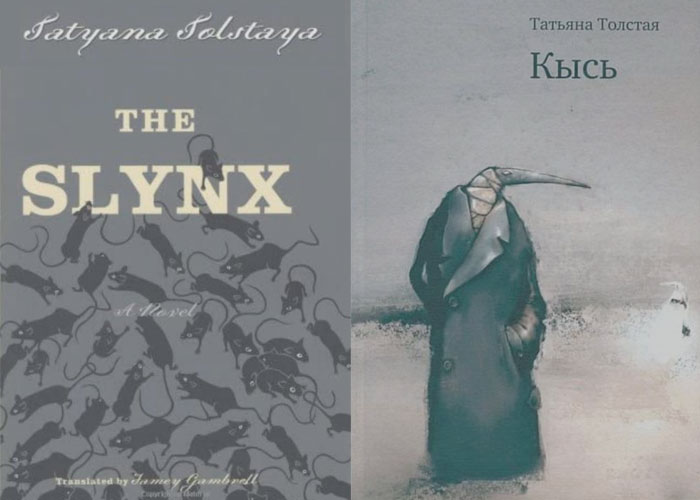

The Slynx by Tatyana Tolstaya

Translated by Jamey Gambrell

Houghton Mifflin, 275 pages, ISBN: 0618124977

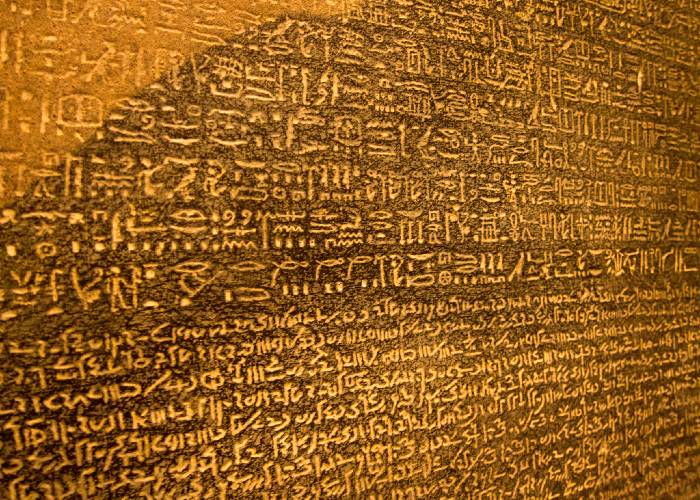

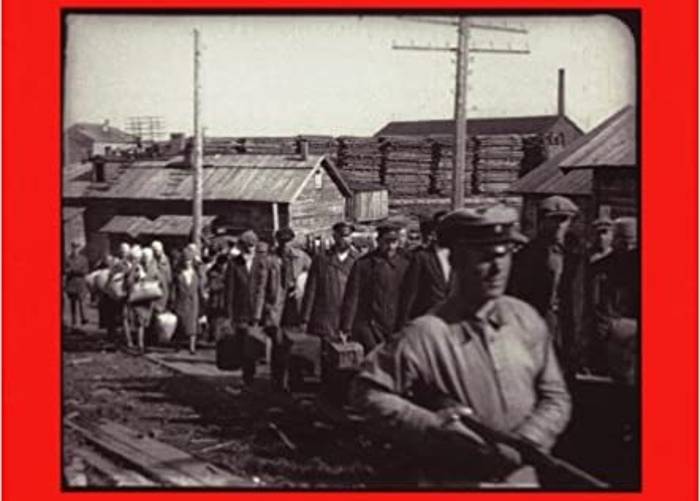

Tatyana Tolstaya’s The Slynx is in some ways similar to Margaret Atwood’s Onyx and Crake. Tolstaya’s novel takes us two hundred years into a post-apocalyptic future, and constructs a dystopia of communal life in a village standing on the ashes of what used to be part of Moscow. Importantly, Tolstaya demonstrates how the meanings of words atrophy given certain cultural conditions—when what prevails is widespread ignorance and complete intellectual impoverishment. In other respects, and with its dark humour in particular, The Slynx veers away from the Atwood mode, approaching the paradoxical ambience of Joseph Heller instead. One might look to Catch-22 for a satirical approximation, although The Slynx is a different breed: Tolstaya is Russian, which means that she employs some traditional elements of storytelling. Also, she capitalizes on her insider’s knowledge of the national psyche, concerning herself with the accumulated rot of a particular social and political order—that of Russia’s Communist era. Her adroit satire isn’t parochial, however, and her message—that text, the written word, no matter how rich, will remain inaccessible if the intellect isn’t primed by a culture that is itself sufficiently developed—is universal.

