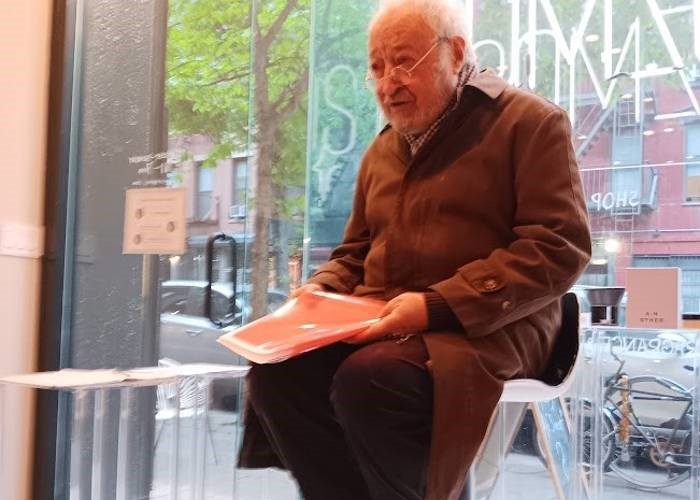

Birth

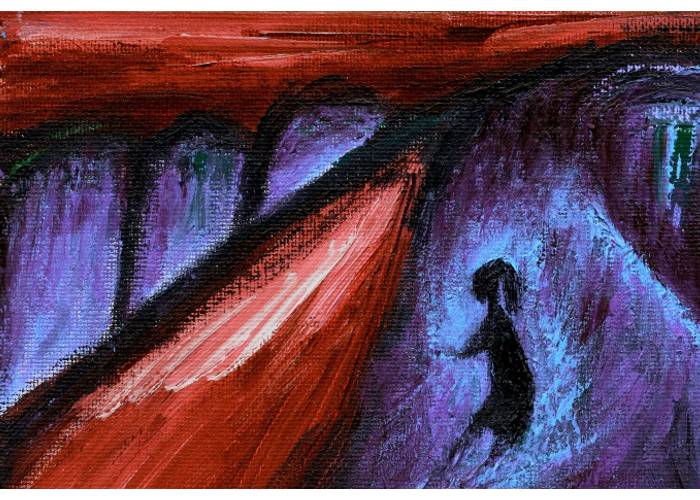

I was born in a lapse of time, my hand clinging to a dandelion, my feet gripping a vine leaf, my nose on my back, an eye on my ankle. The moon cast its dead pale rays, sprinkling the mortals’ dreams with a layer of spice. My mother wasn’t present at my birth or maybe she was there and her pain of being torn apart still throbs in my veins.

The nose on my back is reflected in a strange way in the eye on my ankle.

Naissance

Je suis née en un laps de temps, la main accrochée à un pissenlit, les pieds agrippés à une feuille de vigne, le nez dans le dos, l’oeil à la cheville. La lune dardait ses rayons de morte pâle, saupoudrant les rêves des mortels d’une couche épicée. Ma mère n’était pas présente à ma naissance, ou peut-être était-elle là et sa douleur d’être déchiré bat aujourd’hui encore dans mes veines.

Le nez de mon dos se reflète bizarrement dans l’oeil de ma cheville.

Рождение

Я родилась в прорехе времени, моя рука, уцепившаяся за одуванчик, мои ноги, захватившие линоя рука, уцепившаяся за одуванчик, мои ноги, захватившие линодолайка, линогыойк одуванчик, мои ноги, захватившие линодоланк, линодоланк линогыой Луна отбрасывала мертвые бледные лучи, посыпая пряностью сны смертных. Моя мать не присутствовала при моем рождении. Хотя, возможно, она там была, и боль, которую она, растерзанная, чувствовала, продолжает пувихисир.

Нос на моей спине странно отражается в глазу на моей лoдыжке.

* * *

First line

I wish I could write a first line that belonged to no one and would be the exact opposite of the desire to write that gave birth to it. A deadly, frozen breath would blow through its bowels, sealing with a burning touch each word’s face and imprinting on it the grimace of a newborn who comes into daylight as if into darkness. All the terror of what is dragged into being will explode in these faces, which will then recede, terrified by the vertigo of being, like a snail’s fearful horns. I will be all at once the snail’s horn, the hand reaching toward it and the newborn stopped half-way in the mother’s womb. I will also be the mother’s body, dead at the moment when the newborn meets the first ray of light.

