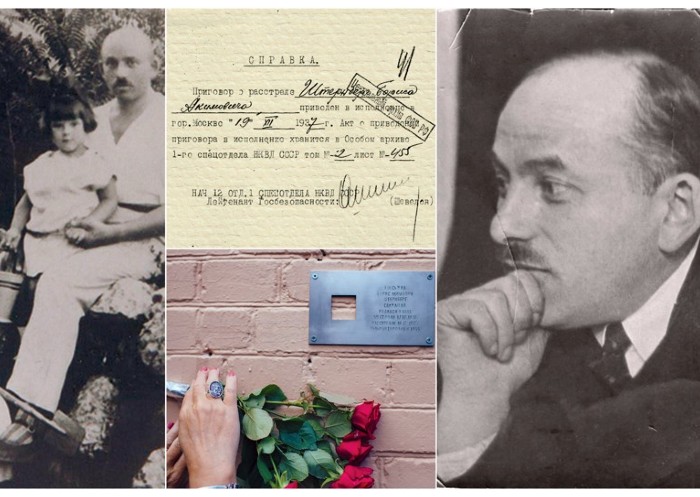

My grandfather was executed in Moscow in 1937 after he had been tortured into signing a false confession of being a British spy, which automatically made him an “enemy of the people”. I saw this photo of him when I was a child, and I always knew that he was innocent. He came to me in a dream one night and told me where to go and what to do to bring him back to life. I went where he had told me. When I finished doing what he had instructed me to do, there he stood in front of me, tall and frail and leathery-skinned. He was significantly taller than anyone else in my family. He was also significantly weaker. When I gently turned him around, I saw a hole in the back of his head. He was afraid of sunlight, and as soon as he stood up in front of me for the first time, he made it as if to hide in the darkest corner, to fall apart into pieces again, to dissolve into nothingness. I held onto him with both my hands, I wouldn’t allow him to become dust. I guided him outside, where tree branches waved, welcoming him after so many years of absence. I found a spot under a tree, maybe an oak, a big tree generous with its shade. I had my grandfather standing there, leaning on the tree, protected from sunlight and occasional passersby. I told him I had to leave him alone for a short while, hopefully no more than a few minutes, and while I am gone, I said, he should stand there, and not attempt to go anywhere, just stand and wait until I come back with my car. You don’t know this world anymore, everything has changed, the world is dangerous. Something moved in his eyes, they filled with liquid, and I interpreted it as a yes. I kept turning back at him as I walked away, to make sure he was still standing, still flesh. My car was parked six blocks away. I ran, my speed the speed of the wind. When I got into the car, I saw that the street in front of me was blocked by traffic. The wait seemed inordinately long, ten or fifteen minutes, until a traffic policeman opened up a side street, and all the honking suddenly stopped, and I followed other cars driving in the wrong direction on a one-way street. I saw the big oak or whatever it was, that tree generous with its shade. My grandfather wasn’t there. I searched everywhere, every tree in the neighborhood, every bush, I knocked on every door. Some doors were shut in my face, some people felt pity for me, and most looked at me blankly when I told them that I’d lost my grandfather. I didn’t tell them I had resurrected him from the dead. Or that he had been tortured and shot by Stalin’s henchmen over eighty years ago. If the great purge and its millions of victims are no more than a tale to most of them, then why would they care about what I say? And of course, I have no proof, except for the story I tell everyone I meet, hoping they have seen the man with a hole in the back of his head, walking like a blind man through the streets of our merciless city.