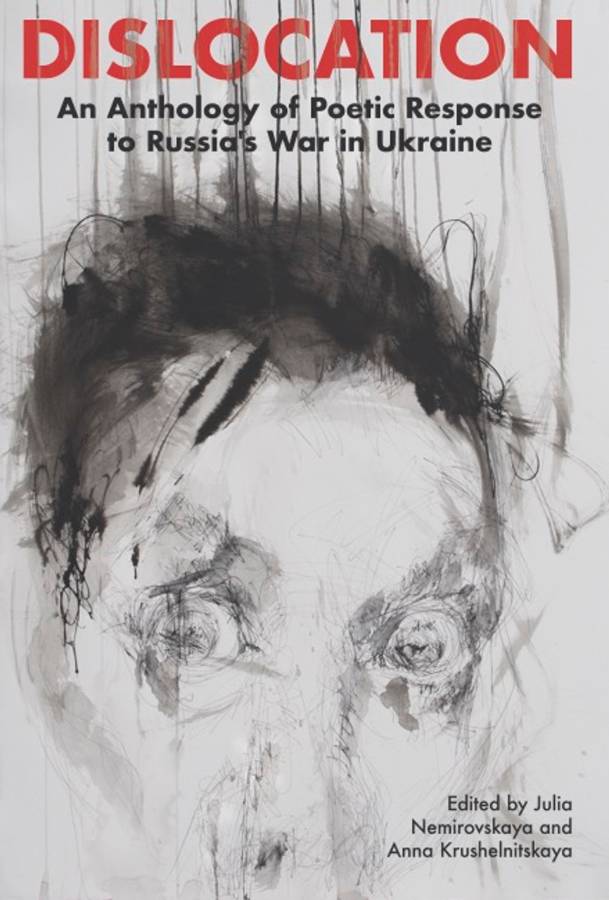

To Yasha

A perfect airfield

Covered with bright August grass

Yet clearly not Pulkovo

What am I doing here

Better not get any further into this

The answer may upset you

May leave you shaken

May break your heart

A pint-size airplane lifts off.

Manufactures an hour and a half of being nowhere.

Being nowhere gives you an opportunity to be something other than nobody

Not a laborer not a performer of duties in neutral gear not a pedantic observer of propriety:

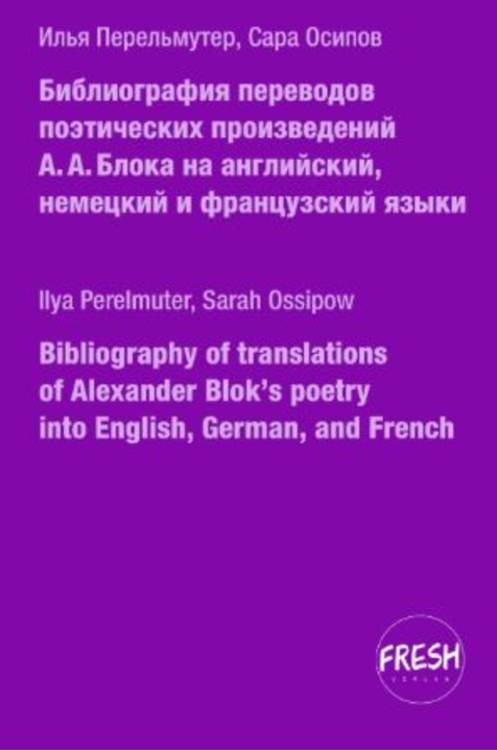

Let’s say to be oneself: a reader of let’s say Turgenev, I.S.

In our cursed times

Reading Turgenev, I.S.

Can appear something disingenuous something imprudent indecent

Reminiscent of what he was like himself:

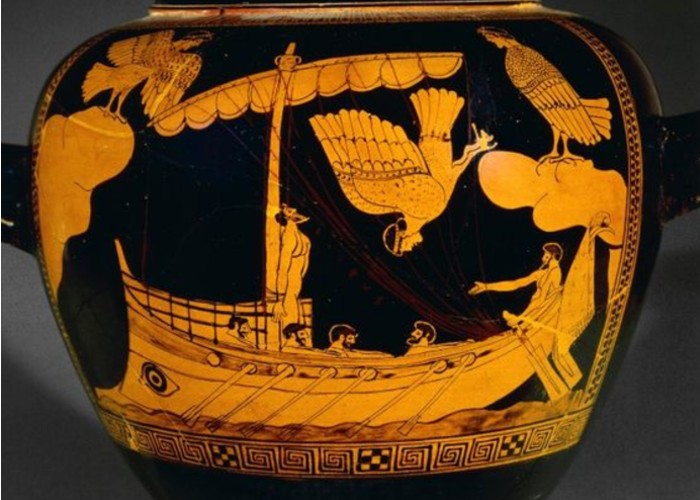

See him in prison

See him in hell

See him in a brothel

See him in the the Tuileries Garden waiting for Zola and scribbling with his stick on gravel:

Jamais encore

Am I a foreigner or what?

