https://royallib.com/read/lure_samuil/uspehi_yasnovideniya.html#0

In the first thousand pages, the Unknown Author, disregarding entertainment value, repeatedly warned the main characters about upcoming events, explained His moral and creative principles in a form accessible to their understanding, and outlined the plan for the story He had conceived.

He introduced his extraordinary representatives into the narrative—characters who were inactive but had a very strong voice, as if reproducing the author’s direct speech. They commented on episodes that had already happened and outlined the content of the following chapters—and one of them was even entrusted with retelling the encrypted summary of the epilogue…

But the plan, it seems, became more complicated, the volume of the work increased dramatically, and the Author finally grew tired of teaching countless characters to read, even syllable by syllable, the text in which He had placed them. Let them forget their notorious reality, let them imagine themselves as co-authors of the dream, because it is so interesting for them to catch each other in the dark… After all, this is what is called freedom.

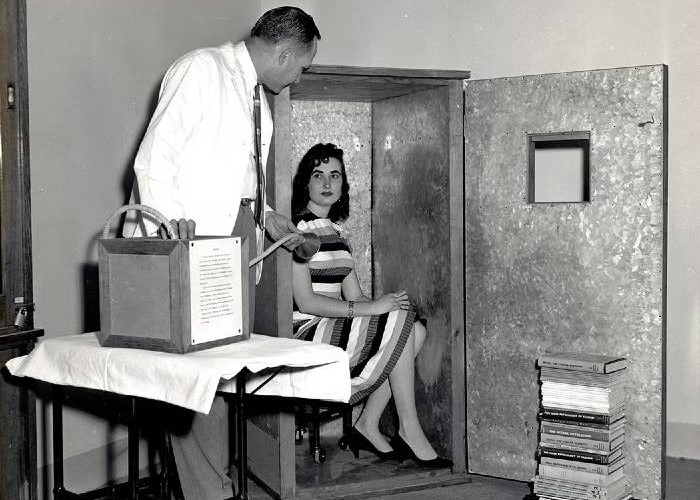

From time to time, some people venture to make individual attempts to predict the development of the plot. For example, a whole class of creatures and genres has formed to serve autobiographical curiosity: when a character expresses a willingness to go to any (reasonable) lengths — just tell me, magician, favorite of the gods, what will happen in my life. The metaphor received in response is attempted to be defused, like a mine, without understanding its mechanism, and the flash of insight coincides with the moment of explosion. Other subjects of so-called clairvoyance, such as what will happen to me afterwards and what will happen to others without me, are of little interest to most people. Seers and prophets who explore these topics are poorly paid and little believed; their conclusions are taken for fiction. It seems that the author, equally dissatisfied with their presumptuousness and our frivolity, deliberately presents them as somewhat ridiculous in the eyes of their contemporaries.

I. What is the afterlife like?

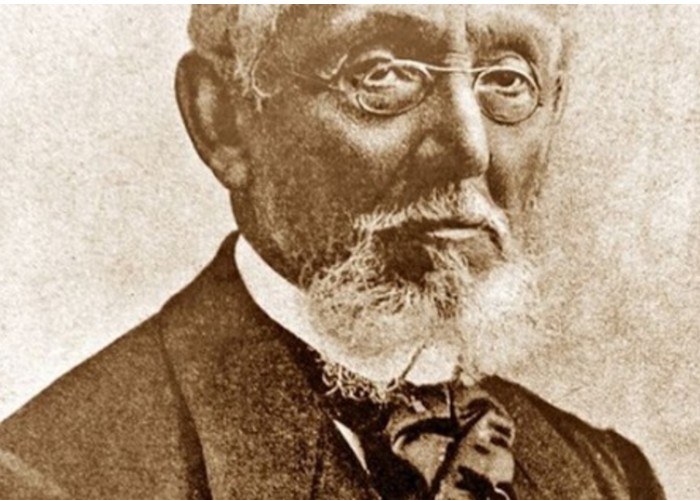

There is no doubt that Emanuel Swedenborg was a man of immense knowledge and extraordinary intelligence. After all, he was the first to establish that our Sun is one of the stars of the Milky Way, and that thoughts flash in the cortex of the large hemispheres of the brain – in the gray matter. He also predicted the day of his death—albeit not long before it happened, but accurately: March 29, 1772.

