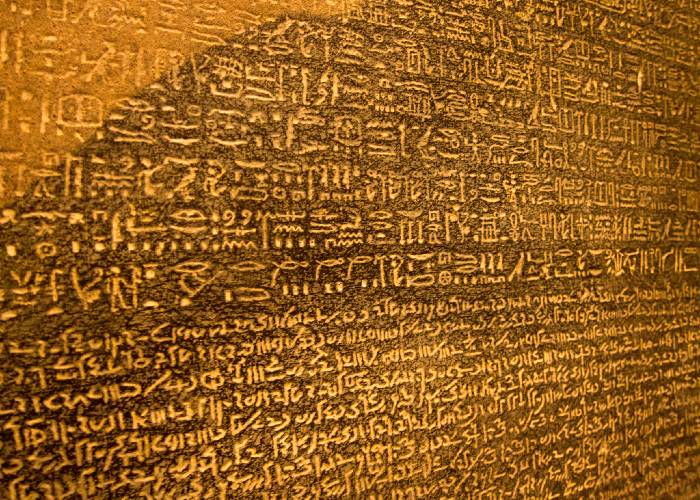

Growing up, I’d always felt averse to politics and it took me years to realize that my difficulty had a lot to do with the role of Soviet history in my family’s history. The shift came while I was at the CalArts School of Critical Studies, studying writing and philosophy, and where I first read Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Adventures of the Dialectic (1955) – a book that, in his words, articulates “a philosophy of both history and spirit.” In this book, I discovered not only a language for history that incorporated its spirit too, but also the realization that I had to come to terms with how immense historical forces affect the lives of generally inconsequential people – sometimes even shaping the very circumstances by which we come to exist. And that, in our case, there was no way to fathom these influences without knowing something about the Soviet Union.

I’ll explain. My parents were born on opposite sides of the Black Sea – my father in Tbilisi, Georgia, my mother in Kishinev, Moldova – and they met in 1967 at a summer resort not far from the Ukrainian port town of Odessa. They were both musicians and both raised in Jewish homes, so that, very quickly, a summer flirtation turned into a potential match. But it wasn’t love that brought them together. It was Soviet survival.

