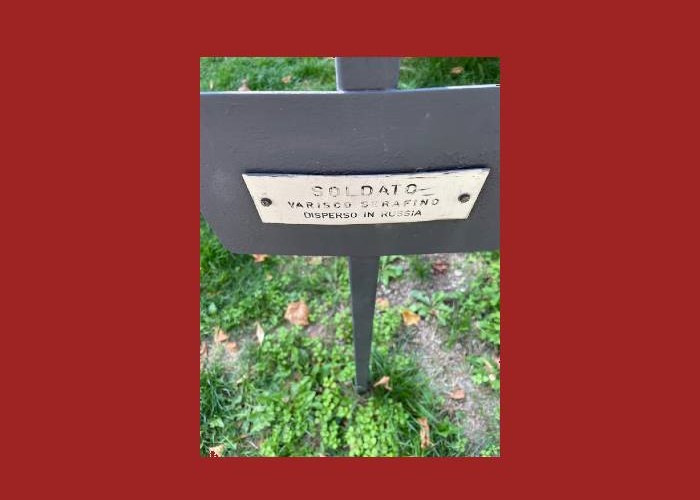

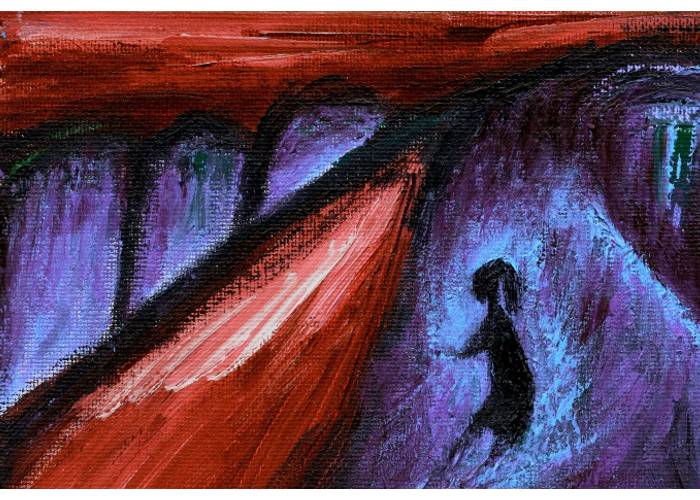

There Gumilev was lost, pulled asunder

by a bullet, and the lawn drank his blood by the dram.

There sound the lutes, the distant thunder.

Who else managed to catch that tram?

Here goddaughter Natalia sighs

(gazing ahead as the dead might do)

The Mariupol trams could really fly

Back when they were shiny and new.

They imported them from somewhere in Europe:

with wi-fi, timetables and ads on TV,

with windows so bright, and the seats a delight.

Where could my brother and mother be?

Ten days and no word, they’ve been too quiet.

In the news the rails lie in tatters.

I answer: you know, as luck would have it

I know of this tram; I’ve read all about it.