He was an exceptionally intelligent, truthful, serious, and conscientious representative of the Swedish nobility; among other things, he was an honorary member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

This is what happened to him in London in the fifty-eighth year of his life (1745). He was sitting in a tavern having lunch when suddenly fog filled the room, and various reptiles appeared on the floor. It became completely dark in the middle of the day. When the darkness dissipated, the reptiles were gone, and in the corner of the room stood a man radiating light. He said to Swedenborg in a threatening tone, “Don’t eat so much!” Swedenborg seemed to go blind for a few minutes, but when he came to, he hurried home. He did not sleep that night, did not touch food for a day, and the next night he saw that man again. Now the stranger was wearing a red robe; he said, “I am God, the Lord, the Creator and the Redeemer. I have chosen you to explain the inner and spiritual meaning of the Scriptures to people. I will dictate to you what you must write.”

The dictation lasted for many years and filled many volumes: it was a direct revelation — “the very one that is understood by the coming of the Lord,” as Swedenborg soon realized. Through him, the Creator explained to humanity for the last time the meaning of the Bible, the meaning of life, and also revealed the mystery of our afterlife. In order to make the text as clear and scientific as possible, Swedenborg was granted access to the afterlife—he visited paradise, inspected hell, interviewed angels and spirits; not content with the confessions of the dead, he himself experienced clinical death.

As a result, it turned out that “after the separation of the body from the spirit, which is called death, a person remains the same person and lives on”!

“A person, having turned into a spirit, does not notice any change, does not know that he has died, and considers himself to be in the same body as he was on earth… He sees as before, hears and speaks as before, perceives by smell, taste, and touch as before. He has the same inclinations, desires, and passions; he thinks, reflects, is moved or struck by something; he loves and desires as before; those who loved to study continue to read and write as before. He even retains his natural memory; he remembers everything he heard, saw, read, learned, and thought from his earliest childhood to the end of his earthly life…

Extremely encouraging news, isn’t it? Even too much so: only a computer could be poisoned by eternal memory, and few people need samizdat there… But we’ll see about that — and most importantly, no one will disappear. According to Swedenborg, it seems that we disappear only from view: not from space, but beyond the horizon—only from the point of view of others; and we lose not ourselves—not even our bodies—but only the roles we have played; we part, it is true, forever—a terrible word!—but with whom? With what? With the scenery of the play; and with the troupe, of course: farewell, farewell, actors and performers!

Under such conditions, death is no more frightening than divorce—or some kind of iron curtain: emigration to a new reality, and nothing more. If you love no one.

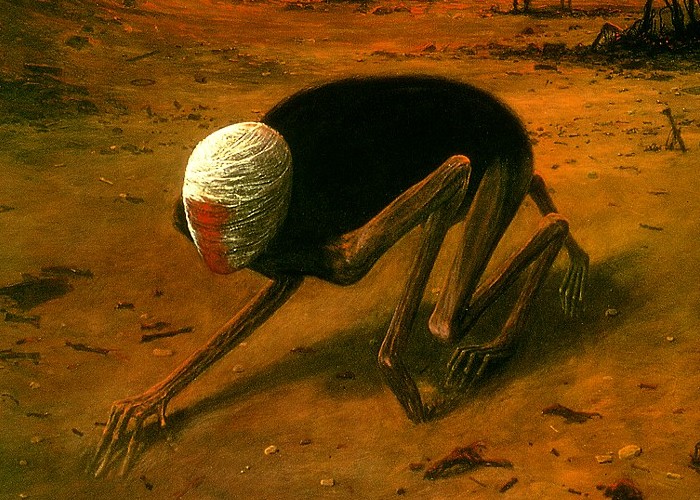

But that’s the point, and wait before you rejoice. Swedenborg asserts that everything remains “as before” only at first — usually for no longer than a year. During this time, the deceased person realizes — from conversations with other spirits, as well as in solitary reflection — what or whom he loved during his lifetime — and is completely transformed into the love that dominated him. And so, those who loved goodness and truth—that is, God and their neighbor—gradually become angels, smoothly ascending into heaven, where they lead a fascinating life that cannot be described here. And those who loved and continue to love evil and falsehood more than anything else in the world—namely, the material world and themselves—fly headlong into hell of their own accord, without anyone forcing them, in order to live among their own kind and enjoy themselves in their own way: these are devils.