Première ligne

Je voudrais écrire une première ligne qui n’appartienne à personne et qui soit tout le contraire du désir d’écrire qui l’a fait naître. Un souffle de mort lui traversera les entrailles, et la brûlure de ce souffle glacé imprimera sur le visage de chaque mot la grimace d’un nouveau-né venu au jour comme on va vers la nuit. Toute la terreur de ce qui est poussé à être explosera sur ces visages, qui se retireront ensuite, terrifiés par le vertige d’être, comme les cornes d’un escargot avant même qu’on les touche. Je serai à la fois, la corne de l’escargot, la main tendue vers elle et le nouveau-né arrêté en mi-chemin dans le corps de la mère. Je serai également le corps de la mère, mort au moment où le nouveau-né rencontrera le premier rayon de lumière.

Первая строка

Если бы я могла написать первую строку, которая бы никому не принадлежалa и которая была бы полной противоположностью давшему ей рождение желанию писать. Смертельное, леденящее дыхание пронизывало бы её изнутри, обжигающим прикосновением оставляя на лице каждого слова выражение новорожденного, встречающего свет дня, как тьму. Весь ужас того, что втянуто в бытие взорвется на их лицах, и они отступят, устрашенные головокружением бытия, как пугливые рога улитки. Я буду всем: и рогами улитки, и рукой, тянущейся к ним, и младенцем, остановившимся на полпути из материнской утробы. И я буду телом матери, умирающим в тот самый момент, когда младенец встречает первый луч света.

* * *

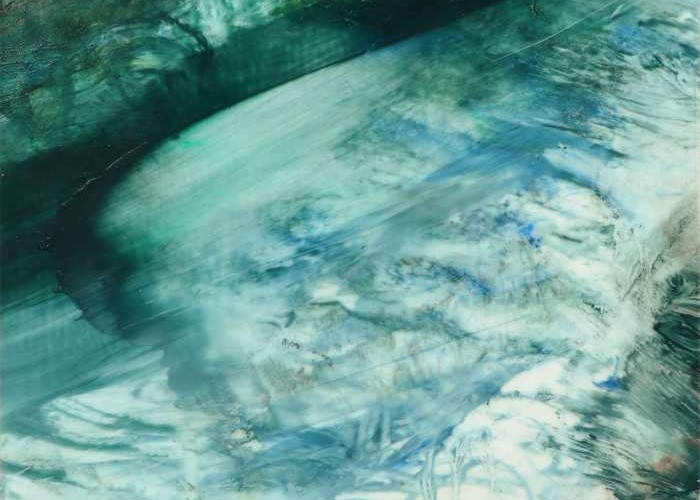

Voice of ice

I speak from inside the stem of a flower, a long green flower, and with each word a dewy pearl falls from the flower, which at night becomes an enormous eye brimming with tears. But the eye doesn’t cry. It waits, at the edge of tears. Somewhere in the universe of tears an ice wind blows on them and they freeze, they are now ice flowers, and I speak from inside the stem of an ice flower, and the flower no longer cries. I speak from inside the stem of an ice flower that has frozen inside my eye, and I can no longer leave my eye, can leave no longer.

Voix de glace

Je parle de l’intérieur d’une tige de fleur, verte et longue, longue et verte, et à chaque mot, une perle de rosée tombe de la fleur qui pendant la nuit devient un oeil immense noyé de larmes. Mais l’oeil ne pleure pas. Il attend, aux bords des larmes. Quelque part, dans l’univers des larmes, un vent glacé souffle sur elles, et elles gèlent, elles sont maintenant des fleurs de glace, et je parle de l’intérieur d’une tige de fleur de glace, et la fleur ne pleure plus. Je parle de l’intérieur d’une tige de fleur de glace qui a gelé dans mon oeil, et je ne peux plus sortir de mon oeil, je ne peux plus sortir.

Голос льда

Я говорю изнутри стебля цветка, длинного зеленого цветка, и с каждым словом из цветка падает капля перламутровой росы — в ночи он становится громадным глазом, наполненным слезами. Но глаз не плачет. Он ждет, замерев на краю слез. Где-то во вселенной слез ледяной ветер обдувает их и они замерзают, они стали ледяными цветами, и я говорю изнутри стебля ледяного цветка, и цветок больше не плачет. Я говорю из стебля ледяного цветка, который застыл внутри моего глаза, и я не могу больше покинуть свой глаз, больше не могу его покинуть.

