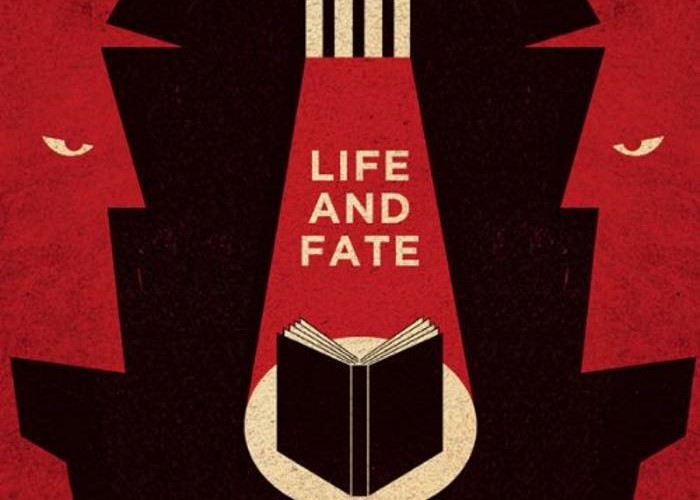

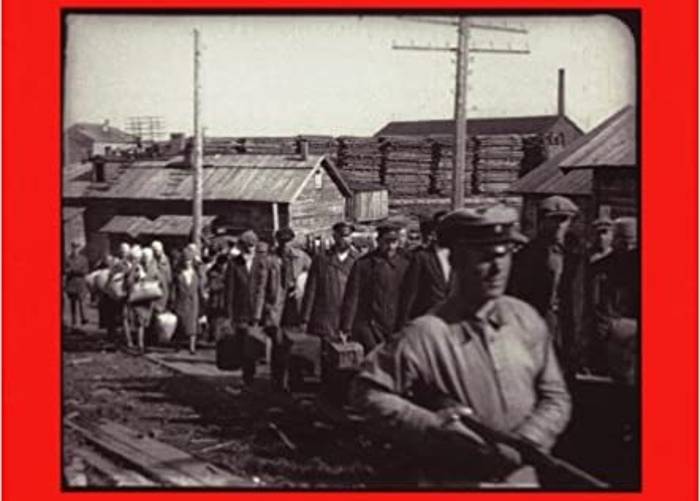

Gulag: Life and Death Inside the Soviet Concentration Camps

By Tomasz Kizny

Published by Firefly Books

Hardcover; 496 pages

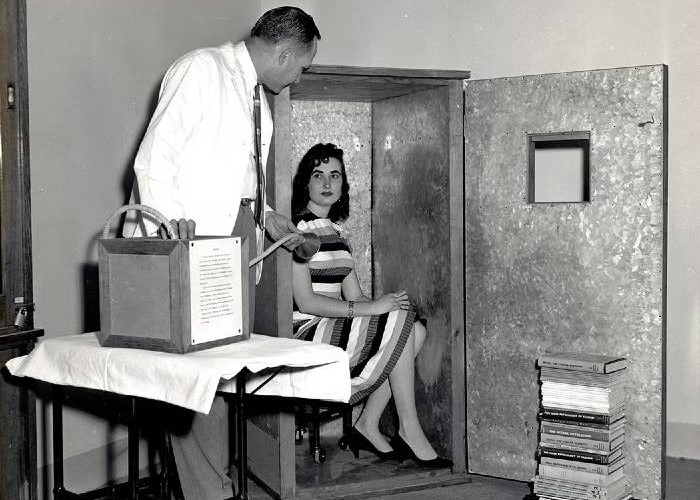

To write a brief review of this book strikes me as almost a sinful act, considering the scale of the human tragedy that is painstakingly documented in this collection of more than 500 photographs. Norman Davies contributes a moving, thoughtful introduction that attempts to explain why so much of this human catastrophe has gone unnoticed — the deaths of millions of people. The enduring communist sympathies of many European and North American intellectuals is one disconcerting reason. But principally what accounts for this lack of historical awareness is the fact that, while alive, Stalin devised means of keeping all information about the camps strictly secret (the camps covered one-tenth of the old Soviet Union’s entire territory). Davies elaborates: “Systematic descriptions and statistics did not begin to emerge until the Khrushchev era, when the worst excesses, including the widespread use of slave labor, were abandoned.” Even afterwards, “Sovietologists had consistently denied both the scale and the murderous nature of Soviet political repression.”