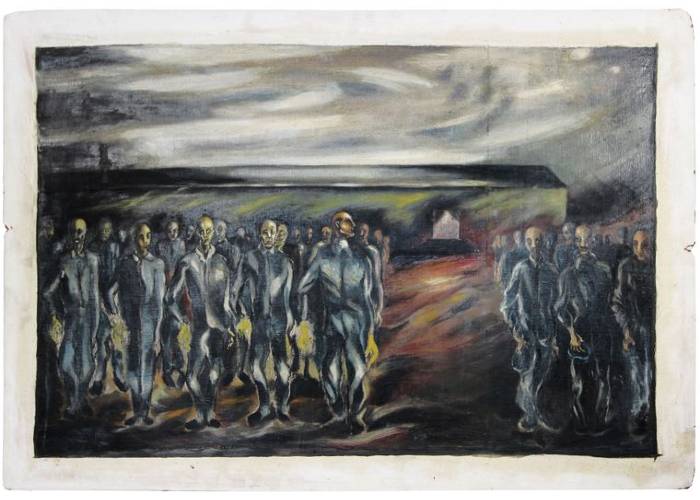

“…When a spirit arrives in hell of its own free will or enters there with complete freedom, it is first accepted as a friend and therefore confident that it is among friends, but this lasts only a few hours: meanwhile, they examine the extent of its cunning and strength. After that, they begin to attack him in various ways, gradually with greater force and cruelty. To do this, they lead him deeper and deeper into hell, for the deeper and deeper he goes, the more evil the spirits become. After the attacks, they begin to torture him with cruel punishments and do not stop until the unfortunate man becomes a slave. But since there are constant attempts at rebellion there, because everyone wants to be greater than the others and burns with hatred for them, new disturbances arise. Thus, one spectacle is replaced by another: those who have been enslaved are freed and help some new devil to take possession of others, while those who do not yield and do not obey the orders of the victor are again subjected to various torments, and so on and so forth…”

A strangely familiar picture, don’t you think? It should be added that Swedenborg understood before Kant how conventional ideas about time, space, and causes are. He is convinced—and assures us—that heaven is within each of us, yet riddled with many hells.

Thus, Swedenborg is not particularly comforting either. And how I would like, at the last moment, to have time to think that sooner or later I will see again someone with whom it is unbearable to part. According to Christian teaching, as we know, such a meeting can only take place at the end of time, after a global catastrophe—but will we find each other in a crowd of billions?

But if Swedenborg’s brilliant formula is correct—that a person is the embodiment of their love—then even if his other conjecture is incorrect—that after death, a person remains forever as they are by their own will and by the love that prevails in them—life is still not entirely meaningless.

As one of Swedenborg’s most attentive readers noted: “Is it necessary to sit in a basement wearing a shirt and hospital pants in order to consider oneself alive? That’s ridiculous!”

I don’t know if another reader, Clive Staples Lewis, is correct in deducing from the problem of personal immortality a moral choice between totalitarianism and democracy: “If a person lives only seventy years, then the state, or nation, or civilization, which can exist for a thousand years, is undoubtedly of greater value. But if Christianity is right, then the individual is not only more important, but incomparably more important, because he is eternal, and the life of a state or civilization is but a moment compared to his life.”

Personally, I still suspect that the universe is a totalitarian system. But this does not mean, in my opinion, that it is right to kill us. It is simply that it can do nothing else with those who have become the embodiment of its love.

II. Constantine’s Revelation

“But that Turgenev and Dostoevsky are above me is nonsense. Goncharov, perhaps. L. Tolstoy, undoubtedly. But Turgenev is not at all worthy of his reputation. To be above Turgenev is not much. It’s not a big claim…”

He did not receive a crumb of literary fame; Russia paid no attention to his fiction. And so, like an evil sorceress who was given a cake at a party in the royal castle, Konstantin Leontiev began to shout threatening predictions. They have partly come true, and it seems very likely that they will come true completely. He forced people to respect him—and he couldn’t have come up with anything better.

