity. This idea of his is utterly classical in spirit. “An invisible force was pressing down on him. Only people who have not experienced it can be surprised by those who submit to it. Those who have experienced it are surprised by the opposite – by the ability to flare up even for a moment, to let out even one angry word, a timid, quick gesture of protest.”

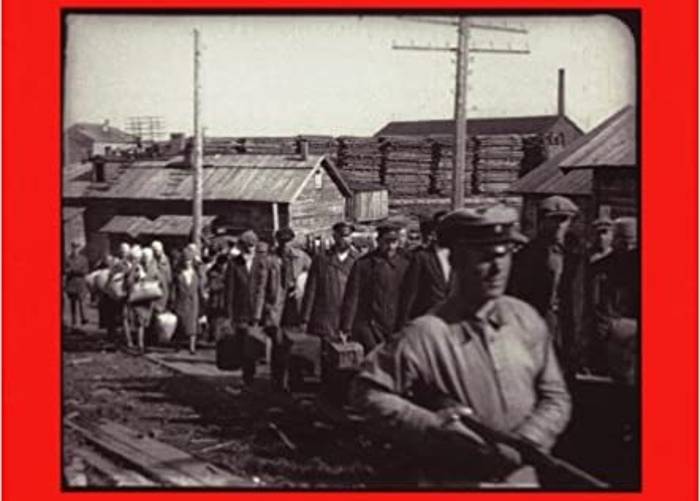

This is the idea that the modern, civilized society considers naive. Yet here’s an idea that seems not only not naive but profound and mercilessly sober: if you have fallen into an evil system, that is, practically into any system, there is nothing to hold on to: there is no humanity to be preserved here. Either you’re outside of any system or you become a monster, there’s no running away from it. “There it is, the truth about the world and man! Ah, how profound!” we say about any book that reaffirms this idea. We appreciate this totality and hopelessness in our local idols like Sorokin and Pelevin as well as in trendy translated authors like Littell, the Frenchman who wrote a pretentious parody of Grossman’s novel, and we even manage to interpret Shalamov in the same spirit.

The claw is bogged down and the bird is a goner – that is the highest wisdom. The only way for the bird not to be a goner is to be alone, to be that impossibly lonely hawk from Brodsky’s poems. In reality, this way of looking at things means that a person serves the system – whether public, private, big, or small, in short, any system – unquestioningly, and at the same time feels himself to be a bird soaring above it all. The consciousness, intoxicated by the fumes of passive merging with the system as well as by its imaginary supra-worldly loneliness, cannot see the only interesting people in reality – a judge or a doctor standing his ground, despite the environment. Grossman’s novel, which is sober, clear, without any magical or intoxicating elements, and his realism, in which one is always part of a system – the army, the camp, the institute, the editorial office, etc., must seem naive and banal to this consciousness which overlooks one thing that matters the most: that one’s humanity cannot be destroyed without one’s consent.