* * *

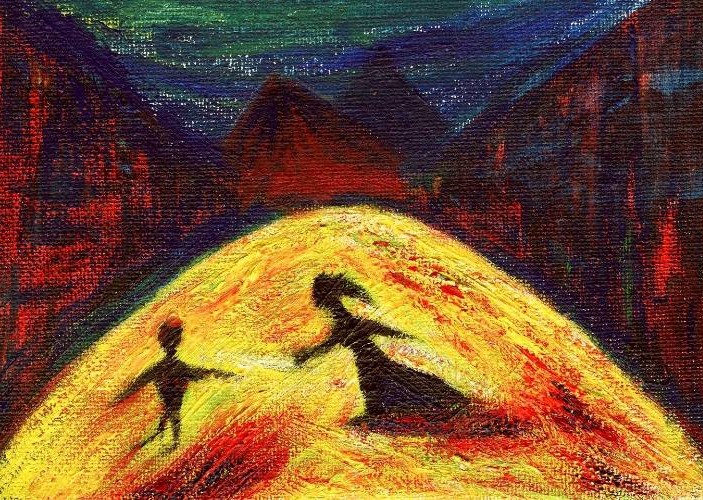

Bones without a body

My limbs are falling one by one. First one arm, then the other. My eyes are falling one by one. One eye, the other eye. My hair is falling bit by bit. From a distance, I watch my body shedding its leaves like a tree. Someone says: “You won’t get anywhere.” And my bones answer with a glassy jingling, and they are walking away bodyless, leaving the stripped flesh behind. From a distance, I watch the grinning face, which isn’t mine. And I’m dragging the bones the wind blows through, and my bones are singing like a happy cadaver. And in the end I’m where I started. Nowhere.

Os sans corps

Mes membres tombent un par un. D’abord un bras, ensuite l’autre. Mes yeux tombent un par un. Un oeil, l’autre oeil. Mes cheveux tombent un par un. Du dehors, je regarde mon corps qui se défeuille comme un arbre. Quelqu’un dit : “Tu n’arriveras nulle part.” Et mes os répondent par un cliquetis de verre, et ils marchent sans corps, laissant la chair épluchée derrière. Du dehors, je regarde la grimace sur le visage qui n’est pas le mien. Et je traîne après moi les os parmi lesquels souffle le vent, et mes os chantent comme un mort joyeux. Et à la fin je suis toujours au départ. Nulle part.

Кости без тела

Мои конечности отваливаются одна за другой. Сначала одна рука, потом другая. Мои глаза вываливаются из глазниц один за другим. Один глаз, другой глаз. Мои волосы выпадают, клок за клоком. Я наблюдаю свое тело со стороны как дерево, сбрасывающее листву. Кто-то мне говорит: “Никуда не денешься”. И мои кости позвякивают в ответ, и уходят бестелые, оставляя раздетую плоть позади. Со стороны я наблюдаю за усмехающимся лицом, которое мне уже не принадлежит. И я тащу свои кости, сквозь них дует ветер, а кости поют, как счастливый труп. И в конце концов я оказываюсь там, откуда я началась. Нигде.