At the age of thirty-two, he became desperately, madly afraid of death—and that his soul would go to hell—and since then he has persistently begged the church to relieve him of his freedom: he knew too well the power of various temptations and imagined too clearly and vividly the torture of eternal fire.

Literary and everyday grievances and a premonition of horror sharpened his malicious insight. Leontiev was irritated by the high-minded talk of Turgenev and Nekrasov about some human rights and the suffering of the people. Leontiev had no doubt that he understood his homeland incomparably more deeply. He admired Russia for its contempt for freedom.

“The great experiment of egalitarian freedom,” Leontiev wrote in 1886, “has been tried everywhere; fortunately, we seem to have stopped halfway, and our ability to willingly submit to the stick (in both the direct and indirect sense) has not been completely lost, as it has in the West.”

Therefore, only Russia has the power to suspend history—that is, to delay the rapidly approaching end of the world. After all, only here has the masses not yet fragmented—and they live with the cherished dream of a powerful coercive body, the indestructible idea of statehood.

“No, morality is not the calling of the Russians! What morality can there be in a wayward, spineless, sloppy, lazy, and frivolous tribe? But statehood—yes, because here the stick, Siberia, the gallows, prison, fines, etc. are in effect.”

Moreover, Leontiev argued that it was a great stroke of luck for Russia that decent people were such a rarity there: this was the guarantee of its historical longevity and spiritual purity:

“… all these vile personal vices of ours are very useful in a cultural sense, for they give rise to the need for despotism, inequality, and various forms of discipline, both spiritual and physical; these vices make us ill-suited to the bourgeois-liberal civilization that still prevails in Europe.”

An analysis of the circumstances that had developed so happily convinced Leontiev that Russia was destined to revive the most colorful of ideals of social order—medieval, but only on the basis of the most advanced theory:

“Without the help of socialists, how can we talk about this? I am of the opinion that socialism in the 20th and 21st centuries will begin to play the role that Christianity played on the basis of religion and the state when it began to triumph.”

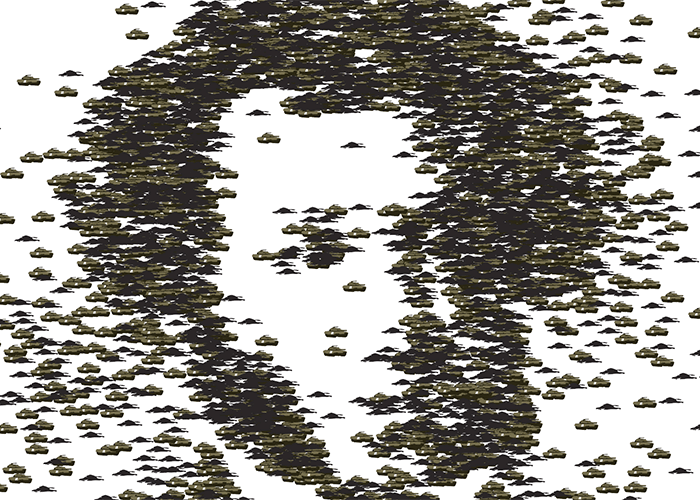

The foresight is striking, but that’s not all. Read on: on the same page of a private letter to an old acquaintance, the course of history is predicted so far in advance—and in such detail and with such accuracy—as no mortal has ever managed to do. Except perhaps Nostradamus—but try checking Nostradamus, while Leontiev’s prophecy has indeed come true, literally. So, March 15, 1889. The third volume of Capital has not yet been published. Alexander III reigns in Russia. Tolstoy writes Resurrection, Fet writes Evening Lights, Chekhov writes A Boring Story, and Saltykov drafts a newspaper announcement of his own death. Vladimir Ulyanov is 19 years old, Joseph Dzhugashvili is 10. No one knows the future, except for an unknown thinker living by the fence of the Optina Desert, in a separate house, on the second floor. Under his pen, the new master of destiny, the emperor of socialism, the savior of Russia, comes into being for the first time: the savior of Russia:

“Now socialism is still in the period of martyrs and first communities, scattered here and there. There will be a Constantine for it (it is very possible, and even most likely, that this economic Constantine will be called Alexander, Nikolai, Georgy, that is, in no case Louis, Napoleon, Wilhelm, Francis, James, or George…). What is now an extreme revolution will then become protection, an instrument of strict coercion, discipline, and even, in part, slavery…”

Brilliant intuition—but also brilliant logic: “Socialism is the feudalism of the future”!