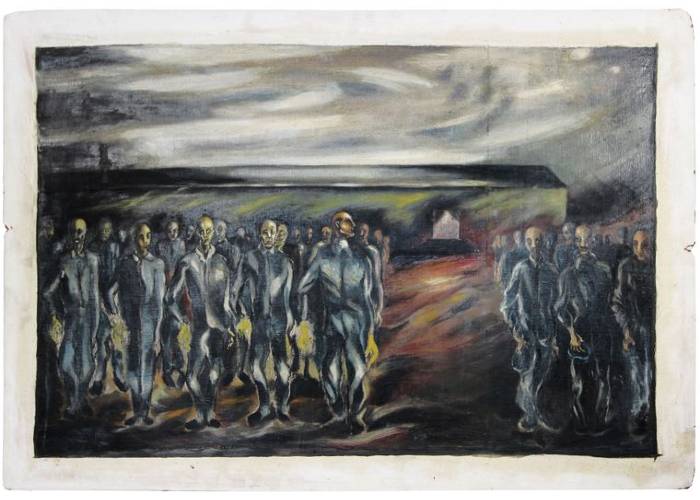

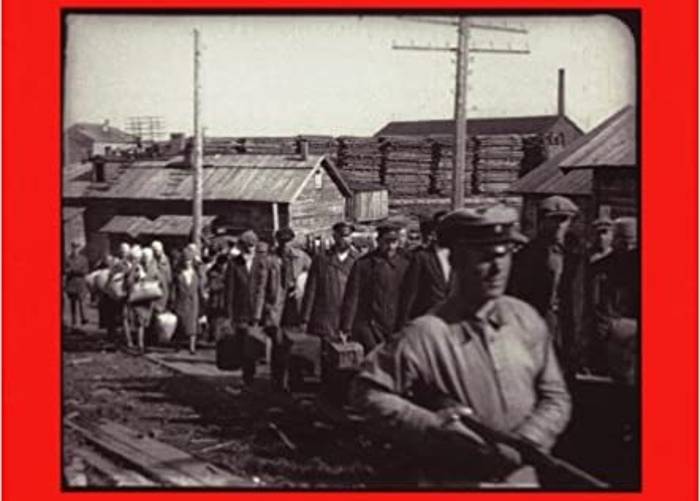

My father’s father, a Soviet businessman who’d sat in a prison camp for eight years after an informant triggered an audit of his work, found out that my mother’s father, a tailor who’d fought in the Red Army in the Second World War, was being transferred to Moscow. The tailor, who’d been on the front and made alive it all the way to Berlin, had sewn suits for Leonid Brezhnev, who was in 1950 made Party First Secretary of the Communist Party of Moldova, and who made a man named Nikolai Shchelokov Second Secretary and First Deputy Premier as well as a member in the Supreme Soviet. Shchelokov made my grandfather his personal tailor. In 1966, two years after Brezhnev became the leader of the USSR, Shchelokov became Minister of Public Order or, as the position was known a couple of years later, Minister of Internal Affairs – which is to say, the Soviet Chief of Police. A year after going to Moscow, Shchelokov brought over his Jewish tailor.

As my father later explained to me, Shchelokov was interested in more than well-sewn suits. He also needed a middleman to convey bribes from different ethnic groups. This was long after the Stalin era, when any arrest ended with either immediate execution or twenty years of hard labor in Siberia. In Brezhnev’s Russia, the fates of non-political, criminal prisoners could be lightened with money or valuables. Since the concept of pidyon shvuyim, or bringing about the release of fellow Jews imprisoned unjustly by authorities, was deeply ingrained in the Jewish tradition, the Soviet authorities could count on friends and family trying to help anyone who was arrested. And since almost anything you did in the Soviet Union was prosecutable, this meant there was a constant need for contacts to bring bribes to the highest officials.

The thing was that my grandfather the tailor wanted nothing other than to sew suits, and this put him in a bind, because, when the leader of the USSR and its Chief of Police tell you that you’re moving to Moscow to be their “tailor,” you can’t quite turn down their offer. And here is where my businessman grandfather enters the story. Suddenly there was a chance of passing the dirty work off to someone else, in this case the groom’s father, who was only too happy to take on the burden, since there was no better way of staying out of jail than going into business with the police.

I don’t know how exactly all this came to be known between my two grandfathers, but once the two sides saw the advantages of the match, the marriage was arranged, especially since the connections also made it possible for my parents to enroll in the Gnessin State Musical College. And so in this way, two people who were so mismatched that it’s hard to imagine them ever being together, got locked into nearly twenty years of a shared life in which they had a first child, emigrated to Israel, had a second child, and emigrated to the United States – only to have the family break up.

I was six-and-a-half when our family fell apart. I was sent back to Israel with my mother, whose parents had died before we’d moved to America, and so we moved in with my father’s parents, living in an outlying part of Jaffa, while my father and older sister stayed behind in Los Angeles. Two years later I went to live with my father in America, growing up in immigrant ethnic neighborhoods and inner city schools, until I began to be bused out to high school in Van Nuys, and made it into college on the West Side at UCLA – where I majored in mathematics but spent most of my time studying literature and art.

It’s hard to describe – even in Merleau-Ponty’s terms – the historical and spiritual distances that separated the Soviet Union of my family’s past from the West LA reality in which I was then living. Yet it was there, at UCLA, that I experienced the embarrassment of having no historical consciousness. It was a spring afternoon in my freshman year, and I’d just gone up to a group of students, one of whom I knew, when one of the others asked me, in a knowing tone, whether I was a radical. I asked him what that meant. “A radical,” he said, “you know, a communist.” I smiled. “No,” I said, and, resentful of the question, added , “I happen to be a capitalist.” I didn’t really know what that meant, either, so I added, “My parents are from the Soviet Union.” He asked me where they’d come from, and when I said my father was from Georgia, he said, “Well, it’s not like we’re Stalinists.” Everyone in the group laughed – and, seeing as I was the butt of a joke I didn’t even understand, I laughed along too. I also realized that I was missing some crucial context about my own family’s past.