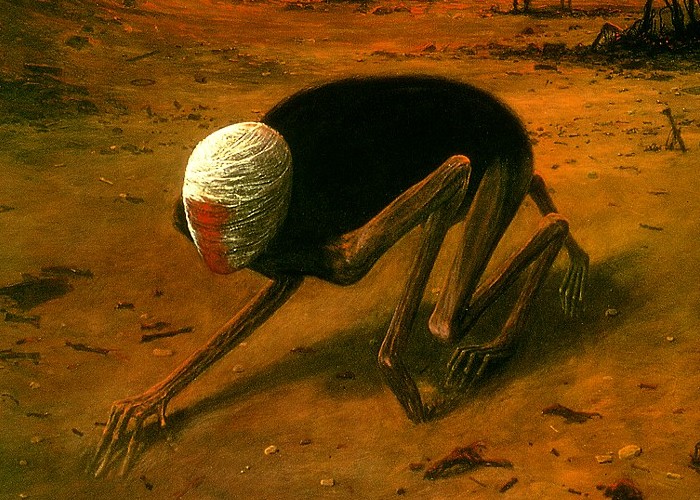

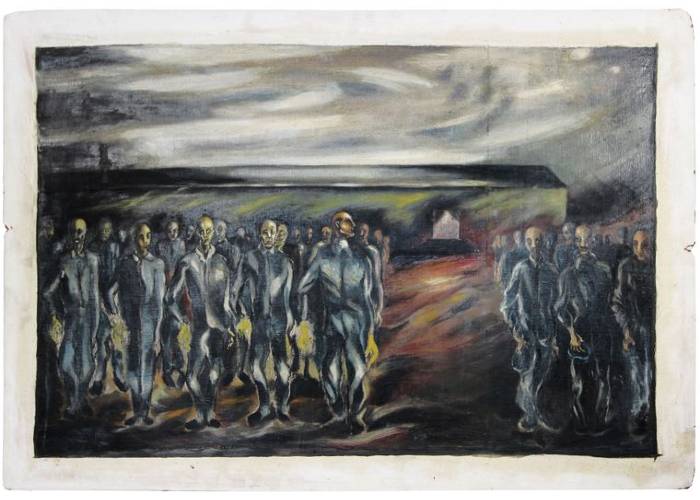

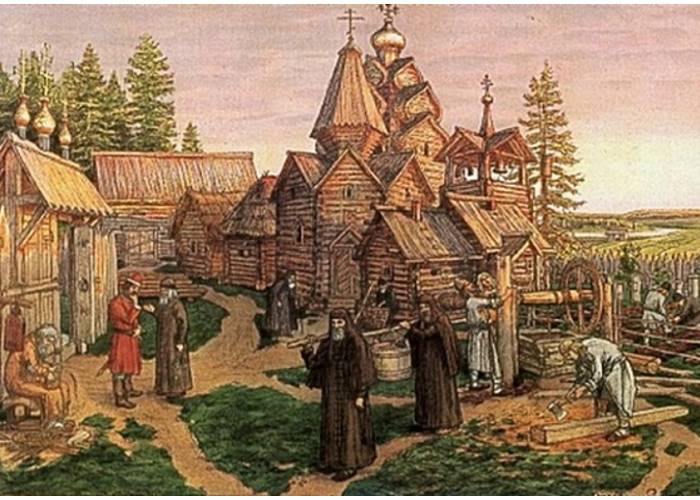

The Gulag camp system was first established on the Solovetsky Islands in 1923 and soon spread to the White Sea Coast, Karelia, the Urals, and the Kola Peninsula. As the number of prisoners grew, this population increasingly came to represent a “strategic workforce.” The White Sea Canal was the first “great construction project.” As many as 80,000 Gulag prisoners, men and women, young and old, spent 20 murderous months building a 180-kilometer canal, linking Lake Onega to the White Sea, using only spades, pickaxes, hatchets, and wheelbarrows. Ill-conceived and in the end of little strategic or economic use, the canal project presaged an even greater fiasco, the construction of the Trans-Arctic Railroad, which came to be known as “The Road of Death.” Began in 1947 on Stalin’s whim, construction was initiated on the sketchiest of plans. Stalin wanted a seaport at the mouth of the Enisei River. A seaport required the support of a railroad, so Stalin ordered one built to connect Salekhard and Igarka. Once again, using the most primitive of tools, 70,000 prisoners (new arrivals continually replaced the dead) laboured in indescribable conditions. They wasted away from malnourishment and 12-hour daily work shifts, in temperatures as low as minus 65 degrees Celsius, dressed in ragged clothing. Of the 900 kilometers of railroad built only a 190-km section was ever used. Hundreds of thousands died building it.