The alternative is also depicted here: if socialism fails to put an end to liberalism and enslave the population of the planet— “either the final civil strife predicted by the Gospel will begin (I personally believe this); or, through careless and reckless use of chemistry and physics, people, carried away by an orgy of inventions and discoveries, will finally make such a colossal physical mistake that “the air will curl up like a scroll” and “they themselves will begin to perish by the thousands…”

This is also a highly plausible prediction, is it not? However, the Creator’s plan does not take probability theory into account and cannot be comprehended by reason alone. The final formula only dawns on Leontiev six months later. Listen, listen!

“My intuition tells me that the Slavic Orthodox tsar will one day take control of the socialist movement (just as Constantine of Byzantium took control of the religious movement) and, with the blessing of the Church, establish a socialist way of life in place of the bourgeois-liberal one. And this socialism will be a new and harsh triple slavery: to the communities, the Church, and the Tsar.”

The West is doomed, and Russia will triumph, turning into an unbreakable paradise of slaves. Know our people, you crybaby Chaadaev! “And the Grand Inquisitor will be allowed, rising from his coffin, to show his tongue to Fed. Mikh. Dostoevsky”

There remains a faint hope that Leontiev was wrong at least once, somewhere; that this demonic mind was blinded by unrequited love for Russian literature; that he would have gone beyond this disgusting utopia (is it a utopia?) if Turgenev had not written to Leontiev in 1876: “So-called fiction, it seems to me, is not your true calling…”

But if Leontiev was simply smarter than everyone else and guessed correctly — literature is canceled, and there is nothing to regret here on Earth.

…………………….

Самуил Лурье

Успехи ясновидения

(Трактаты для А.)

***

На первых тысячах страниц Неизвестный Автор, пренебрегая занимательностью, то и дело предуведомлял главных героев о предстоящих событиях, в доступной их пониманию форме излагал Свои моральные и творческие принципы, а также план замышленной истории.

Он ввел в повествование Своих чрезвычайных представителей – лиц бездействующих, но с очень сильным слогом, как бы воспроизводящим прямую Авторскую речь. Они комментировали эпизоды, оставшиеся позади, намечали содержание следующих глав, – и одному из них даже было доверено пересказать зашифрованный конспект эпилога…

Но замысел, надо полагать, усложнился, объем творения необычайно возрос, и Автору наконец надоело обучать бесчисленных персонажей хоть по складам читать текст, в котором Он их поселил. Пусть забудутся этой своей пресловутой реальностью, пусть воображают себя соавторами сна, ведь им так интересно ловить друг дружку в темноте… Ведь именно это называют свободой.

Кое-кто время от времени отваживается на индивидуальную попытку предугадать развитие сюжета. Образовался, например, целый разряд существ и жанров, – обслуживающих автобиографическое любопытство: когда персонаж выражает готовность пойти на любые (в пределах разумного) издержки – только скажи мне, кудесник, любимец богов, что сбудется в жизни со мною. Полученную в ответ метафору пробуют обезвредить, как мину – не постигая устройства, – и вспышка разгадки совпадает с моментом взрыва. Другие предметы так называемого ясновидения: что сбудется со мною после и что будет с остальными без меня занимают далеко не всех. Провидцам и прорицателям, разрабатывающим эти темы, плохо платят и мало верят, их выводы принимают за вымыслы. Кажется, что Автор, одинаково недовольный их самонадеянностью и нашим легкомыслием, нарочно представляет их немного смешными в глазах современников.

I. Какова загробная жизнь

Не приходится сомневаться, что Эмануэль Сведенборг был человек необъятных познаний, к тому же необыкновенно умный. Ведь это он первый установил, что наше Солнце – одна из звезд Млечного Пути, а мысли вспыхивают в коре больших полушарий мозга – в сером веществе. И он предсказал день своей смерти – пусть незадолго до нее, но точно: 29 марта 1772.

Исключительно толковый, правдивый, серьезный, добросовестный представитель шведской знати; почетный член, между прочим, Петербургской АН.