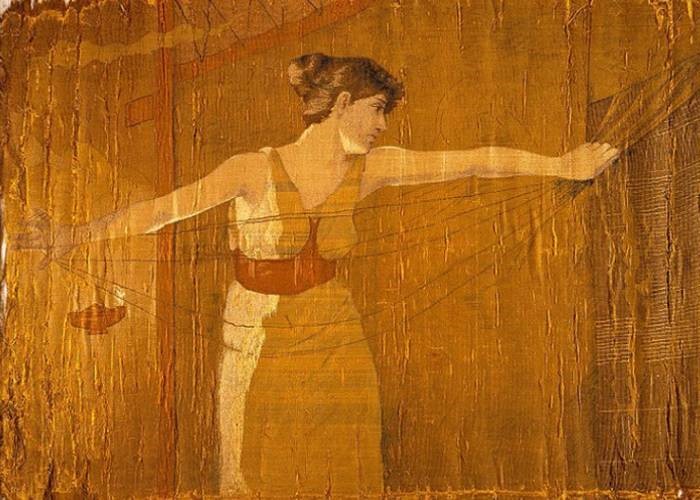

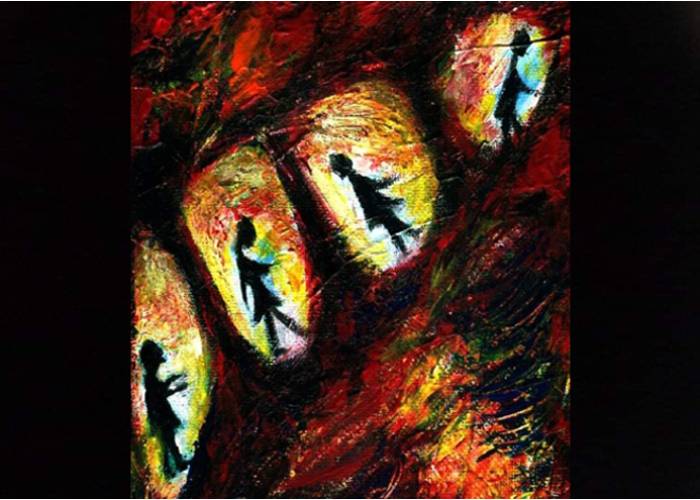

The tram runs its route, but makes no stops,

despite the passengers’ pleas to climb off.

The car and the rails shine new as they drive.

They all watch the ads, and in this are alive.

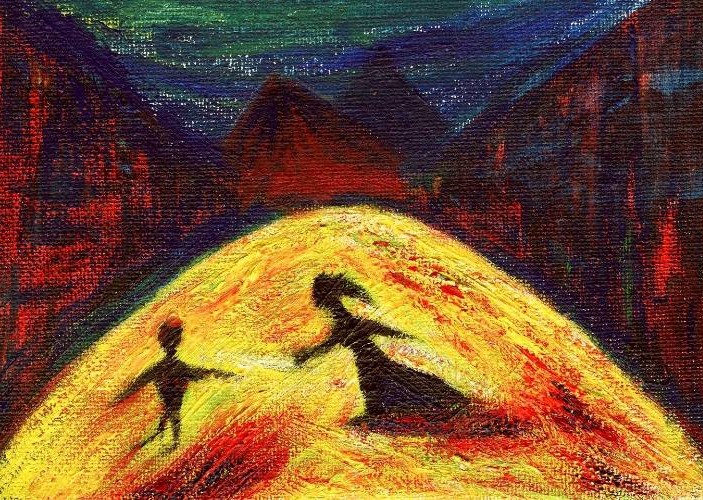

He’s right on track, his course well defined.

The tram driver is knowing and able:

to the India of the spirit, the Auschwitz of the mind

each station and stop is timed in his table.

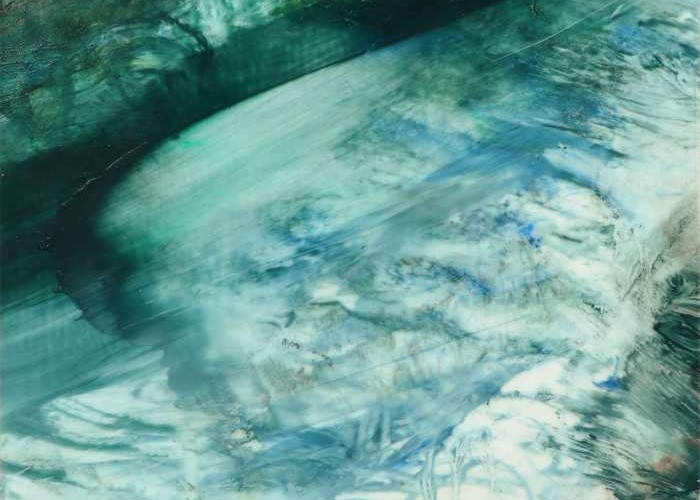

Below, the city of Mary remains

little seaside Mariupol, forlorn.

Mashenka, there they invoked your name –

Lay down your arms! – in their dark bullhorn.

Мариупольский трамвай

Там Гумилев заблудился, влекомый

пулей, и кровь его пьет трава.

Там звоны лютни, дальние громы.

Кто успел запрыгнуть в трамвай?

Вот говорит мне кума Наталья

(смотрит вперед будто неживая)

У нас в Мариуполе прям летали

раньше новехонькие трамваи.

Их привезли из Европы откуда-то:

табло, телевизор, вай фай с рекламой,

окна огромные, сиденья чудные.

Как узнать, что с братом и мамой?

Десять дней ничего не слышно.

А в новостях рельсы жгутами.

Я отвечаю: знаешь, так вышло

Что я о трамвае этом читала.

Он ходит, только без остановок,

хоть выйти просятся пассажиры.

Он правда новый, и рельсы новые.

Все смотрят рекламу, и все в нем живы.

Он не заблудился, маршрут исчислил.

Вагоновожатый – он малый ловкий:

до Индии духа, Освенцима мысли

расставил заправки и остановки.

Внизу остался город Марии,

приморский маленький Мариуполь.

Машенька, там о тебе говорили –

Бросьте оружие – в черный рупор.