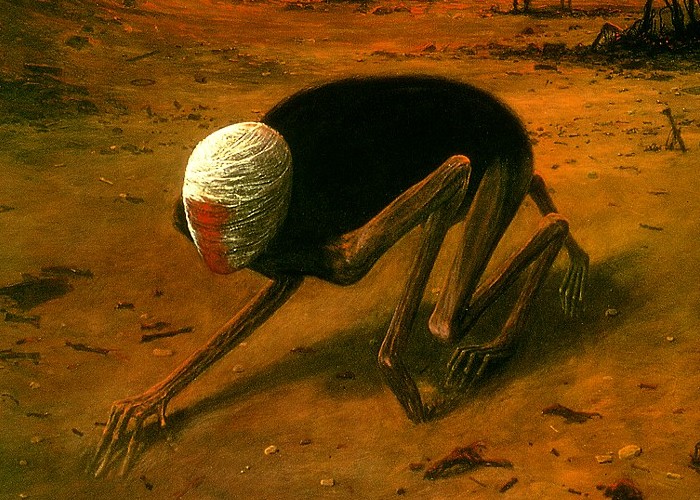

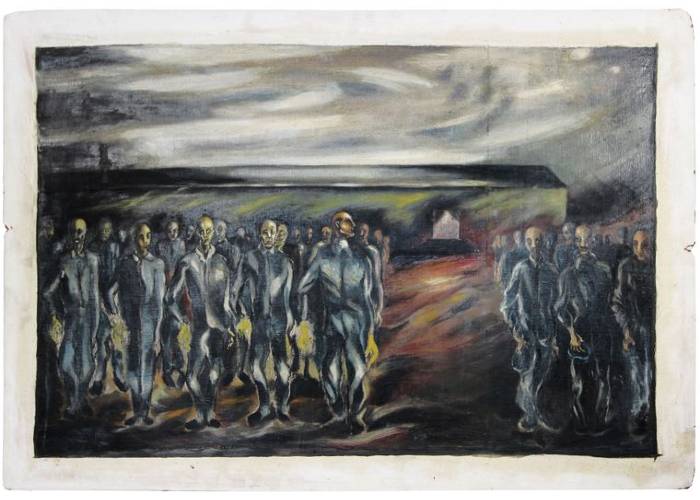

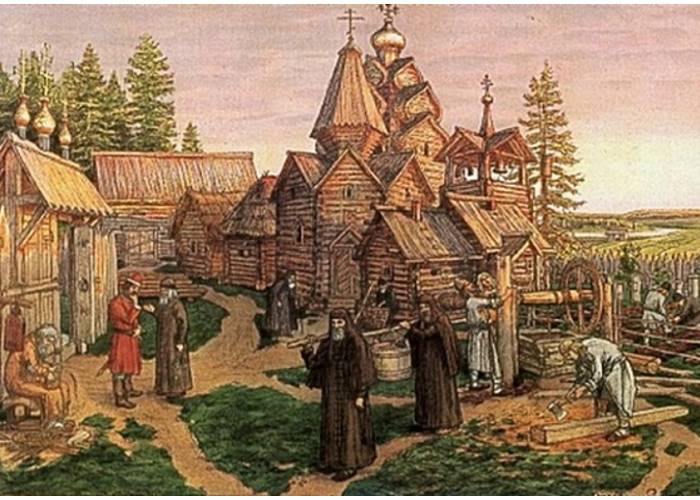

“The Blast” flattens everything, but 200 years later, a rudimentary-type communal life is re-established. A microcosm and an extreme parody of its former self, this small community of Soviet-ish citizens exists in utter misery. Mice are the people’s dietary mainstay, in addition to worms, and a limited number of hardy, easily grown vegetables. The inhabitants live in tiny huts or “Isbas”, outfitted with wood-burning stoves but no other conveniences. They come close to freezing to death in the winter months. In addition, many suffer the “consequences” of radiation in the form of unsightly physical mutations. And yet, even this bundle of sorry have-not’s is held together, fearful and servile, by rules and ever accruing dictates, which are the misconstrued and hilariously misapplied vestiges of the Communist regime and its endless red tape. Little has changed in other words. It’s the same old crap, but now it operates at higher levels of absurdity.

The “governmental approach,” as well as every detail of the mind-numbing routine of daily life in the village, is described by the protagonist, Benedict, without the slightest irony. His manner of life and the pitiless ways of those in positions of authority make sense to Benedict, as they do to every other ignorant member of his community because not one of them has ever known anything different. Besides, Benedict’s own uninformed, convoluted reasoning reflects to perfection the cultural torpor of this small society.

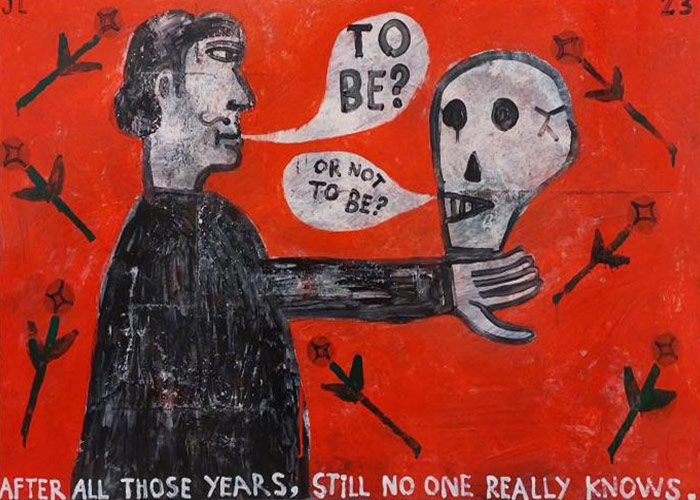