Вот что с ним случилось в Лондоне на пятьдесят восьмом году жизни (1745). Он сидел в таверне за обедом, как вдруг туман заполнил комнату, а на полу обнаружились разные пресмыкающиеся. Тут стало совсем темно средь бела дня. Когда мрак рассеялся – гадов как не бывало, а в углу комнаты стоял человек, излучавший сияние. Он сказал Сведенборгу грозно: “Не ешь так много!” – и Сведенборг вроде как ослеп на несколько минут, а придя в себя, поспешил домой. Он не спал в эту ночь, сутки не притрагивался к еде, а следующей ночью опять увидел того человека. Теперь незнакомец был в красной мантии; он произнес: “Я Бог, Господь, Творец и Искупитель. Я избрал тебя, чтобы растолковать людям внутренний и духовный смысл Писаний. Я буду диктовать тебе то, что ты должен писать”.

Диктант растянулся на много лет и томов: это было непосредственное Откровение – “то самое, которое разумеется под пришествием Господа”, как понял вскоре Сведенборг. При его посредстве Создатель в последний раз объяснял человечеству смысл Библии, смысл жизни, а также раскрыл тайну нашей посмертной судьбы. Чтобы текст получился как можно более отчетливым высоконаучным, Сведенборг получил допуск в загробный мир – побывал в раю, осмотрел ад, интервьюировал ангелов и духов; не довольствуясь признаниями умерших, сам отведал клинической смерти.

В результате оказалось, что “по отрешении тела от духа, что называется смертью, человек остается тем же человеком и живет”!

“Человек, обратясь в духа, не замечает никакой перемены, не знает, что он скончался, и считает себя все в том же теле, в каком был на земле… Он видит, как прежде, слышит и говорит, как прежде, познает обонянием, вкусом и осязанием, как прежде. У него такие же наклонности, желания, страсти, он думает, размышляет, бывает чем-то затронут или поражен, он любит и хочет, как прежде; кто любил заниматься ученостью, читает и пишет по-прежнему… При нем остается даже природная память его, он помнит все, что, живя на земле, слышал, видел, читал, чему учился, что думал с первого детства своего до конца земной жизни…”

Чрезвычайно отрадное известие, не правда ли? Даже и слишком: вечной собственной памятью не отравится разве компьютер – и мало кому нужен тамошний самиздат… Но это мы еще посмотрим – а главное, главное: никто не исчезнет. По Сведенборгу выходит, будто исчезаем мы – просто из виду: не из пространства, но за горизонтом – всего лишь с точки зрения других; и теряем не себя – даже и не тело – а только сыгранную роль; расстаемся, правда, навсегда – слово ужасное! – но с кем? с чем? – с декорацией пьесы; ну, и с труппой, разумеется: прощайте, прощайте, действующие лица и исполнители!

При таких условиях смерть не страшней развода – или какого-нибудь железного занавеса: эмиграция в новую действительность, и больше ничего. Если никого не любить.

Но в том-то и дело, и погодите ликовать. Сведенборг утверждает, что все остается “как прежде” только на первых порах – обычно не дольше года. За это время умерший человек уясняет – из бесед с другими духами, а также в уединенных размышлениях: что или кого любил он при жизни – и весь преображается в ту любовь, которая над ним господствовала. И вот, те, кто любил благо и истину – то есть Бога и ближнего, – те потихоньку становятся ангелами, плавно погружаются в небеса и там ведут увлекательную жизнь, здесь непересказуемую. А кто любил и продолжает любить больше всего на свете зло и ложь – а именно материальный мир и самого себя, – такие без чьего-либо принуждения, по собственному горячему желанию летят вверх тормашками в ад, чтобы жить среди своих и наслаждаться на свой собственный лад: это дьяволы.

