That morning, back in 1966, when our dear friends the Vietcong won yet another victory over the American imperialists, the whole class stood at attention under the watchful eye of a Soviet warrior in a poster. The warrior held a red rocket in his right hand, while a tiny American pilot dangled from his left one. In the background, a downed spy plane was falling from the flat-blue sky. The caption said, “Soldiers of peace, be vigilant.” The water dripping from the ceiling had erased the letters A and C in the word “peace.”

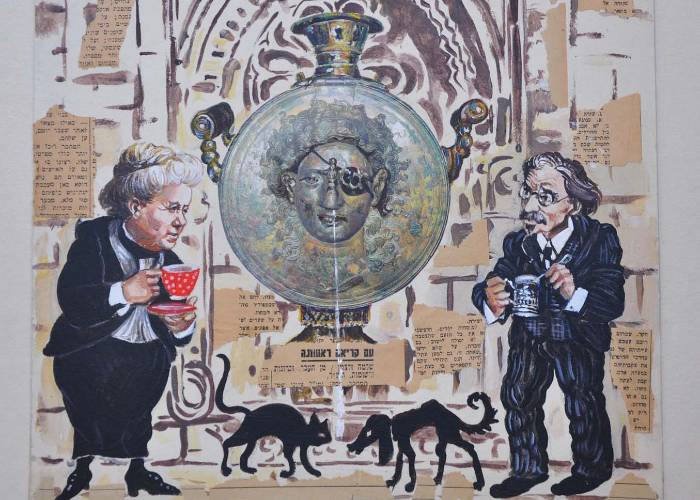

The geography/scientific atheism teacher, Maria Ivanovna Babayaga, marched down the aisle of black-painted double desks, glancing at kids’ faces. She was shaped like a potato, not the sweet American kind, but of the domestic variety with a few longer sprouts for the limbs, and shorter ones for the nose and ears, as well as an ugly knife cut for the mouth and two moist drops for the eyes. She wore a civilian outfit: an olive dress, boots and medals for Valor, Second Class, and for Liberation of Warsaw either from the Nazis or the Poles.

She stopped when she approached Alex, the only Jewish boy in the class. At sixteen, tall, thin, and bookish, he resembled an exclamation point.

“Who read the whole ‘Taras Bulba,’ kids?” she asked the class, giving Alex the evil eye.

They studied Gogol’s long story in Russian literature class. Taras was a Ukrainian hetman—a Cossack warlord—who fought the Poles in the 17th century. This was a tale so viciously anti-Semitic (though classically well written by the hand of a master) that even the Soviet government, far from being Jew-friendly, didn’t allow chapter 4 to be read in high school.

Alex had checked out the unabridged version at the library and offered to read it to his Grandpa at home. Grandpa was seventy, but he still could split a log with an ax in a single blow.

Grandpa refused to listen. He said he was busy. He said he read the book when he was in school. He said that when he was little, he saw an epitaph on a tombstone. This epitaph was a play on the old slogan of the Russian ultra-nationalist organization Black Hundreds, “beat the Jews, save Russia:”

“Here lie Taras and his son Pasha. / They beat the Jews, but did not save Russia.”

“You made it up,” Alex had said.

“Isn’t that what the writers do?” Grandpa had said. “Make up things to advance the truth and to entertain humanity? Regardless, want to help me split some honest logs?”

That night was Hanukkah, the festival of lights. Grandpa lit a menorah in the back of the room.

“It’s supposed to be on the windowsill,” he said. “But it’s not safe there.”

“Afraid of the fire?” Alex asked.

“Afraid of the KGB.”

“I read the whole ‘Taras Bulba,’” Mura Vasilyava, the teacher’s pet mewed now. She had the spine of a cat, and Alex suspected that she could lick her own behind.

“Do you remember how Taras saved that Yankel in chapter 4?” Maria Ivanovna asked her, and returned to watching Alex.

Alex remembered though he said nothing aloud. “There will always be plenty of time to hang the Jew,” Taras said in that chapter, “if it proves necessary; but for to-day give him to me.”

“Yes, I do remember,” Mura replied, displaying her needle teeth, gleaming like in the Grandma’s prized Singer sewing machine.

Alex stood at attention, waiting for the blow to come. “Taras hewed and fought, dealing blows at one attacker after another, but still keeping his eye upon Ostap ahead…”

“That chapter had a great description of the Russian national character,” Maria Ivanovna said.

Alex couldn’t handle the suspense any longer.

“Taras was a Ukrainian, Maria Ivanovna,” Alex said. “He exhibited anti-Socialist behavior. He called the Jews Kikes. And ‘bulba’ is a Ukrainian word for ‘potato.’ Not very romantic.”

“Unlike one specific minority—the rootless cosmopolitans, both Russians and Ukrainians belong to the root nations,” Maria Ivanovna had finally delivered the blow.