Conditions were just as brutal in the Kolyma camps (set up in the Butugychag mountain range). Established in 1932 to mine gold deposits in the upper and central parts of the Kolyma River, these were part of the biggest prison camp system in the USSR. The next largest network of camps was in Vorkuta, located 160 Kilometers above the Arctic Circle. There, at the foot of the Arctic Ural Mountains, 15 coal mines were surrounded by 150 camps, holding at all times, between 1931 and 1956, approximately 50,000 prisoners. In all of the camps, the daily death tolls from exposure, starvation, and prisoner abuse were staggering.

Who ended up in the camps? Initially, members of the Tsarist army, the clergy, and wealthy peasants. They were soon followed by the intelligentsia — writers, artists, and scientists. After WWII, there was a massive influx of nationalists, those who fought the Soviet invasion of their countries: men and women from Ukraine, the Baltic Republics, Poland, as well as Hungarians, Romanians, Czechs, Germans, and Japanese. Tragically, those who heroically fought the Nazis, and Soviet prisoners of war, accused of “betraying the fatherland,” also ended up in the camps.

A giant net was cast over Soviet Russia. It worked indiscriminately to condemn millions. During The Great Purge (1937-8), it netted even those who cast the net; the entire upper echelon of the dreaded NKVD was executed or sent to death in the labor camps.

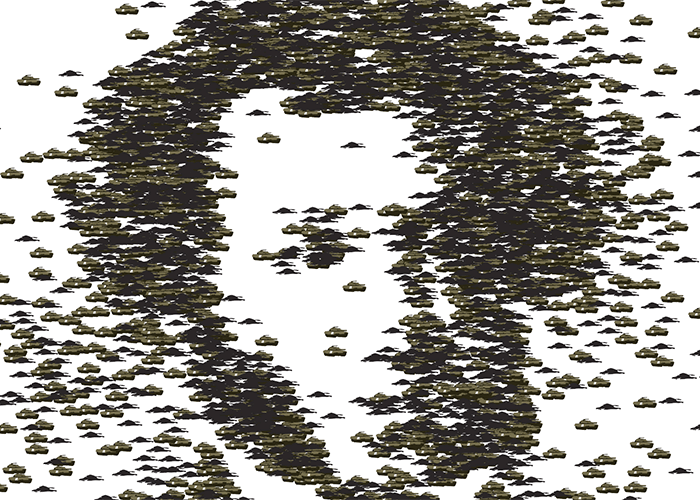

These photos remind us of the incalculable number of ruined lives, destroyed by the Communist experiment and a psychopathic dictator. The photos and testimonials of the survivors provide a profoundly disturbing but partial picture. There are many types of hell on earth. To know the full horror, you had to be there.

This book addresses a chasm in our understanding of Stalinist and Communist Russia. It’s an important document.