Archetypally, Benedict is the old Ivan, the standard issue hero of Russian folklore; he is uncouth, untutored, but a happy-go-lucky “muzhik”, who carries on no matter which misfortune befalls him. But unlike the Ivan of old, he has undefined longings; from time to time cognizance overtakes him, and he suffers from a kind of existential angst, an involuntary awareness that his life is crushingly empty—that he’s unfulfilled.

Once married to the beautiful Olenka, daughter of the dreaded “Head Saniturion” (the play on “sanitarium” and ancient Rome’s “centurion” is just one example of how words have become mangled and original meanings lost or perverted), Benedict discovers that while most inhabitants of the village are dirt poor, there are some who possess luxuries he never imagined. One of these luxuries is a library filled with “oldenprint” (pre-blast) books and magazines, precisely that which is forbidden to the general populace.

The library and its contents become an obsession for Benedict. He consumes every book and journal, but while he reads ceaselessly, he reads indiscriminately. He doesn’t discern that some books are more important than others—that some are literary masterpieces and others shlock, or that some of the publications are how-to manuals while others address issues of philosophical, moral and political importance. Having read everything, he decides to organize the library, arranging material in accordance with his own methodology: “….Popescu, Popka-the-Fool—Paint It Yourself, Popov, another Popov, Poptsov, The Iliad, Electric Current, he’d read it, Gone With the Wind, Russo-Japanese Polytechnical Dictionary, Sartakov, Sartre, Sholokhov: Humanistic Aspects, Sophocles, Sorting Consumer Refuse, Stockard, Manufacture of Stockings and Socks,…he’d read that one, that one and that one….”