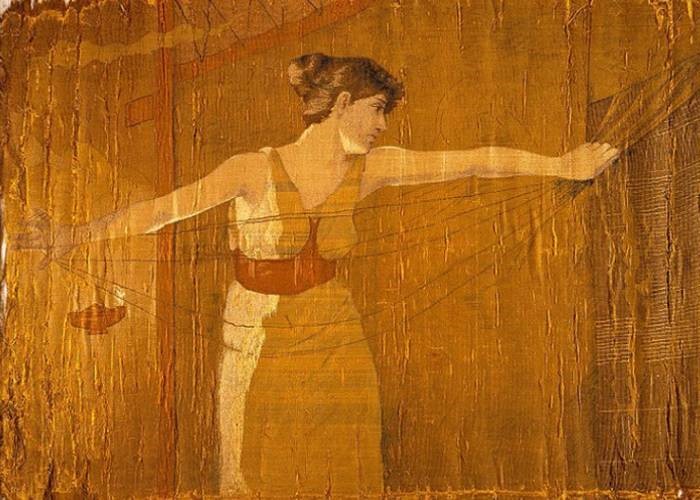

See him in the theater running late overturning a chair in the loge

Everyone hisses hushes

Viardot is ugly

A gypsy a monkey

“Russians are all so boorish”

He leaves the theater

His hands tremble

His lips quiver

The city of PB makes him

sick with its beauty

What am I doing if I’m not at Pulkovo

Who am I if what I’m reading isn’t Turgenev

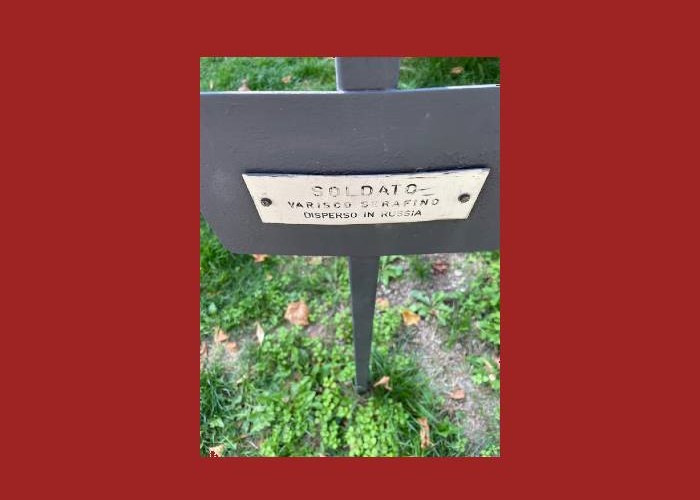

Why do I exist if I’ve left my father’s grave:

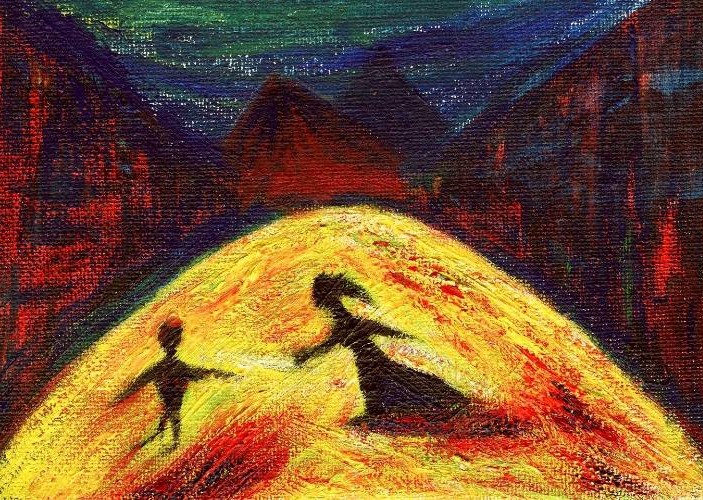

So tenderly/laughably/protectively he pushed my sled in Pulkovo

Down the side of a hillock in fact an old defensive structure

A DFP

Around which a playground has sprung up –

Such is the life of a monument.