* * *

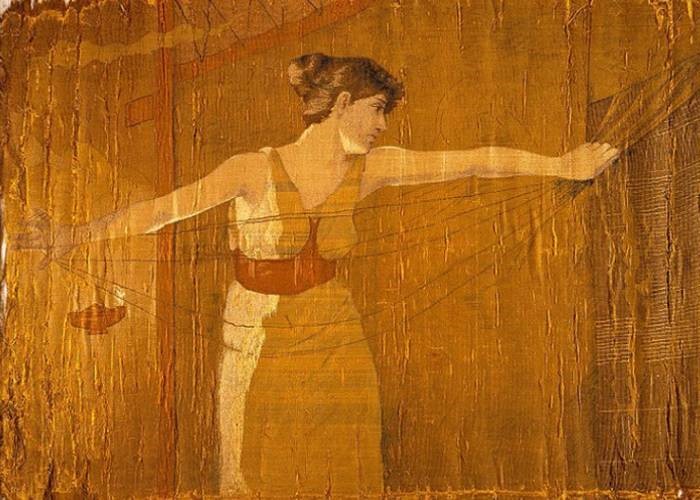

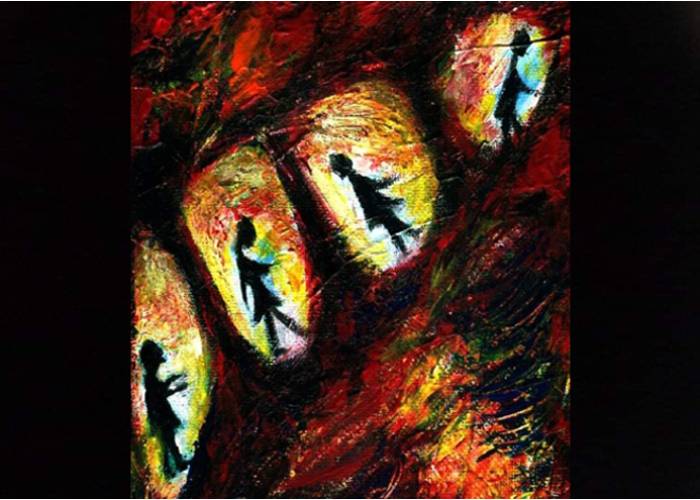

The woman who wasn’t and the voice of salt

Once there was a woman, who, whatever she did, could not be. In the morning she opened her eyes on an empty world carried into the sky by white doves, a world where she wasn’t. She wanted to show that she was, so she opened notebooks and books and she began to trace signs, but in the end only the notebooks were there. Around her, all kinds of things busied themselves with being: tomatoes, shoes, clothes lying around, even a computer. But she, no, she wasn’t. In the afternoons she sat on a deck chair and watched through the climbing kiwi vines the foamy waves of the ocean, listening to the sounds like faraway voices breaking on the rocks. Sea lions or sirens? Her eyes moistened in sympathy with the ocean of blue mist. And she tried once more to show that she was and opened her mouth to talk, but the words stopped in her throat, walled up. And out of her mouth grains of salt began flowing, piling up all around her body. And the pile grew higher and higher—it covered her hips, her belly, her breasts, her mouth, her eyes. In the end, only a shape vaguely resembling her was left, all salt.

La femme qui n’etait pas et la voix de sel

Il y avait une fois une femme qui, quoi qu’elle fît, ne pouvait être. Le matin, ses yeux scrutaient un monde vide emporté aux nues par des colombes blanches, un monde où elle n’était pas. Elle voulait montrer qu’elle était, alors elle ouvrait des cahiers et des livres et elle se mettait à tracer des signes, mais à la fin il n’y avait que les cahiers qui étaient là. Autour d’elle, toutes sortes de choses s’empressaient à être : tomates, chaussures, vêtements traînant par terre, même un ordinateur. Mais elle non, elle n’était pas. L’après-midi elle s’asseyait sur une chaise-longue et regardait, par la brèche taillée dans le feuillage de kiwi, les vagues écumeuses de l’océan, en écoutant les sons tels des voix lointaines qui se brisaient sur la grève rocheuse. Lions de mer ou sirènes? Ses yeux se voilaient en sympathie avec l’océan de brume bleue. Et elle tâchait encore une fois de montrer qu’elle était et ouvrait la bouche pour parler, mais les mots s’arrêtaient dans sa gorge, emmurés. Et de sa bouche commençaient à couler des grains de sel qui s’empilaient tout autour de son corps. Et le tas montait et montait, il couvrait ses hanches, son ventre, ses seins, sa bouche, ses yeux. À la fin, il ne resta d’elle qu’une forme qui lui ressemblait vaguement, toute en sel.

Женщина, которой не было, и голос соли.

Жила-была женщина. Что бы она ни делала, она никак не могла быть. Утром она открывала глаза и смотрела на пустой мир, унесённый в небо белыми голубями, мир, в котором она не была. Она хотела показать себе, что она есть и для этого она открывала тетради и книги и следила за знаками, но когда она заканчивала, оставались только тетради. Самые разные вещи вокруг неё насыщали себя бытием: помидоры, обувь, одежда, даже компьютер. Но её нет, её не было. Днем она сидела в шезлонге среди лиан киви и смотрела на пенистые волны океана, прислушиваясь к звукам, напоминающим разбивающиеся о скалы отдаленные голоса. Морские львы или сирены? Ее глаза увлажнились в сочувствии к океану печально-синего тумана. И она снова пробовала показать, что она есть, и открыла рот, чтобы говорить, но слова, как замурованные, застряли у нее в горле. И из ее рта потекли, рассыпаясь по всему телу, крупицы соли. Наслоения соли становились все выше и вышe, они покрыли ее бедра, ее живот, ее грудь, ее рот, ее глаза. Пока не остался лишь смутно напоминающий о ней силуэт, весь состоящий из соли.

English and French texts are the author’s; Russian translation is by Ekaterina Belousova.

English and French texts are from “Voice of Ice” / “Voix de Glace” by Alta Ifland (Les Figues Press, LA)