Trying to impress the village sage, Nikita Ivanich, Benedict boasts that he has been reading about Freedom, or more precisely about “how to make freedom.” He recites from “Plaiting and Knitting Jackets”: “When knitting the armhole we cast on two extra loops for freedom of movement. We slip them on the right needle, taking care not to tighten them excessively.” To this, another member of the community, the astute Lev Lvovich, responds by remarking: “We’ve always known how to tighten things excessively around here.” The humour is burlesque, but the exchange also demonstrates Benedict’s complete inability to extract meaningful ideas from books. They are comfort to him, and he prizes them above everything and anyone else because he intuits their beauty, and because they enable him to escape the tediousness of daily life, but despite his addiction to reading, books aren’t a source of enlightenment. On the contrary—and what amounts to a strange twist—they become the instrument of his corruption.

Initially resistant to the idea, Benedict nevertheless allows himself to be convinced by his father-in-law, the ambitious Kudeyar Kudeyarich, that for the sake of “preserving art and culture” he must take on the responsibilities of a saniturion and help him “treat” the ignorant and spiritually-bereft members of the community lest they destroy whatever books are being hidden in their possession. The crafty Kudeyar Kudeyarich is deceiving Benedict, merely dangling the prospect of more books before him, but Benedict is vulnerable where books are concerned. Not only is he desperate for more, he genuinely deplores the thought that what he loves with such intensity may be unwittingly damaged by those who wouldn’t know better. And so, he becomes cruel, a terror onto others in his effort to “save ” books, unsparing of any man or woman he thinks may be keeping one. Eventually, the same motivation leads him to the conclusion that for the sake of art he must help Kudeyar Kudeyarich “overthrow the government.”

Tolstaya’s satire is at its acerbic peak when, right after murdering Fyodor Kuzmich, the head “Murza”, the two dullards sit down to compose barely literate decrees describing the rights of the people. Power hungry and ruthless, but also primitive in his thinking, Benedict’s father-in-law is even less interested in the people’s wellbeing than the previous head of government, and Benedict himself is untroubled by the fact that the change in authority is a step backward for the ordinary folk. He is long past caring about social justice. Any means are justified as long his fanatical aim of saving “literature” and amassing books for himself is realized.

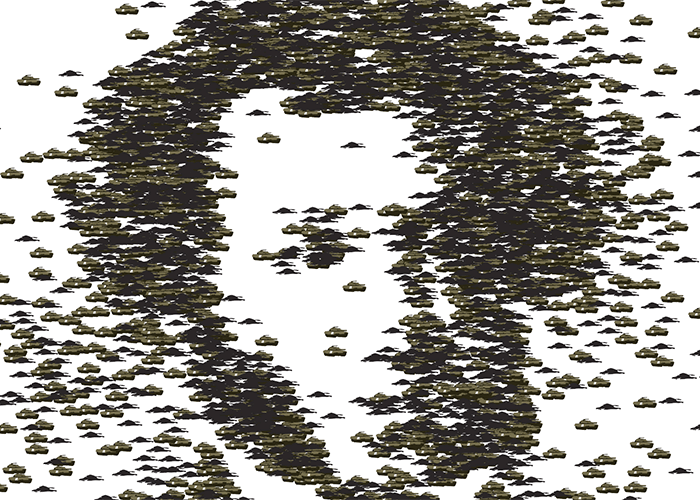

Thus, we witness Benedict’s gradual transformation into an anti-hero. It is no coincidence that the “consequence” he had been born with was a small tail. He resembles a dog—limited in terms of what he can learn and comprehend, and despite an inherently good disposition, malleable, and capable of turning vicious. He is only as good as his training—only as good as the circumstances in which he is socialized. The same rule, Tolstaya seems to be suggesting, applies to language and thought. A cultural field must be properly tended or else what grows isn’t worth harvesting. In her novel, the dark age is what transpires in the future, but her Russia represents a mutation which has already occurred. Nikita Ivanich, whose voice is the only voice that hints at understanding, declares knowingly, “Why is it that everything keeps mutating, everything? People, well, all right, but the language, concepts, meaning! Huh? Russia! Everything gets twisted up in knots.”

The Slynx is a profound work. It is well served by Jamey Gambrell’s exceptionally fine translation.