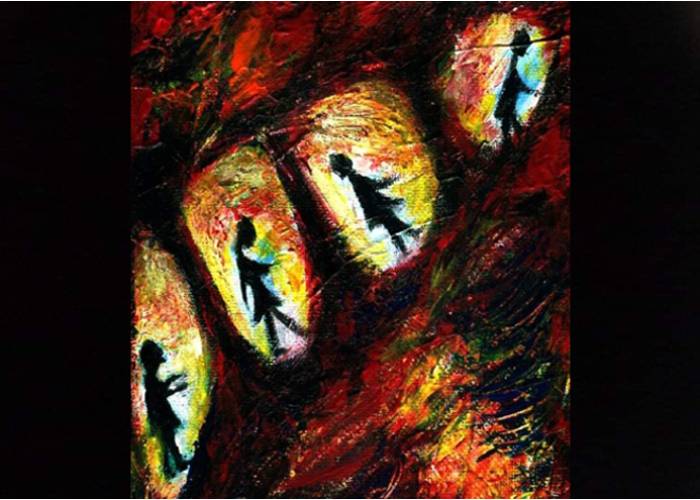

What should a Turgenev monument be like?

Which moment should it commemorate?

Him yelling (in a high-pitched voice – a giant with a high-pitched voice – weird)

At Tolstoy who’s grown weary of his sentimentality?

Him on his knees, weeping in front of Viardot (who probably still gave in to him in a fit of absent-mindedness)?

Him, confined in his family estate for publishing a dirge for Gogol,

Wandering the autumn aspen grove with a red dog?

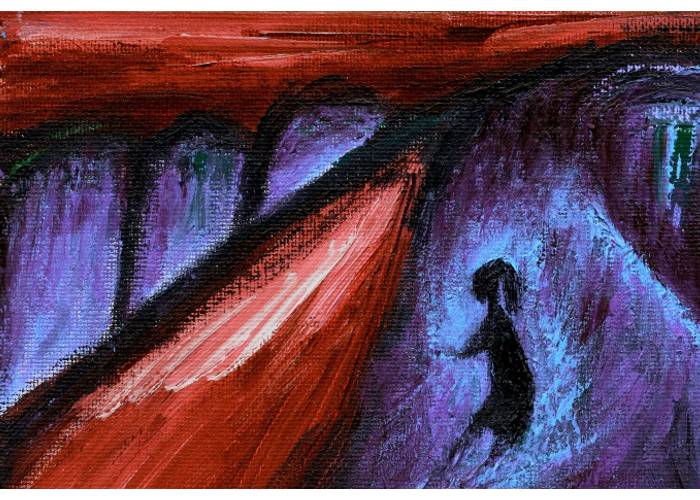

Yes, let this be his monument:

Defiant daring derisive

Free at last

whistling a tune;

The dog finds him an aspen mushroom and grins

And yet, screw all these monuments:

Just the scary beguiling letter-faces of the dead –

You weren’t at your highest (heights) today.

* * *

Пулковская высота

Яше

Отличное лётное поле

Покрытое яркой травой августа

Но явно не Пулково

Что я здесь делаю

Лучше бы не задаваться этим вопросом

Ответ может тебя огорчить

Может тебя потрясти

Может разбить тебе сердце

Самолётец взлетает.

Производит полтора часа пребывания в нигде.

Пребывание в нигде даёт тебе возможность побыть не никем

Не рабочим не исполнителем на нейтральной скорости не соблюдателем категории «прилично»:

Но скажем собой: читателем скажем Тургенева И.С.

В наше проклятое время

Чтение Тургенева И.С.

Может показаться неискренним неблагоразумным неприличным

Несколько напоминающим его самого:

Вот он в заточенье

Вот он в аду

Вот он в борделе

Вот он в саду Тюильри ждёт Золя чертит палкой на гравии:

Jamais encore

Иностранец ли я или кто?

Вот он идёт в театр опаздывает роняет стул в ложе

Все шикают шикают

Виардо безобразна

Цыганка обезьяна

«Русские все такие грубые»

Он выходит из театра

У него губы дрожат

У него руки дрожат

Город ПБ вызывает у него

своей красотой тошноту

Что я делаю если я не в Пулково

Кто я если я читаю не Тургенева

Зачем я есть если я покинула могилу отца:

В Пулково он нежно/смешно/защитно сталкивал мои санки

С горушки которая была собственно защитное сооружение

ДЗОТ

Вокруг которого разрослась детская площадка—

Такова жизнь памятника.

Каков должен быть памятник Тургеневу?

Какой момент нам следует запечатлеть?

Когда Он орет (очень высоким голосом- гигант с высоким голосом- странно)

На уставшего от его чувствительности Толстого?

Когда Он плачет, стоя на коленях, перед Виардо (которая вероятно в минуту рассеянности все же ему дала)?

Когда Он, будучи заточен в своё имение за заплачку по Гоголю,

Бредёт по осеннему осиннику с рыжим псом?

Да — вот этот памятник выберем:

Осмелившийся смелый насмешливый

Наконец свободный

насвистывает;

Пёс обнаруживает для него подосиновик и улыбается

Но на хрен все же все эти памятники:

Только страшные прелестные лица- буквы мертвых—

Сегодня вы были не на (своей) высоте.