“But for this counsel he received a blow on the head with the back of an axe, which made everything dance before his eyes.”

Half of the class laughed. Rimma, the only Jewish girl, one specific minority, gave Alex a thumb up.

“The noble lady rose before him: again there gleamed in his memory her beautiful arms, her eyes, her laughing mouth, her thick dark-chestnut hair, falling in curls upon her shoulders, and the firm, well-rounded limbs of her maiden form.”

Actually, Rimma’s hair was red, so in a pinch she could have ridden in front of the cavalry regiment, her hair flowing in the wind like a red banner. Well, maybe she didn’t mean to support Alex. “Or had the Jew been deceiving him…”

Maria Ivanovna returned to her desk.

Alex could tell that she considered the sole male representative of the specific minority sufficiently humiliated. He wished he could fall through the floor to the gym below and find a big enough bat to dispatch her.

“The terrified Jew set off instantly, at the full speed of his thin, shrunken legs.”

Since he didn’t fall through the floor, he began to hope that the teacher’s chair would collapse under her considerable weight, and she would expose her panties in the process of falling, a sky-blue flannel monstrosity reaching to her knees, according to the boys at the front desk.

“Fall to the earth with a sound of thunder…”

No such luck.

In the story, Taras killed his son Andrii, a turncoat. An enterprising folklorist inserted this line at the book’s margins: “’I’ll kill you with what I’ve sired you with,’ Taras told Andrii and stepped two meters aside.”

Alex listened to the teacher telling the kids why it was beneficial for the small nations of the Caucasian Mountains to become a part of Russia in the 19th century, and thought about Taras’ underlings in the end of the story.

“The Cossacks rowed swiftly on in the narrow double-ruddered boats—rowed stoutly, carefully shunning the sandbars, and cleaving the ranks of the birds, which took wing—rowed, and talked of their hetman.”

The teacher kept talking. The wound of her mouth kept opening and closing. But Alex didn’t listen any longer.

After the bell, he strolled along the hallway, its walls decorated with the portraits of famous Russian writers, until he stopped by the portrait of Gogol, dapper with his long hair and trimmed mustache.

“How come you were an anti-Semitе, Nikolai Vasilievich?”

Gogol barely moved his lips. “Because I was a product of my time.”

“That’s just a cliché. Next thing you’d say you had Jewish friends.”

Gogol didn’t even bat an eyelash. “My estate manager was Jewish. I gave him presents for Easter. His name was Trotsky.”

“Leon Trotsky?”

“David. The help loved him.”

Something moved behind Alex. A reflection of red fire fell on the writer’s face, and he squinted.

“Are you talking to yourself?”

Alex turned around. Rimma.

“No way. Just interrogating Gogol. In Ukrainian.”

“Trying to be funny?”

“Trying? I’m always funny… Would you like to go rowing with me? My Grandpa’s friend has a boat.”

“I’d love to.”

They left holding hands, and Gogol was making faces behind their backs. He probably forgot how to row an honest Russian boat, and was jealous.

An hour later, Alex and Rimma were rowing south-west, away from the coast. The sea was black. The wind howled. Cold rain fell in heavy sheets behind them, like an iron curtain. The waves tossed sea salt into their faces.

They kept rowing toward the place where they hoped they could be treated a bit fairer, rowing even swifter than an average Cossack, as if the ghost of Taras was gaining on them fast.

Soon, the wind calmed down, and the stars appeared, like the lights of a billion menorahs, like no one in heaven was afraid of the KGB.

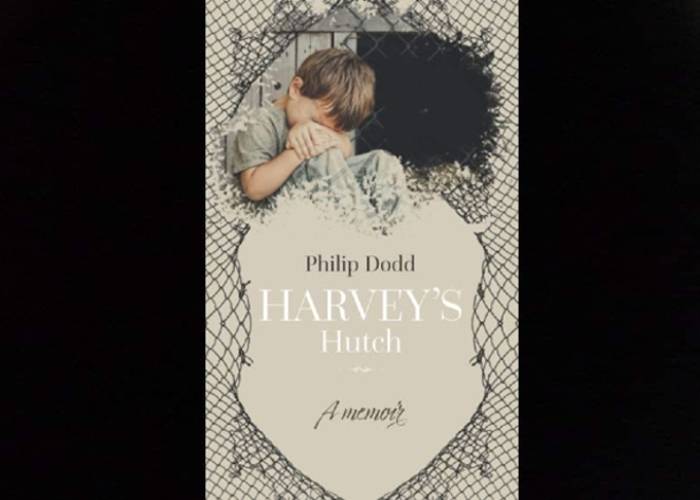

Someone dapper, someone bilingual or even tri-lingual, should write a long story about them, a story that would be read and studied in schools for hundreds of years.