“…Когда дух по доброй воле своей или с полной свободой прибывает в свой ад или входит туда, он сначала принят как друг и потому уверен, что находится между друзей, но это продолжается всего несколько часов: меж тем рассматривают, в какой степени он хитер и силен. После того начинают нападать на него, что совершается различным образом, и постепенно с большей силой и жестокостью. Для этого его заводят внутрь и вглубь ада, ибо чем далее внутрь и вглубь, тем духи злее. После нападений начинают мучить его жестокими наказаниями и не оставляют до тех пор, покуда несчастный не станет рабом. Но так как там попытки к восстанию беспрестанны, вследствие того что каждый хочет быть больше других и пылает к ним ненавистью, то возникают новые возмущения. Таким образом, одно зрелище сменяется другим: обращенные в рабство освобождаются и помогают какому-нибудь новому дьяволу завладеть другими, а те, которые не поддаются и не слушаются приказаний победителя, снова подвергаются разным мучениям, – и так далее постоянно…”

Странно знакомая картинка, вы не находите? Необходимо добавить, что Сведенборг раньше Канта понял, насколько условны обычные представления о времени, пространстве и причинах. Он уверен – и уверяет, – будто небеса находятся внутри каждого из нас – и притом изрыты множеством адов.

Таким образом, и Сведенборг не особенно утешает. А как хотелось бы в последний момент – успеть подумать, что рано или поздно еще увидишься с кем-нибудь, с кем невыносимо разлучиться. По учению христианской церкви, как известно, такая встреча может состояться лишь в конце времен, после глобальной катастрофы – да еще найдем ли, узнаем ли друг друга в многомиллиардной толпе?

Но если верна гениальная формула Сведенборга: человек есть олицетворение своей любви, – то даже если неверна другая его догадка: будто человек после смерти навеки пребывает таким, каков он есть по воле своей и по господствующей в нем любви, – жизнь все-таки бессмысленна не вполне.

Как заметил один из внимательнейших читателей Сведенборга: “Разве для того, чтобы считать себя живым, нужно непременно сидеть в подвале, имея на себе рубашку и больничные кальсоны? Это смешно!”

Не знаю, корректно ли другой читатель – Клайв Стейплз Льюис – выводит из проблемы личного бессмертия моральный выбор между тоталитаризмом и демократией: “Если человек живет только семьдесят лет, тогда государство, или нация, или цивилизация, которые могут просуществовать тысячу лет, безусловно, представляют большую ценность. Но если право христианство, то индивидуум не только важнее, а несравненно важнее, потому что он вечен и жизнь государства или цивилизации – лишь миг по сравнению с его жизнью”.

Лично я все-таки подозреваю, что Вселенная – тоталитарная система. Но из этого не следует, по-моему, что, убивая нас, она права. Просто она больше ничего не способна сделать с теми, кто стал олицетворением своей любви.

II. Откровение Константина

“Но что Тургенев и Достоевский выше меня, это вздор. Гончаров, пожалуй. Л. Толстой, несомненно. А Тургенев вовсе не стоит своей репутации. Быть выше Тургенева – это еще немного. Не велика претензия…”

Ни крошки литературной славы ему не досталось, Россия не обратила внимания на его беллетристику. И вот – совсем как злая волшебница, которую на празднике в королевском замке обнесли пирожным, – Константин Леонтьев стал выкрикивать угрожающие предсказания. Они отчасти сбылись, и очень похоже, что сбудутся полностью. Он уважать себя заставил – и лучше выдумать не мог.

Тридцати двух лет он отчаянно, до безумия, испугался смерти – и что душа пойдет в ад, – с тех пор неотступно умолял церковь избавить его от свободы: слишком хорошо знал силу разных соблазнов, слишком отчетливо и ярко воображал пытку вечным огнем.

Литературные и житейские обиды и предчувствие ужаса изощрили в нем злорадную проницательность. Леонтьева раздражали прекраснодушные толки Тургеневых, Некрасовых о каких-то там правах человека и страданиях народа. Леонтьев не сомневался, что понимает отчизну несравненно глубже. Он восхищался Россией за то, что свободу она презирает.

“Великий опыт эгалитарной свободы, – писал Леонтьев в 1886 году, сделан везде; к счастью, мы, кажется, остановилась на полдороге, и способность охотно подчиняться палке (в прямом и косвенном смысле) не утратилась у нас вполне, как на Западе”.

Поэтому только России под силу приостановить историю – то есть оттянуть приближающийся стремительно конец света. Ведь только здесь масса еще не раздробилась – и живет заветной мечтой о могучем органе принуждения, неизбывной идеей государственности.

“Нет, не мораль призвание русских! Какая может быть мораль у беспутного, бесхарактерного, неаккуратного, ленивого и легкомысленного племени? А государственность – да, ибо тут действует палка, Сибирь, виселица, тюрьма, штрафы и т. д.”