Merleau-Ponty’s Adventures provided me the context I was missing in a language that spoke not only to my mind but also to my heart. His own writing of that book led him to reconsider everything he thought he knew – to rethink his convictions and beliefs – but, for me, it had another function. It made me aware of my past as a historical subject. It also helped me understand the degree to which – without anyone in our family having been a political prisoner or any other kind of public hero or figure – all of Soviet reality had determined the contours of our family’s history, including my own existence, and the degree to which an exodus from that reality led to its eventual disintegration.

A few years ago, as I was speaking to my mother, who also lives in Jerusalem, she told me she had watched a documentary on Russian television about Schelokov and his corruption. Suddenly, in the middle of the show, the narrator noted that Schelokov’s ministry had nine apartments in the center of Moscow under his control, each of which was assigned to his close relatives and friends – including, she heard the voice on the television say, “his tailor’s daughter, whose family later left for Israel.” Here she was, sitting in her own apartment in Jerusalem, forty years after leaving the USSR, nearly twenty years after the Soviet Union had collapsed, and, on television, they were still talking about the family that lived in a ministry apartment.

Our family benefitted from government contacts, to be sure, but mostly to survive. And this mode of survival wasn’t really sustainable in the long term, especially when new leadership came into power. It’s actually lucky that my parents, sister, and both sets of grandparents left the USSR in 1979 and 1980. Three years later, in 1982, Brezhnev died, and two years later, in 1984, Schelokov was put under investigation for corruption. He allegedly shot himself in order to avoid arrest. But did he really shoot himself? Who knows. The only thing we know for sure is that he’s dead.

Understanding all this took years of speaking to family about our collective past and studying a little bit of Soviet history. I wasn’t planning on becoming a political historian, but I did need to become aware – not only of the world in which I lived, but also the past from which this world emerged. And the period when I developed my historical consciousness made me increasingly aware of how quickly our realities change, and how political developments, like natural disasters and pandemics, can quickly change the course of our daily lives.

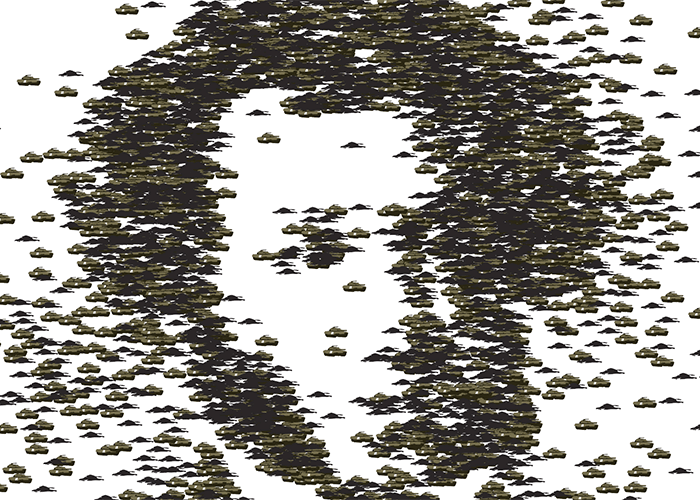

It was during this period in my life that I also started reading news every day – beginning to develop what Thomas Bernhard calls the newspaper disease. Today, I’m constantly reading news and following political developments across the world. By subjecting myself to the newspaper disease, I try to engender antibodies that remind me, over and over, of the degree to which we have to stake out our own territory within history – and to give voice to the spirit of what makes us human. And I don’t just mean culture or the arts. I mean everything about our social existence that keeps us bound to the fact that, long after regimes collapse, we still share this reality with others.