Притом огромная удача для России, утверждал Леонтьев, что в ней порядочные люди – такая редкость: это залог ее исторического долголетия и духовной чистоты:

“…все эти мерзкие личные пороки наши очень полезны в культурном смысле, ибо они вызывают потребность деспотизма, неравноправности и разной дисциплины, духовной и физической; эти пороки делают нас малоспособными к той буржуазно-либеральной цивилизации, которая до сих пор еще держится в Европе”.

Анализ обстоятельств, сложившихся столь счастливо, убедил Леонтьева, что именно России суждено возродить самый красочный из идеалов общественного устройства – средневековый, но не иначе как на основе самой передовой теории:

“Без помощи социалистов как об этом говорить? Я того мнения, что социализм в XX и XXI веке начнет на почве государственно-экономической играть ту роль, которую играло христианство на почве религиозно-государственной тогда, когда оно начинало торжествовать”.

Предвидение поразительное, но это еще не все. Почитайте дальше: на этой же странице частного письма к старинному знакомцу ход истории предугадан так надолго вперед – и так подробно, и так безошибочно, – как не удавалось никому из смертных. Кроме разве что Нострадамуса – да только Нострадамуса попробуйте проверьте, а пророчество Леонтьева исполнилось действительно и буквально. Итак – 15 марта 1889 года. Третий том “Капитала” еще не издан. В России царствует Александр III. Толстой пишет “Воскресение”, Фет – “Вечерние огни”, Чехов – “Скучную историю”, Салтыков проект газетного объявления о своей кончине. Владимиру Ульянову 19 лет, Иосифу Джугашвили – 10. Будущего не знает никто, за исключением безвестного мыслителя, проживающего у ограды Оптиной пустыни, в отдельном домике, на втором этаже. Под его пером впервые обретает бытие новый властелин судьбы император социализма, спаситель России:

“Теперь социализм еще находится в периоде мучеников и первых общин, там и сям разбросанных. Найдется и для него свой Константин (очень может быть, и даже всего вероятнее, что этого экономического Константина будут звать Александр, Николай, Георгий, то есть ни в каком случае не Людовик, не Наполеон, не Вильгельм, не Франциск, не Джемс, не Георг…). То, что теперь крайняя революция, станет тогда охранением, орудием строгого принуждения, дисциплиной, отчасти даже и рабством…”

Гениальная интуиция – но и логика гениальная: “Социализм есть феодализм будущего”!

Тут же изображена и альтернатива: если социализму не удастся покончить с либерализмом и поработить население планеты – “или начнутся последние междуусобия, предсказанные Евангелием (я лично в это верю); или от неосторожного и смелого обращения с химией и физикой люди, увлеченные оргией изобретений и открытий, сделают наконец такую исполинскую физическую ошибку, что и “воздух, как свиток, совьется”, и “сами они начнут гибнуть тысячами”…”

Тоже в высшей степени правдоподобный прогноз, не так ли? Но предначертание Творца не считается с теорией вероятности – и постигается все-таки не рассудком; окончательная формула осеняет Леонтьева только через полгода, – слушайте, слушайте!

“Чувство мое пророчит мне, что славянский православный царь возьмет когда-нибудь в руки социалистическое движение (так, как Константин Византийский взял в руки движение религиозное) и с благословения Церкви учредит социалистическую форму жизни на место буржуазно-либеральной. И будет этот социализм новым и суровым трояким рабством: общинам, Церкви и Царю”.

Запад обречен – а Россия восторжествует, превратившись в нерушимый рай рабов. Знай наших, плакса Чаадаев! “И Великому Инквизитору позволительно будет, вставши из гроба, показать тогда язык Фед. Мих. Достоевскому”…

Остается слабая надежда, что Леонтьев хоть раз, хоть где-нибудь ошибся; что этот демонический ум ослепила безответная любовь к русской литературе; что он пошел бы дальше этой отвратительной утопии (утопии ли?), не напиши Леонтьеву Тургенев в 1876 году: “Так называемая беллетристика, мне кажется, не есть настоящее Ваше призвание…”

Но если Леонтьев просто был умнее всех и угадал верно – литература отменяется, и вообще не о чем жалеть здесь, на Земле.